Beauty products aren’t usually the first applications that come to mind when discussing graphene or any other research and development (R&D) as I learned when teaching a course a few years ago. But research and development in that field are imperative as every company is scrambling for a short-lived competitive advantage for a truly new products or a perceived competitive advantage in a field where a lot of products are pretty much the same.

This March 15, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily describes graphene as a potential hair dye,

Graphene, a naturally black material, could provide a new strategy for dyeing hair in difficult-to-create dark shades. And because it’s a conductive material, hair dyed with graphene might also be less prone to staticky flyaways. Now, researchers have put it to the test. In an article published March 15 [2018] in the journal Chem, they used sheets of graphene to make a dye that adheres to the surface of hair, forming a coating that is resistant to at least 30 washes without the need for chemicals that open up and damage the hair cuticle.

Courtesy: Northwestern University

A March 15, 2018 Cell Press news release on EurekAlert, which originated the news item, fills in more the of the story,

Most permanent hair dyes used today are harmful to hair. “Your hair is covered in these cuticle scales like the scales of a fish, and people have to use ammonia or organic amines to lift the scales and allow dye molecules to get inside a lot quicker,” says senior author Jiaxing Huang, a materials scientist at Northwestern University. But lifting the cuticle makes the strands of the hair more brittle, and the damage is only exacerbated by the hydrogen peroxide that is used to trigger the reaction that synthesizes the dye once the pigment molecules are inside the hair.

These problems could theoretically be solved by a dye that coats rather than penetrates the hair. “However, the obvious problem of coating-based dyes is that they tend to wash out very easily,” says Huang. But when he and his team coated samples of human hair with a solution of graphene sheets, they were able to turn platinum blond hair black and keep it that way for at least 30 washes–the number necessary for a hair dye to be considered “permanent.”

This effectiveness has to do with the structure of graphene: it’s made of up thin, flexible sheets that can adapt to uneven surfaces. “Imagine a piece of paper. A business card is very rigid and doesn’t flex by itself. But if you take a much bigger sheet of newspaper–if you still can find one nowadays–it can bend easily. This makes graphene sheets a good coating material,” he says. And once the coating is formed, the graphene sheets are particularly good at keeping out water during washes, which keeps the water from eroding both the graphene and the polymer binder that the team also added to the dye solution to help with adhesion.

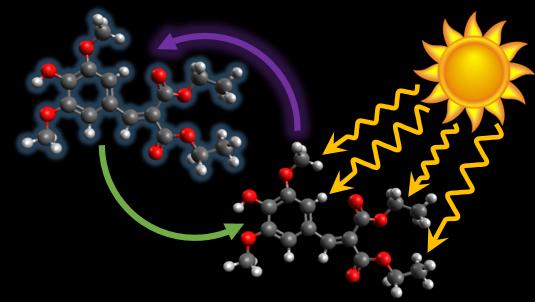

The graphene dye has additional advantages. Each coated hair is like a little wire in that it is able to conduct heat and electricity. This means that it’s easy for graphene-dyed hair to dissipate static electricity, eliminating the problem of flyaways on dry winter days. The graphene flakes are large enough that they won’t absorb through the skin like other dye molecules. And although graphene is typically black, its precursor, graphene oxide, is light brown. But the color of graphene oxide can be gradually darkened with heat or chemical reactions, meaning that this dye could be used for a variety of shades or even for an ombre effect.

What Huang thinks is particularly striking about this application of graphene is that it takes advantage of graphene’s most obvious property. “In many potential graphene applications, the black color of graphene is somewhat undesirable and something of a sore point,” he says. Here, though, it’s applied to a field where creating dark colors has historically been a problem.

The graphene used for hair dye also doesn’t need to be of the same high quality as it does for other applications. “For hair dye, the most important property is graphene being black. You can have graphene that is too lousy for higher-end electronic applications, but it’s perfectly okay for this. So I think this application can leverage the current graphene product as is, and that’s why I think that this could happen a lot sooner than many of the other proposed applications,” he says.

Making it happen is his next goal. He hopes to get funding to continue the research and make these dyes a reality for the people whose lives they would improve. “This is an idea that was inspired by curiosity. It was very fun to do, but it didn’t sound very big and noble when we started working on it,” he says. “But after we deep-dived into studying hair dyes, we realized that, wow, this is actually not at all a small problem. And it’s one that graphene could really help to solve.”

Northwestern University’s Amanda Morris also wrote a March 15, 2018 news release (it’s repetitive but there are some interesting new details; Note: Links have been removed),

It’s an issue that has plagued the beauty industry for more than a century: Dying hair too often can irreparably damage your silky strands.

Now a Northwestern University team has used materials science to solve this age-old problem. The team has leveraged super material graphene to develop a new hair dye that is less harmful [emphasis mine], non-damaging and lasts through many washes without fading. Graphene’s conductive nature also opens up new opportunities for hair, such as turning it into in situ electrodes or integrating it with wearable electronic devices.

…

Dying hair might seem simple and ordinary, but it’s actually a sophisticated chemical process. Called the cuticle, the outermost layer of a hair is made of cells that overlap in a scale-like pattern. Commercial dyes work by using harsh chemicals, such as ammonia and bleach, to first pry open the cuticle scales to allow colorant molecules inside and then trigger a reaction inside the hair to produce more color. Not only does this process cause hair to become more fragile, some of the small molecules are also quite toxic.

Huang and his team bypassed harmful chemicals altogether by leveraging the natural geometry of graphene sheets. While current hair dyes use a cocktail of small molecules that work by chemically altering the hair, graphene sheets are soft and flexible, so they wrap around each hair for an even coat. Huang’s ink formula also incorporates edible, non-toxic polymer binders to ensure that the graphene sticks — and lasts through at least 30 washes, which is the commercial requirement for permanent hair dye. An added bonus: graphene is anti-static, so it keeps winter-weather flyaways to a minimum.

“It’s similar to the difference between a wet paper towel and a tennis ball,” Huang explained, comparing the geometry of graphene to that of other black pigment particles, such as carbon black or iron oxide, which can only be used in temporary hair dyes. “The paper towel is going to wrap and stick much better. The ball-like particles are much more easily removed with shampoo.”

This geometry also contributes to why graphene is a safer alternative. Whereas small molecules can easily be inhaled or pass through the skin barrier, graphene is too big to enter the body. “Compared to those small molecules used in current hair dyes, graphene flakes are humongous,” said Huang, who is a member of Northwestern’s International Institute of Nanotechnology.

Ever since graphene — the two-dimensional network of carbon atoms — burst onto the science scene in 2004, the possibilities for the promising material have seemed nearly endless. With its ultra-strong and lightweight structure, graphene has potential for many applications in high-performance electronics, high-strength materials and energy devices. But development of those applications often require graphene materials to be as structurally perfect as possible in order to achieve extraordinary electrical, mechanical or thermal properties.

The most important graphene property for Huang’s hair dye, however, is simply its color: black. So Huang’s team used graphene oxide, an imperfect version of graphene that is a cheaper, more available oxidized derivative.

“Our hair dye solves a real-world problem without relying on very high-quality graphene, which is not easy to make,” Huang said. “Obviously more work needs to be done, but I feel optimistic about this application.”

Still, future versions of the dye could someday potentially leverage graphene’s notable properties, including its highly conductive nature.

“People could apply this dye to make hair conductive on the surface,” Huang said. “It could then be integrated with wearable electronics or become a conductive probe. We are only limited by our imagination.”

So far, Huang has developed graphene-based hair dyes in multiple shades of brown and black. Next, he plans to experiment with more colors.

Interestingly, the tiny note of caution”less harmful” doesn’t appear in the Cell Press news release. Never fear, Dr. Andrew Maynard (Director Risk Innovation Lab at Arizona State University) has written a March 20, 2018 essay on The Conversation suggesting a little further investigation (Note: Links have been removed),

Northwestern University’s press release proudly announced, “Graphene finds new application as nontoxic, anti-static hair dye.” The announcement spawned headlines like “Enough with the toxic hair dyes. We could use graphene instead,” and “’Miracle material’ graphene used to create the ultimate hair dye.”

From these headlines, you might be forgiven for getting the idea that the safety of graphene-based hair dyes is a done deal. Yet having studied the potential health and environmental impacts of engineered nanomaterials for more years than I care to remember, I find such overly optimistic pronouncements worrying – especially when they’re not backed up by clear evidence.

Tiny materials, potentially bigger problems

Engineered nanomaterials like graphene and graphene oxide (the particular form used in the dye experiments) aren’t necessarily harmful. But nanomaterials can behave in unusual ways that depend on particle size, shape, chemistry and application. Because of this, researchers have long been cautious about giving them a clean bill of health without first testing them extensively. And while a large body of research to date doesn’t indicate graphene is particularly dangerous, neither does it suggest it’s completely safe.

A quick search of scientific papers over the past few years shows that, since 2004, over 2,000 studies have been published that mention graphene toxicity; nearly 500 were published in 2017 alone.

This growing body of research suggests that if graphene gets into your body or the environment in sufficient quantities, it could cause harm. A 2016 review, for instance, indicated that graphene oxide particles could result in lung damage at high doses (equivalent to around 0.7 grams of inhaled material). Another review published in 2017 suggested that these materials could affect the biology of some plants and algae, as well as invertebrates and vertebrates toward the lower end of the ecological pyramid. The authors of the 2017 study concluded that research “unequivocally confirms that graphene in any of its numerous forms and derivatives must be approached as a potentially hazardous material.”

These studies need to be approached with care, as the precise risks of graphene exposure will depend on how the material is used, how exposure occurs and how much of it is encountered. Yet there’s sufficient evidence to suggest that this substance should be used with caution – especially where there’s a high chance of exposure or that it could be released into the environment.

Unfortunately, graphene-based hair dyes tick both of these boxes. Used in this way, the substance is potentially inhalable (especially with spray-on products) and ingestible through careless use. It’s also almost guaranteed that excess graphene-containing dye will wash down the drain and into the environment.

…

Undermining other efforts?

I was alerted to just how counterproductive such headlines can be by my colleague Tim Harper, founder of G2O Water Technologies – a company that uses graphene oxide-coated membranes to treat wastewater. Like many companies in this area, G2O has been working to use graphene responsibly by minimizing the amount of graphene that ends up released to the environment.

Yet as Tim pointed out to me, if people are led to believe “that bunging a few grams of graphene down the drain every time you dye your hair is OK, this invalidates all the work we are doing making sure the few nanograms of graphene on our membranes stay put.” Many companies that use nanomaterials are trying to do the right thing, but it’s hard to justify the time and expense of being responsible when someone else’s more cavalier actions undercut your efforts.

…

Overpromising results and overlooking risk

This is where researchers and their institutions need to move beyond an “economy of promises” that spurs on hyperbole and discourages caution, and think more critically about how their statements may ultimately undermine responsible and beneficial development of a technology. They may even want to consider using guidelines, such as the Principles for Responsible Innovation developed by the organization Society Inside, for instance, to guide what they do and say.

…

If you have time, I encourage you to read Andrew’s piece in its entirety.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Multifunctional Graphene Hair Dye by Chong Luo, Lingye Zhou, Kevin Chiou, and Jiaxing Huang. Chem DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chempr.2018.02.02 Publication stage: In Press Corrected Proof

This paper appears to be open access.

*Two paragraphs (repetitions) were deleted from the excerpt of Dr. Andrew Maynard’s essay on August 14, 2018