The EU-funded Human Brain Project (HBP) comes to an end in September and celebrates its successful conclusion today with a scientific symposium at Forschungszentrum Jülich (FZJ). The HBP was one of the first flagship projects and, with 155 cooperating institutions from 19 countries and a total budget of 607 million euros, one of the largest research projects in Europe. Forschungszentrum Jülich, with its world-leading brain research institute and the Jülich Supercomputing Centre, played an important role in the ten-year project.

“Understanding the complexity of the human brain and explaining its functionality are major challenges of brain research today”, says Astrid Lambrecht, Chair of the Board of Directors of Forschungszentrum Jülich. “The instruments of brain research have developed considerably in the last ten years. The Human Brain Project has been instrumental in driving this development – and not only gained new insights for brain research, but also provided important impulses for information technologies.”

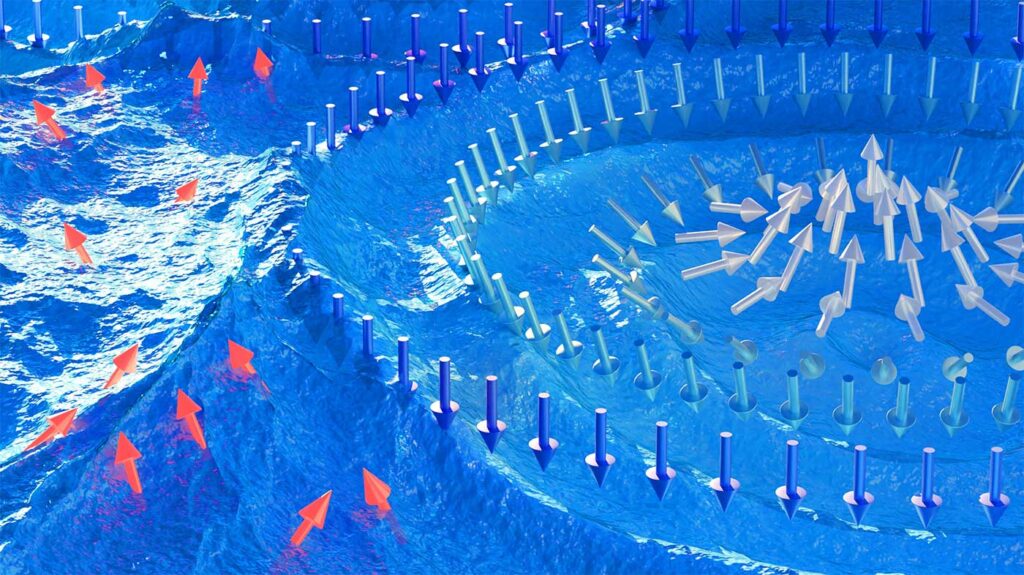

HBP researchers have employed highly advanced methods from computing, neuroinformatics and artificial intelligence in a truly integrative approach to understanding the brain as a multi-level system. The project has contributed to a deeper understanding of the complex structure and function of the brain and enabled novel applications in medicine and technological advances.

Among the project’s highlight achievements are a three-dimensional, digital atlas of the human brain with unprecedented detail, personalised virtual models of patient brains with conditions like epilepsy and Parkinson’s, breakthroughs in the field of artificial intelligence, and an open digital research infrastructure – EBRAINS – that will remain an invaluable resource for the entire neuroscience community beyond the end of the HBP.

Researchers at the HBP have presented scientific results in over 3000 publications, as well as advanced medical and technical applications and over 160 freely accessible digital tools for neuroscience research.

“The Human Brain Project has a pioneering role for digital brain research with a unique interdisciplinary approach at the interface of neuroscience, computing and technology,” says Katrin Amunts, Director of the HBP and of the Institute for Neuroscience and Medicine at FZJ. “EBRAINS will continue to power this new way of investigating the brain and foster developments in brain medicine.”

“The impact of what you achieved in digital science goes beyond the neuroscientific community”, said Gustav Kalbe, CNECT, Acting Director of Digital Excellence and Science Infrastructures at the European Commission during the opening of the event. “The infrastructure that the Human Brain Project has established is already seen as a key building block to facilitate cooperation and research across geographical boundaries, but also across communities.”

Further information about the Human Brain Project as well as photos from research can be found here: https://fz-juelich.sciebo.de/s/hWJkNCC1Hi1PdQ5.

Results highlights and event photos in the online press release.

Results overviews:

– “Human Brain Project: Spotlights on major achievements” and “A closer Look on Scientific

Advances”

– “Human Brain Project: An extensive guide to the tools developed”

Examples of results from the Human Brain Project:

There was a Canadian connection at one time; Montréal Neuro at Canada’s McGill University was involved in developing a computational platform for neuroscience (CBRAIN) for HBP according to an announcement in my January 29, 2013 posting. However, there’s no mention of the EU project on the CBRAIN website nor is there mention of a Canadian partner on the EBRAINS website, which seemed the most likely successor to the CBRAIN portion of the HBP project originally mentioned in 2013.

In any event, the statement from Astrid Lambrecht offers an interesting contrast to that offered by the leader of the other project.

The flagship’s lead institution, Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, issued an August 28, 2023 press release by Lisa Gahnertz (also on the Graphene Flagship website but published September 4, 2023) touting its achievement with an ebullience I am more accustomed to seeing in US news releases,

Chalmers steers Europe’s major graphene venture to success

For the past decade, the Graphene Flagship, the EU’s largest ever research programme, has been coordinated from Chalmers with Jari Kinaret at the helm. As the project reaches the ten-year mark, expectations have been realised, a strong European research field on graphene has been established, and the journey will continue.

‘Have we delivered what we promised?’ asks Graphene Flagship Director Jari Kinaret from his office in the physics department at Chalmers, overlooking the skyline of central Gothenburg.

‘Yes, we have delivered more than anyone had a right to expect,’ [emphasis mine] he says. ‘In our analysis for the conclusion of the project, we read the documents that were written at the start. What we promised then were over a hundred specific things. Some of them were scientific and technological promises, and they have all been fulfilled. Others were for specific applications, and here 60–70 per cent of what was promised has been delivered. We have also delivered applications we did not promise from the start, but these are more difficult to quantify.’

The autumn of 2013 saw the launch of the massive ten-year Science, Technology and Innovation research programme on graphene and other related two-dimensional materials. Joint funding from the European Commission and EU Member States totalled a staggering €1,000 million. A decade later, it is clear that the large-scale initiative has succeeded in its endeavours. According to a report by the research institute WifOR, the Graphene Flagship will have created a total contribution to GDP of €3,800 million and 38,400 new jobs in the 27 EU countries between 2014 and 2030.

Exceeded expectations

‘Per euro invested and compared to other EU projects, the flagship has performed 13 times better than expected in terms of patent applications, and seven times better for scientific publications. We have 17 spin-off companies that have received over €130 million in private funding – people investing their own money is a real example of trust in the fact that the technology works,’ says Jari Kinaret.

He emphasises that the long time span has been crucial in developing the concepts of the various flagship projects.

‘When it comes to new projects, the ability to work on a long timescale is a must and is more important than a large budget. It takes a long time to build trust, both in one another within a team and in the technology on the part of investors, industry and the wider community. The size of the project has also been significant. There has been an ecosystem around the material, with many graphene manufacturers and other organisations involved. It builds robustness, which means you have the courage to invest in the material and develop it.’

From lab to application

In 2010, Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov of the University of Manchester won the Nobel Prize in Physics for their pioneering experiments isolating the ultra-light and ultra-thin material graphene. It was the first known 2D material and stunned the world with its ‘exceptional properties originating in the strange world of quantum physics’ according to the Nobel Foundation’s press release. Many potential applications were identified for this electrically conductive, heat-resistant and light-transmitting material. Jari Kinaret’s research team had been exploring the material since 2006, and when Kinaret learned of the European Commission’s call for a ten-year research programme, it prompted him to submit an application. The Graphene Flagship was initiated to ensure that Europe would maintain its leading position in graphene research and innovation, and its coordination and administration fell to Chalmers.

Is it a staggering thought that your initiative became the biggest EU research project of all time?

‘The fact that the three-minute presentation I gave at a meeting in Brussels has grown into an activity in 22 countries, with 170 organisations and 1,300 people involved … You can’t think about things like that because it can easily become overwhelming. Sometimes you just have to go for it,’ says Jari Kinaret.

One of the objectives of the Graphene Flagship was to take the hopes for this material and move them from lab to application. What has happened so far?

‘We are well on track with 100 products priced and on their way to the market. Many of them are business-to-business products that are not something we ordinary consumers are going to buy, but which may affect us indirectly.’

‘It’s important to remember that getting products to the application stage is a complex process. For a researcher, it may take ten working prototypes; for industry, ten million. Everything has to click into place, on a large scale. All components must work identically and in exactly the same way, and be compatible with existing production in manufacturing as you cannot rebuild an entire factory for a new material. In short, it requires reliability, reproducibility and manufacturability.’

Applications in a wide range of areas

Graphene’s extraordinary properties are being used to deliver the next generation of technologies in a wide range of fields, such as sensors for self-driving cars, advanced batteries, new water purification methods and sophisticated instruments for use in neuroscience. When asked if there are any applications that Jani Kinaret himself would like to highlight, he mentions, among other things, the applications that are underway in the automotive industry – such as sensors to detect obstacles for self-driving cars. Thanks to graphene, they will be so cost-effective to produce that it will be possible to make them available in more than just the most expensive car models.

He also highlights the aerospace industry, where a graphene material for removing ice from aircraft and helicopter wings is under development for the Airbus company. Another favourite, which he has followed from basic research to application, is the development of an air cleaner for Lufthansa passenger aircraft, based on a kind of ‘graphene foam’. Because graphene foam is very light, it can be heated extremely quickly. A pulse of electricity lasting one thousandth of a second is enough to raise the temperature to 300 degrees, thus killing micro-organisms and effectively cleaning the air in the aircraft.

He also mentions the Swedish company ABB, which has developed a graphene composite for circuit breakers in switchgear. These circuit breakers are used to protect the electricity network and must be safe to use. The graphene composite replaces the manual lubrication of the circuit breakers, resulting in significant cost savings.

‘We also see graphene being used in medical technology, but its application requires many years of testing and approval by various bodies. For example, graphene technology can more effectively map the brain before neurosurgery, as it provides a more detailed image. Another aspect of graphene is that it is soft and pliable. This means it can be used for electrodes that are implanted in the brain to treat tremors in Parkinson’s patients, without the electrodes causing scarring,’ says Jari Kinaret.

Coordinated by Chalmers

Jari Kinaret sees the fact that the EU chose Chalmers as the coordinating university as a favourable factor for the Graphene Flagship.

‘Hundreds of millions of SEK [Swedish Kroner] have gone into Chalmers research, but what has perhaps been more important is that we have become well-known and visible in certain areas. We also have the 2D-Tech competence centre and the SIO Grafen programme, both funded by Vinnova and coordinated by Chalmers and Chalmers industriteknik respectively. I think it is excellent that Chalmers was selected, as there could have been too much focus on the coordinating organisation if it had been more firmly established in graphene research at the outset.’

What challenges have been encountered during the project?

‘With so many stakeholders involved, we are not always in agreement. But that is a good thing. A management book I once read said that if two parties always agree, then one is redundant. At the start of the project, it was also interesting to see the major cultural differences we had in our communications and that different cultures read different things between the lines; it took time to realise that we should be brutally straightforward in our communications with one another.’

What has it been like to have the coordinating role that you have had?

‘Obviously, I’ve had to worry about things an ordinary physics professor doesn’t have to worry about, like a phone call at four in the morning after the Brexit vote or helping various parties with intellectual property rights. I have read more legal contracts than I thought I would ever have to read as a professor. As a researcher, your approach when you go into a role is narrow and deep, here it was rather all about breadth. I would have liked to have both, but there are only 26 hours in a day,’ jokes Jari Kinaret.

New phase for the project and EU jobs to come

A new assignment now awaits Jari Kinaret outside Chalmers as Chief Executive Officer of the EU initiative KDT JU (Key Digital Technologies Joint Undertaking, soon to become Chips JU), where industry and the public sector interact to drive the development of new electronic components and systems.

The Graphene Flagship may have reached its destination in its current form, but the work started is progressing in a form more akin to a flotilla. About a dozen projects will continue to live on under the auspices of the European Commission’s Horizon Europe programme. Chalmers is going to coordinate a smaller CSA project called GrapheneEU, where CSA stands for ‘Coordination and Support Action’. It will act as a cohesive force between the research and innovation projects that make up the next phase of the flagship, offering them a range of support and services, including communication, innovation and standardisation.

The Graphene Flagship is about to turn ten. If the project had been a ten-year-old child, what kind of child would it have been?

‘It would have been a very diverse organism. Different aspirations are beginning to emerge – perhaps it is adolescence that is approaching. In addition, within the project we have also studied other related 2D materials, and we found that there are 6,000 distinct materials of this type, of which only about 100 have been studied. So, it’s the younger siblings that are starting to arrive now.’

Facts about the Graphene Flagship:

The Graphene Flagship is the first European flagship for future and emerging technologies. It has been coordinated and administered from the Department of Physics at Chalmers, and as the project enters its next phase, GrapheneEU, coordination will continue to be carried out by staff currently working on the flagship led by Chalmers Professor Patrik Johansson.

The project has proved highly successful in developing graphene-based technology in Europe, resulting in 17 new companies, around 100 new products, nearly 500 patent applications and thousands of scientific papers. All in all, the project has exceeded the EU’s targets for utilisation from research projects by a factor of ten. According to the assessment of the EU research programme Horizon 2020, Chalmers’ coordination of the flagship has been identified as one of the key factors behind its success.

Graphene Week will be held at the Svenska Mässan in Gothenburg from 4 to 8 September 2023. Graphene Week is an international conference, which also marks the finale of the ten-year anniversary of the Graphene Flagship. The conference will be jointly led by academia and industry – Professor Patrik Johansson from Chalmers and Dr Anna Andersson from ABB – and is expected to attract over 400 researchers from Sweden, Europe and the rest of the world. The programme includes an exhibition, press conference and media activities, special sessions on innovation, diversity and ethics, and several technical sessions. The full programme is available here.

Read the press release on Graphene Week from 4 to 8 September and the overall results of the Graphene Flagship. …

Ten years and €1B each. Congratulations to the organizers on such massive undertakings. As for whether or not (and how they’ve been successful), I imagine time will tell.