There’s not much happening in the 2017-18 budget in terms of new spending according to Paul Wells’ March 22, 2017 article for TheStar.com,

This is the 22nd or 23rd federal budget I’ve covered. And I’ve never seen the like of the one Bill Morneau introduced on Wednesday [March 22, 2017].

Not even in the last days of the Harper Conservatives did a budget provide for so little new spending — $1.3 billion in the current budget year, total, in all fields of government. That’s a little less than half of one per cent of all federal program spending for this year.

But times are tight. The future is a place where we can dream. So the dollars flow more freely in later years. In 2021-22, the budget’s fifth planning year, new spending peaks at $8.2 billion. Which will be about 2.4 per cent of all program spending.

…

He’s not alone in this 2017 federal budget analysis; CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) pundits, Chantal Hébert, Andrew Coyne, and Jennifer Ditchburn said much the same during their ‘At Issue’ segment of the March 22, 2017 broadcast of The National (news).

Before I focus on the science and technology budget, here are some general highlights from the CBC’s March 22, 2017 article on the 2017-18 budget announcement (Note: Links have been removed,

Here are highlights from the 2017 federal budget:

- Deficit: $28.5 billion, up from $25.4 billion projected in the fall.

- Trend: Deficits gradually decline over next five years — but still at $18.8 billion in 2021-22.

- Housing: $11.2 billion over 11 years, already budgeted, will go to a national housing strategy.

- Child care: $7 billion over 10 years, already budgeted, for new spaces, starting 2018-19.

- Indigenous: $3.4 billion in new money over five years for infrastructure, health and education.

- Defence: $8.4 billion in capital spending for equipment pushed forward to 2035.

- Care givers: New care-giving benefit up to 15 weeks, starting next year.

- Skills: New agency to research and measure skills development, starting 2018-19.

- Innovation: $950 million over five years to support business-led “superclusters.”

- Startups: $400 million over three years for a new venture capital catalyst initiative.

- AI: $125 million to launch a pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy.

- Coding kids: $50 million over two years for initiatives to teach children to code.

- Families: Option to extend parental leave up to 18 months.

- Uber tax: GST to be collected on ride-sharing services.

- Sin taxes: One cent more on a bottle of wine, five cents on 24 case of beer.

- Bye-bye: No more Canada Savings Bonds.

- Transit credit killed: 15 per cent non-refundable public transit tax credit phased out this year.

You can find the entire 2017-18 budget here.

Science and the 2017-18 budget

For anyone interested in the science news, you’ll find most of that in the 2017 budget’s Chapter 1 — Skills, Innovation and Middle Class jobs. As well, Wayne Kondro has written up a précis in his March 22, 2017 article for Science (magazine),

Finance officials, who speak on condition of anonymity during the budget lock-up, indicated the budgets of the granting councils, the main source of operational grants for university researchers, will be “static” until the government can assess recommendations that emerge from an expert panel formed in 2015 and headed by former University of Toronto President David Naylor to review basic science in Canada [highlighted in my June 15, 2016 posting ; $2M has been allocated for the advisor and associated secretariat]. Until then, the officials said, funding for the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) will remain at roughly $848 million, whereas that for the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) will remain at $773 million, and for the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council [SSHRC] at $547 million.

NSERC, though, will receive $8.1 million over 5 years to administer a PromoScience Program that introduces youth, particularly unrepresented groups like Aboriginal people and women, to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics through measures like “space camps and conservation projects.” CIHR, meanwhile, could receive modest amounts from separate plans to identify climate change health risks and to reduce drug and substance abuse, the officials added.

… Canada’s Innovation and Skills Plan, would funnel $600 million over 5 years allocated in 2016, and $112.5 million slated for public transit and green infrastructure, to create Silicon Valley–like “super clusters,” which the budget defined as “dense areas of business activity that contain large and small companies, post-secondary institutions and specialized talent and infrastructure.” …

…

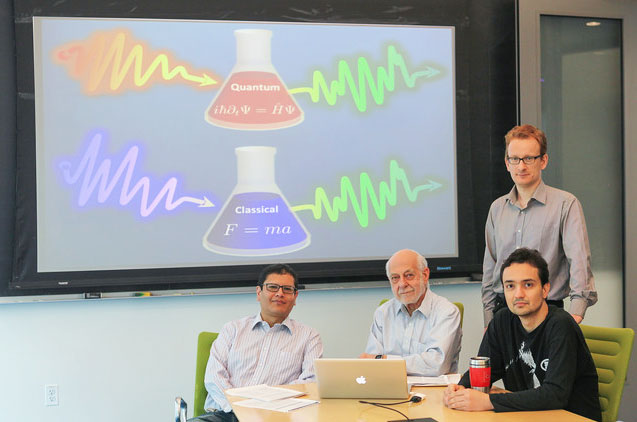

… The Canadian Institute for Advanced Research will receive $93.7 million [emphasis mine] to “launch a Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy … (to) position Canada as a world-leading destination for companies seeking to invest in artificial intelligence and innovation.”

…

… Among more specific measures are vows to: Use $87.7 million in previous allocations to the Canada Research Chairs program to create 25 “Canada 150 Research Chairs” honoring the nation’s 150th year of existence, provide $1.5 million per year to support the operations of the office of the as-yet-unappointed national science adviser [see my Dec. 7, 2016 post for information about the job posting, which is now closed]; provide $165.7 million [emphasis mine] over 5 years for the nonprofit organization Mitacs to create roughly 6300 more co-op positions for university students and grads, and provide $60.7 million over five years for new Canadian Space Agency projects, particularly for Canadian participation in the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s next Mars Orbiter Mission.

Kondros was either reading an earlier version of the budget or made an error regarding Mitacs (from the budget in the “A New, Ambitious Approach to Work-Integrated Learning” subsection),

Mitacs has set an ambitious goal of providing 10,000 work-integrated learning placements for Canadian post-secondary students and graduates each year—up from the current level of around 3,750 placements. Budget 2017 proposes to provide $221 million [emphasis mine] over five years, starting in 2017–18, to achieve this goal and provide relevant work experience to Canadian students.

As well, the budget item for the Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy is $125M.

Moving from Kondros’ précis, the budget (in the “Positioning National Research Council Canada Within the Innovation and Skills Plan” subsection) announces support for these specific areas of science,

Stem Cell Research

The Stem Cell Network, established in 2001, is a national not-for-profit organization that helps translate stem cell research into clinical applications, commercial products and public policy. Its research holds great promise, offering the potential for new therapies and medical treatments for respiratory and heart diseases, cancer, diabetes, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, Crohn’s disease, auto-immune disorders and Parkinson’s disease. To support this important work, Budget 2017 proposes to provide the Stem Cell Network with renewed funding of $6 million in 2018–19.

Space Exploration

Canada has a long and proud history as a space-faring nation. As our international partners prepare to chart new missions, Budget 2017 proposes investments that will underscore Canada’s commitment to innovation and leadership in space. Budget 2017 proposes to provide $80.9 million on a cash basis over five years, starting in 2017–18, for new projects through the Canadian Space Agency that will demonstrate and utilize Canadian innovations in space, including in the field of quantum technology as well as for Mars surface observation. The latter project will enable Canada to join the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA’s) next Mars Orbiter Mission.

Quantum Information

The development of new quantum technologies has the potential to transform markets, create new industries and produce leading-edge jobs. The Institute for Quantum Computing is a world-leading Canadian research facility that furthers our understanding of these innovative technologies. Budget 2017 proposes to provide the Institute with renewed funding of $10 million over two years, starting in 2017–18.

Social Innovation

Through community-college partnerships, the Community and College Social Innovation Fund fosters positive social outcomes, such as the integration of vulnerable populations into Canadian communities. Following the success of this pilot program, Budget 2017 proposes to invest $10 million over two years, starting in 2017–18, to continue this work.

International Research Collaborations

The Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) connects Canadian researchers with collaborative research networks led by eminent Canadian and international researchers on topics that touch all humanity. Past collaborations facilitated by CIFAR are credited with fostering Canada’s leadership in artificial intelligence and deep learning. Budget 2017 proposes to provide renewed and enhanced funding of $35 million over five years, starting in 2017–18.

Earlier this week, I highlighted Canada’s strength in the field of regenerative medicine, specifically stem cells in a March 21, 2017 posting. The $6M in the current budget doesn’t look like increased funding but rather a one-year extension. I’m sure they’re happy to receive it but I imagine it’s a little hard to plan major research projects when you’re not sure how long your funding will last.

As for Canadian leadership in artificial intelligence, that was news to me. Here’s more from the budget,

Canada a Pioneer in Deep Learning in Machines and Brains

CIFAR’s Learning in Machines & Brains program has shaken up the field of artificial intelligence by pioneering a technique called “deep learning,” a computer technique inspired by the human brain and neural networks, which is now routinely used by the likes of Google and Facebook. The program brings together computer scientists, biologists, neuroscientists, psychologists and others, and the result is rich collaborations that have propelled artificial intelligence research forward. The program is co-directed by one of Canada’s foremost experts in artificial intelligence, the Université de Montréal’s Yoshua Bengio, and for his many contributions to the program, the University of Toronto’s Geoffrey Hinton, another Canadian leader in this field, was awarded the title of Distinguished Fellow by CIFAR in 2014.

Meanwhile, from chapter 1 of the budget in the subsection titled “Preparing for the Digital Economy,” there is this provision for children,

Providing educational opportunities for digital skills development to Canadian girls and boys—from kindergarten to grade 12—will give them the head start they need to find and keep good, well-paying, in-demand jobs. To help provide coding and digital skills education to more young Canadians, the Government intends to launch a competitive process through which digital skills training organizations can apply for funding. Budget 2017 proposes to provide $50 million over two years, starting in 2017–18, to support these teaching initiatives.

I wonder if BC Premier Christy Clark is heaving a sigh of relief. At the 2016 #BCTECH Summit, she announced that students in BC would learn to code at school and in newly enhanced coding camp programmes (see my Jan. 19, 2016 posting). Interestingly, there was no mention of additional funding to support her initiative. I guess this money from the federal government comes at a good time as we will have a provincial election later this spring where she can announce the initiative again and, this time, mention there’s money for it.

Attracting brains from afar

Ivan Semeniuk in his March 23, 2017 article (for the Globe and Mail) reads between the lines to analyze the budget’s possible impact on Canadian science,

But a between-the-lines reading of the budget document suggests the government also has another audience in mind: uneasy scientists from the United States and Britain.

The federal government showed its hand at the 2017 #BCTECH Summit. From a March 16, 2017 article by Meera Bains for the CBC news online,

At the B.C. tech summit, Navdeep Bains, Canada’s minister of innovation, said the government will act quickly to fast track work permits to attract highly skilled talent from other countries.

“We’re taking the processing time, which takes months, and reducing it to two weeks for immigration processing for individuals [who] need to come here to help companies grow and scale up,” Bains said.

“So this is a big deal. It’s a game changer.”

That change will happen through the Global Talent Stream, a new program under the federal government’s temporary foreign worker program. It’s scheduled to begin on June 12, 2017.

U.S. companies are taking notice and a Canadian firm, True North, is offering to help them set up shop.

“What we suggest is that they think about moving their operations, or at least a chunk of their operations, to Vancouver, set up a Canadian subsidiary,” said the company’s founder, Michael Tippett.

“And that subsidiary would be able to house and accommodate those employees.”

Industry experts says while the future is unclear for the tech sector in the U.S., it’s clear high tech in B.C. is gearing up to take advantage.

US business attempts to take advantage of Canada’s relative stability and openness to immigration would seem to be the motive for at least one cross border initiative, the Cascadia Urban Analytics Cooperative. From my Feb. 28, 2017 posting,

There was some big news about the smallest version of the Cascadia region on Thursday, Feb. 23, 2017 when the University of British Columbia (UBC) , the University of Washington (state; UW), and Microsoft announced the launch of the Cascadia Urban Analytics Cooperative. From the joint Feb. 23, 2017 news release (read on the UBC website or read on the UW website),

In an expansion of regional cooperation, the University of British Columbia and the University of Washington today announced the establishment of the Cascadia Urban Analytics Cooperative to use data to help cities and communities address challenges from traffic to homelessness. The largest industry-funded research partnership between UBC and the UW, the collaborative will bring faculty, students and community stakeholders together to solve problems, and is made possible thanks to a $1-million gift from Microsoft.

…

Today’s announcement follows last September’s [2016] Emerging Cascadia Innovation Corridor Conference in Vancouver, B.C. The forum brought together regional leaders for the first time to identify concrete opportunities for partnerships in education, transportation, university research, human capital and other areas.

A Boston Consulting Group study unveiled at the conference showed the region between Seattle and Vancouver has “high potential to cultivate an innovation corridor” that competes on an international scale, but only if regional leaders work together. The study says that could be possible through sustained collaboration aided by an educated and skilled workforce, a vibrant network of research universities and a dynamic policy environment.

It gets better, it seems Microsoft has been positioning itself for a while if Matt Day’s analysis is correct (from my Feb. 28, 2017 posting),

Matt Day in a Feb. 23, 2017 article for the The Seattle Times provides additional perspective (Note: Links have been removed),

Microsoft’s effort to nudge Seattle and Vancouver, B.C., a bit closer together got an endorsement Thursday [Feb. 23, 2017] from the leading university in each city.

…

The partnership has its roots in a September [2016] conference in Vancouver organized by Microsoft’s public affairs and lobbying unit [emphasis mine.] That gathering was aimed at tying business, government and educational institutions in Microsoft’s home region in the Seattle area closer to its Canadian neighbor.

Microsoft last year [2016] opened an expanded office in downtown Vancouver with space for 750 employees, an outpost partly designed to draw to the Northwest more engineers than the company can get through the U.S. guest worker system [emphasis mine].

This was all prior to President Trump’s legislative moves in the US, which have at least one Canadian observer a little more gleeful than I’m comfortable with. From a March 21, 2017 article by Susan Lum for CBC News online,

U.S. President Donald Trump’s efforts to limit travel into his country while simultaneously cutting money from science-based programs provides an opportunity for Canada’s science sector, says a leading Canadian researcher.

“This is Canada’s moment. I think it’s a time we should be bold,” said Alan Bernstein, president of CIFAR [which on March 22, 2017 was awarded $125M to launch the Pan Canada Artificial Intelligence Strategy in the Canadian federal budget announcement], a global research network that funds hundreds of scientists in 16 countries.

Bernstein believes there are many reasons why Canada has become increasingly attractive to scientists around the world, including the political climate in the United States and the Trump administration’s travel bans.

Thankfully, Bernstein calms down a bit,

“It used to be if you were a bright young person anywhere in the world, you would want to go to Harvard or Berkeley or Stanford, or what have you. Now I think you should give pause to that,” he said. “We have pretty good universities here [emphasis mine]. We speak English. We’re a welcoming society for immigrants.”

…

Bernstein cautions that Canada should not be seen to be poaching scientists from the United States — but there is an opportunity.

“It’s as if we’ve been in a choir of an opera in the back of the stage and all of a sudden the stars all left the stage. And the audience is expecting us to sing an aria. So we should sing,” Bernstein said.

Bernstein said the federal government, with this week’s so-called innovation budget, can help Canada hit the right notes.

“Innovation is built on fundamental science, so I’m looking to see if the government is willing to support, in a big way, fundamental science in the country.”

Pretty good universities, eh? Thank you, Dr. Bernstein, for keeping some of the boosterism in check. Let’s leave the chest thumping to President Trump and his cronies.

Ivan Semeniuk’s March 23, 2017 article (for the Globe and Mail) provides more details about the situation in the US and in Britain,

Last week, Donald Trump’s first budget request made clear the U.S. President would significantly reduce or entirely eliminate research funding in areas such as climate science and renewable energy if permitted by Congress. Even the National Institutes of Health, which spearheads medical research in the United States and is historically supported across party lines, was unexpectedly targeted for a $6-billion (U.S.) cut that the White House said could be achieved through “efficiencies.”

In Britain, a recent survey found that 42 per cent of academics were considering leaving the country over worries about a less welcoming environment and the loss of research money that a split with the European Union is expected to bring.

In contrast, Canada’s upbeat language about science in the budget makes a not-so-subtle pitch for diversity and talent from abroad, including $117.6-million to establish 25 research chairs with the aim of attracting “top-tier international scholars.”

For good measure, the budget also includes funding for science promotion and $2-million annually for Canada’s yet-to-be-hired Chief Science Advisor, whose duties will include ensuring that government researchers can speak freely about their work.

“What we’ve been hearing over the last few months is that Canada is seen as a beacon, for its openness and for its commitment to science,” said Ms. Duncan [Kirsty Duncan, Minister of Science], who did not refer directly to either the United States or Britain in her comments.

Providing a less optimistic note, Erica Alini in her March 22, 2017 online article for Global News mentions a perennial problem, the Canadian brain drain,

The budget includes a slew of proposed reforms and boosted funding for existing training programs, as well as new skills-development resources for unemployed and underemployed Canadians not covered under current EI-funded programs.

There are initiatives to help women and indigenous people get degrees or training in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (the so-called STEM subjects) and even to teach kids as young as kindergarten-age to code.

But there was no mention of how to make sure Canadians with the right skills remain in Canada, TD’s DePratto {Toronto Dominion Bank} Economics; TD is currently experiencing a scandal {March 13, 2017 Huffington Post news item}] told Global News.

Canada ranks in the middle of the pack compared to other advanced economies when it comes to its share of its graduates in STEM fields, but the U.S. doesn’t shine either, said DePratto [Brian DePratto, senior economist at TD .

The key difference between Canada and the U.S. is the ability to retain domestic talent and attract brains from all over the world, he noted.

To be blunt, there may be some opportunities for Canadian science but it does well to remember (a) US businesses have no particular loyalty to Canada and (b) all it takes is an election to change any perceived advantages to disadvantages.

Digital policy and intellectual property issues

Dubbed by some as the ‘innovation’ budget (official title: Building a Strong Middle Class), there is an attempt to address a longstanding innovation issue (from a March 22, 2017 posting by Michael Geist on his eponymous blog (Note: Links have been removed),

The release of today’s [march 22, 2017] federal budget is expected to include a significant emphasis on innovation, with the government revealing how it plans to spend (or re-allocate) hundreds of millions of dollars that is intended to support innovation. Canada’s dismal innovation record needs attention, but spending our way to a more innovative economy is unlikely to yield the desired results. While Navdeep Bains, the Innovation, Science and Economic Development Minister, has talked for months about the importance of innovation, Toronto Star columnist Paul Wells today delivers a cutting but accurate assessment of those efforts:

“This government is the first with a minister for innovation! He’s Navdeep Bains. He frequently posts photos of his meetings on Twitter, with the hashtag “#innovation.” That’s how you know there is innovation going on. A year and a half after he became the minister for #innovation, it’s not clear what Bains’s plans are. It’s pretty clear that within the government he has less than complete control over #innovation. There’s an advisory council on economic growth, chaired by the McKinsey guru Dominic Barton, which periodically reports to the government urging more #innovation.

There’s a science advisory panel, chaired by former University of Toronto president David Naylor, that delivered a report to Science Minister Kirsty Duncan more than three months ago. That report has vanished. One presumes that’s because it offered some advice. Whatever Bains proposes, it will have company.”

Wells is right. Bains has been very visible with plenty of meetings and public photo shoots but no obvious innovation policy direction. This represents a missed opportunity since Bains has plenty of policy tools at his disposal that could advance Canada’s innovation framework without focusing on government spending.

For example, Canada’s communications system – wireless and broadband Internet access – falls directly within his portfolio and is crucial for both business and consumers. Yet Bains has been largely missing in action on the file. He gave approval for the Bell – MTS merger that virtually everyone concedes will increase prices in the province and make the communications market less competitive. There are potential policy measures that could bring new competitors into the market (MVNOs [mobile virtual network operators] and municipal broadband) and that could make it easier for consumers to switch providers (ban on unlocking devices). Some of this falls to the CRTC, but government direction and emphasis would make a difference.

Even more troubling has been his near total invisibility on issues relating to new fees or taxes on Internet access and digital services. Canadian Heritage Minister Mélanie Joly has taken control of the issue with the possibility that Canadians could face increased costs for their Internet access or digital services through mandatory fees to contribute to Canadian content. Leaving aside the policy objections to such an approach (reducing affordable access and the fact that foreign sources now contribute more toward Canadian English language TV production than Canadian broadcasters and distributors), Internet access and e-commerce are supposed to be Bains’ issue and they have a direct connection to the innovation file. How is it possible for the Innovation, Science and Economic Development Minister to have remained silent for months on the issue?

Bains has been largely missing on trade related innovation issues as well. My Globe and Mail column today focuses on a digital-era NAFTA, pointing to likely U.S. demands on data localization, data transfers, e-commerce rules, and net neutrality. These are all issues that fall under Bains’ portfolio and will impact investment in Canadian networks and digital services. There are innovation opportunities for Canada here, but Bains has been content to leave the policy issues to others, who will be willing to sacrifice potential gains in those areas.

Intellectual property policy is yet another area that falls directly under Bains’ mandate with an obvious link to innovation, but he has done little on the file. Canada won a huge NAFTA victory late last week involving the Canadian patent system, which was challenged by pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly. Why has Bains not promoted the decision as an affirmation of how Canada’s intellectual property rules?

On the copyright front, the government is scheduled to conduct a review of the Copyright Act later this year, but it is not clear whether Bains will take the lead or again cede responsibility to Joly. The Copyright Act is statutorily under the Industry Minister and reform offers the chance to kickstart innovation. …

For anyone who’s not familiar with this area, innovation is often code for commercialization of science and technology research efforts. These days, digital service and access policies and intellectual property policies are all key to research and innovation efforts.

The country that’s most often (except in mainstream Canadian news media) held up as an example of leadership in innovation is Estonia. The Economist profiled the country in a July 31, 2013 article and a July 7, 2016 article on apolitical.co provides and update.

Conclusions

Science monies for the tri-council science funding agencies (NSERC, SSHRC, and CIHR) are more or less flat but there were a number of line items in the federal budget which qualify as science funding. The $221M over five years for Mitacs, the $125M for the Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy, additional funding for the Canada research chairs, and some of the digital funding could also be included as part of the overall haul. This is in line with the former government’s (Stephen Harper’s Conservatives) penchant for keeping the tri-council’s budgets under control while spreading largesse elsewhere (notably the Perimeter Institute, TRIUMF [Canada’s National Laboratory for Particle and Nuclear Physics], and, in the 2015 budget, $243.5-million towards the Thirty Metre Telescope (TMT) — a massive astronomical observatory to be constructed on the summit of Mauna Kea, Hawaii, a $1.5-billion project). This has lead to some hard feelings in the past with regard to ‘big science’ projects getting what some have felt is an undeserved boost in finances while the ‘small fish’ are left scrabbling for the ever-diminishing (due to budget cuts in years past and inflation) pittances available from the tri-council agencies.

Mitacs, which started life as a federally funded Network Centre for Excellence focused on mathematics, has since shifted focus to become an innovation ‘champion’. You can find Mitacs here and you can find the organization’s March 2016 budget submission to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance here. At the time, they did not request a specific amount of money; they just asked for more.

The amount Mitacs expects to receive this year is over $40M which represents more than double what they received from the federal government and almost of 1/2 of their total income in the 2015-16 fiscal year according to their 2015-16 annual report (see p. 327 for the Mitacs Statement of Operations to March 31, 2016). In fact, the federal government forked over $39,900,189. in the 2015-16 fiscal year to be their largest supporter while Mitacs’ total income (receipts) was $81,993,390.

It’s a strange thing but too much money, etc. can be as bad as too little. I wish the folks Mitacs nothing but good luck with their windfall.

I don’t see anything in the budget that encourages innovation and investment from the industrial sector in Canada.

Finallyl, innovation is a cultural issue as much as it is a financial issue and having worked with a number of developers and start-up companies, the most popular business model is to develop a successful business that will be acquired by a large enterprise thereby allowing the entrepreneurs to retire before the age of 30 (or 40 at the latest). I don’t see anything from the government acknowledging the problem let alone any attempts to tackle it.

All in all, it was a decent budget with nothing in it to seriously offend anyone.