I’ve always wondered where buckyballs come from (as have scientists for the last 25 years) and now there’s an answer of sorts (from the July 31, 2012 Florida State University news release Note: I have removed some links),

“We started with a paste of pre-existing fullerene molecules mixed with carbon and helium, shot it with a laser, and instead of destroying the fullerenes we were surprised to find they’d actually grown,” they wrote. The fullerenes were able to absorb and incorporate carbon from the surrounding gas.

By using fullenes that contained heavy metal atoms in their centers, the scientists showed that the carbon cages remained closed throughout the process.

“If the cages grew by splitting open, we would have lost the metal atoms, but they always stayed locked inside,” Dunk [Paul Dunk, a doctoral student in chemistry and biochemistry at Florida State and lead author of the study published in Nature Communications] noted.

The researchers worked with a team of MagLab chemists using the lab’s 9.4-tesla Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer to analyze the dozens of molecular species produced when they shot the fullerene paste with the laser. The instrument works by separating molecules according to their masses, allowing the researchers to identify the types and numbers of atoms in each molecule. The process is used for applications as diverse as identifying oil spills, biomarkers and protein structures.

Dexter Johnson in his Aug. 6, 2012 posting on the Nanoclast blog on the IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) provides some context and commentary (Note: I have removed a link),

When Richard Smalley, Robert Curl, James Heath, Sean O’Brien, and Harold Kroto prepared the first buckminsterfullerene (C60) (or buckyball), they kicked off the next 25 years of nanomaterial science.

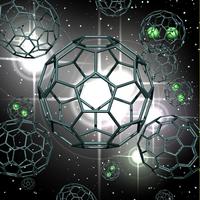

Here’s an artist’s illustration of what these scientists have achieved, fullerene cage growth,

An artist’s representation of fullerene cage growth via carbon absorption from surrounding hot gases. Some of the cages contain lanthanum metal atoms. (Image courtesy National Science Foundation) [downloaded from Florida State University website]

Many people know the buckyball, also known by scientists as buckminsterfullerene, carbon 60 or C60, from the covers of their school chemistry textbooks. Indeed, the molecule represents the iconic image of “chemistry.” But how these often highly symmetrical, beautiful molecules with fascinating properties form in the first place has been a mystery for a quarter-century. Despite worldwide investigation since the 1985 discovery of C60, buckminsterfullerene and other, non-spherical C60 molecules — known collectively as fullerenes — have kept their secrets. How? They’re born under highly energetic conditions and grow ultra-fast, making them difficult to analyze.

“The difficulty with fullerene formation is that the process is literally over in a flash — it’s next to impossible to see how the magic trick of their growth was performed,” said Paul Dunk, a doctoral student in chemistry and biochemistry at Florida State and lead author of the work.

There’s more than just idle curiosity at work (from the news release),

The buckyball research results will be important for understanding fullerene formation in extraterrestrial environments. Recent reports by NASA showed that crystals of C60 are in orbit around distant suns. This suggests that fullerenes may be more common in the universe than previously thought.

“The results of our study will surely be extremely valuable in deciphering fullerene formation in extraterrestrial environments,” said Florida State’s Harry Kroto, a Nobel Prize winner for the discovery of C60 and co-author of the current study.

The results also provide fundamental insight into self-assembly of other technologically important carbon nanomaterials such as nanotubes and the new wunderkind of the carbon family, graphene.

H/T to Nanowerk’s July 31, 2012 news item titled, Decades-old mystery how buckyballs form has been solved. In addition to Florida State University, National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (or MagLab), the CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique)Institute of Materials in France and Nagoya University in Japan were also involved in the research.