Racism and social justice are two themes often found in the works featured at the Rennie Museum (formerly Rennie Collection). Local real estate marketer, Bob Rennie has been showing works there from his collection since at least 2009 when I wrote my first commentary about it (December 4, 2009).

Kerry James Marshall, the latest artist to have his work featured (June 2 – November 3, 2018), carries on the tradition while making those artistic ‘themes’ his own n a breathtaking (in both its positive and negative meanings) range of styles and media.

Here’s a brief description of some of the works, from an undated Rennie Museum press release,

Rennie Museum presents a survey of works by Kerry James Marshall spanning thirty-two years of the artist’s career. Kerry James Marshall: Collected Works features pieces from the artist’s complex body of work, which interrogates the sparse historical presence of African-Americans through painting, sculpture, drawing and other media. …

The sculptural installation Untitled (Black Power Stamps) (1998) [emphasis mine], Marshall’s very first work acquired by Bob Rennie, aptly sets the tone of the exhibition. Five colossal stamps and their corresponding ink pads are dispersed over the floor of the museum’s four-story high gallery space. Inscribed on each stamp, and reiterated on the walls, are phrases of power dating back to the Civil Rights Movement: ‘Black is Beautiful’, ‘Black Power’, ‘We Shall Overcome’, ‘By Any Means Necessary’, and ‘Burn Baby Burn’. The sentiment reverberates through the three 18 feet (5.5 metre) wide paintings installed in the same room, respectively titled Untitled (Red) (2011), Untitled (Black) and Untitled (Green) (2012). Exhibited together for the first time in North America, the imposing paintings with their colours saluting the Pan African flag echo the form of Barnett Newman’s Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III (1967).

Commanding attention in the center of another room is Wake (2003-2005) [emphasis mine], a sculptural work that focuses on the collective trauma of slavery. Draped atop a blackened model sailboat is a web of medallions featuring portraits of descendants of the approximately twenty African slaves who first landed in Jamestown, Virginia in 1607. Atop a polished black base evoking the deep seas, the medallions cascade over and behind the mourning vessel in a gilded procession, cast out in the boat’s wake. The work commemorates an entire lineage of people whose lives have been irrevocably affected by the traumatic history of slavery in the United States, while simultaneously celebrating the resilience and vivacity of the culture that flourished from it.

Garden Party (2004-2013) [emphasis mine] is a long-coveted painting that Marshall re-worked over the course of almost ten years. Created in a style that harkens 19th century impressionist paintings, the work depicts a scene of leisure – an array of multi-ethnic friends and neighbours casually gathered in a backyard of a social housing project. Painted on a flat canvas tarp and hung barely off the floor, the image highlights an often-overlooked perspective of the vibrant everyday life in the projects and invites its viewers to join in the gathering.

In a dimmed room is Invisible Man (1986) [emphasis mine] – a historic work and one of the first to feature Marshall’s now iconic black on black tonal painting. Referencing Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel of the same title, Marshall’s work literalizes the premise of black invisibility. Only distinguishable by his bright-white eyes and teeth, and the subtle warmth that delineates black body from black background, Marshall’s figure, like Ellison’s protagonist, subverts his own invisibility, using colour as an emblem of power rather than of submission. The work’s presentation at Rennie Museum provides an opportunity for viewers to explore the full mastery with which Kerry James Marshall layers his various shades of black.

…

As always, you book a tour or claim a space on a tour (here) to see the latest exhibition and are guided through the gallery spaces. What follows is a series of pictures depicting the Marshall pieces in that first room (from the Rennie Museum’s photographic documentation for Marshall’s work), Note: There are five pages of documentation and I encourage you to look at all five,

Installation View. Courtesy:: Rennie Museum

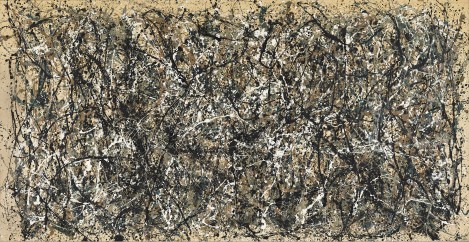

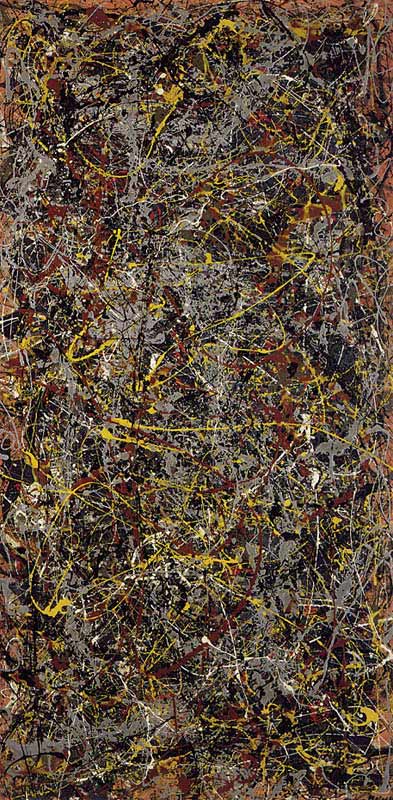

Blot, 2014. acrylic on pvc panel 84 × 119 5/8 × 3 3/8 inches (213 × 304 × 9 cm). Courtesy: Rennie Museum

Sculpture (Ibeji), 2006. wood, fabric, beads 24 × 12 × 14 inches (61 × 30 × 36 cm) Courtesy: Rennie Museum

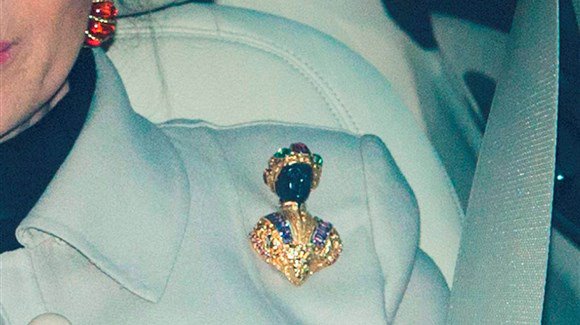

Heirlooms and Accessories, 2002. 3 inkjet prints on wove paper, rhinestone encrusted wooden artist’s frames each: 56 5/8 × 53 3/4 inches (144 × 137 cm) Courtesy: Rennie Museum

I’ve placed the pieces in the order in which I viewed them. Being at the opening event on June 2, 2018 meant that rather than having a tour, we were ‘invited’ to look at the pieces and ask questions of various ‘attendants’ standing nearby. The ‘Blot’, with all that colour, immediate drew my attention and not having read the title of the piece, I commented on its resemblance to a Rorschach Inkblot. It was my only successful guess of the visit and I continue to bask in it.

According to the attendant, in addition to resembling said inkblot, this piece also addresses abstract expressionism and the absence of African American visual artists from the movement. In this piece as with many others, Marshall finds a way to depict absence despite the paradox (a picture of absence) in terms.

‘Heirlooms and Accessories’ is an example of Marshall’s talent for depicting absence. At first glance the piece seems benign. There is a kind of double frame. The outermost frame is white and inside (abutting the artwork) a diamante braid has been added all around it to create a double frame. The braid is very pretty and accentuates the lockets depicted in the image. There are three white women pictured in their lockets and beneath those lockets and the white paint lay images of African Americans being lynched. The women, by the way, were complicit in the lynchings. It was deeply unsettling to learn this as my friend and I had just moments before been admiring the diamante braid.

Marshall’s work seems designed to force the viewer to look beneath the surface, which means stripping away layers, which with ‘Heirlooms’ means that you strip away the whitewashing.

As a white woman, the show is a profoundly disturbing experience. Marshall’s range of materials and mastery are breathtaking (in the positive sense) and the way he seduces the (white) viewer into coming closer and experiencing the painting, metaphorically speaking, as a mirror rather than a picture. Marshall has flipped the viewer’s experience making it impossible (or very difficult) to blame racism on other people while failing to recognize your own sins.

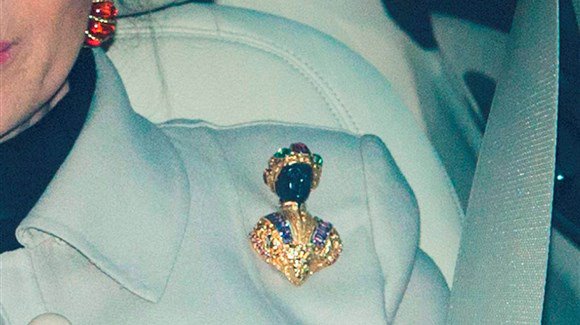

The third piece in the room, the sculpture is a representation of a standard of beauty still not often seen in popular culture in North America. Weirdly, it reminded me of something from a December 21, 2017 posting on the LaineyGossip blog,

[downloaded from http://www.laineygossip.com/princess-michael-of-kent-racist-jewelry-greets-meghan/48728]

I don’t know well you can see this, but it’s an example of ‘Blackamoor jewellery’. The woman wearing it is Princess Michael of Kent and at the time the picture was taken she was on her to a Christmas 2017 lunch with the Queen of England. The lunch is where she was to meet Meghan Markle who describes herself as a woman of mixed race and is now the Duchess of Sussex and married to the Queen’s grandson, Harry. For anyone unfamiliar with ‘Blackmoor art’ here’s a

July 31, 2015 essay by Anneke Rautenbach for New York University,

… Blackamoors—a trope in Italian decorative art especially common in pieces of furniture, but also appearing in paintings, jewelry, and textiles. The motif emerged as an artistic response to the European encounter with the Moors—dark-skinned Muslims from North Africa and the Middle East who came to occupy various parts of Europe during the Middle Ages. Commonly fixed in positions of servitude—as footmen or waiters, for example—the figures personify fantasies of racial conquest.

I trust Princess Michael was made to remove her brooch before entering the palace.

The contrast between Marshall’s sculpture emphasizing the dignity and beauty of the figure and the ‘jewellery’ is striking. The past, as Marshall reminds us, is always with us. From Rautenback’s July 31, 2015 essay (Note: A link has been removed),

Gaudy by nature, and uncomfortably dated—a bit like the American lawn jockey, or Aunt Jemima doll— … Blackamoors are still a thriving industry, with the United States as their no. 1 importer. (In fact, the figurines are especially popular in Texas and Connecticut—search “Blackamoor” online and you’ll find countless listings on eBay, Etsy, and elsewhere.) Unlike their American counterparts, which focus mostly on romanticizing scenes from the era of slavery, these European ornaments often depict black bodies as exotic noblemen. And not everyone considers them passé: As recently as September 2012, the Italian fashion house Dolce & Gabbana invited outrage when it included a caricatured black woman figurine on an earring as part of its spring/summer collection.

Encountering bias and (conscious or unconscious) racism in one’s self is both deeply chastening and a priceless gift. It’s one that comedienne Roseanne Barr seems determined to refuse (from a June 14, 2018 article by Marissa Martinelli for Slate.com (Note: Link have been removed),

Barr […] suggested on Thursday [June 14, 2018] that it is only “low IQ” people who would interpret describing a black woman as “Muslim Brotherhood & planet of the apes had a baby” as racist. The real explanation is apparently much deeper:

Verified account @therealroseanne

…

Low IQ people and Rod Serling’s screenwriting join Ambien and Memorial Day on the growing list of entities that Barr has used to justify the racist tweet over the past two weeks. The one person whose name you will not find on that list of people responsible for what Roseanne Barr said is Roseanne Barr herself.

…

Even with such an obvious tweet, Barr can’t (consistently) admit to and (consistently) apologize for her comment. It may not seem like a gift to her but it is. Facing up to one’s sins and making reparation can help heal the extraordinary wounds that Marshall is making visible.

You may have noticed that I called this show ‘a song of racism’. It’s a reference to poetry which in ancient times was sometimes referred to as a song (Song of Solomon, anyone?). It was also a narrative instrument, i. e., used for storytelling for an active, participatory audience.

Marshall tells a story in allusive language (like poetry) and tricks/seduces you into participating.

On that note, I have one last story to tell and it’s about the placement of Marshall’s artworks in the first floor room. It’s my story, yours and Marshall’s might be different but he has inspired me and so …

The ‘Blot’ or Rorschach Inkblot is a test, which tells a psychologist something about you and how you apprehend the world. It’s the first piece you see when you enter the Rennie Museum space and it sets the tone for all that is to come. What you see says much about you.

The women, in the sculpture and the lockets, provide contrast and, depending on your race, hold a mirror to you. What is ‘other’ and what is ‘you’?

There was religious imagery in much of Marshall’s work elsewhere and I was particularly struck with the hearts that appeared in some of his paintings. I was reminded of the ‘sacred heart’, a key piece of religious iconography usually associated with Roman Catholicism although other religions also use the imagery.

It is a symbol of love and compassion although I’ve always associated it more with guilt. (My mother favoured the version featuring the heart pierced with a crown of thorns.)

Getting back to “What is ‘other’ and what is ‘you’?” Marshall seems to be hinting that after guilt and suffering, forgiveness is possible.

That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

As for Marshall, he is a thoughtful artist asking some difficult questions. I hope you’ll get a chance to see his work at the Rennie Museum. As I write this, every tour through June is completely booked and first set of July tours is getting booked fast. You’d best keep an eagle eye on the Visit page.

ETA June18, 2018: Kerry James Marshall was in Vancouver and gave this talk about his work just prior to the show’s opening: https://vimeo.com/274179397 (It runs for roughly 1 hr. and 49 minutes.)