A Nov. 14, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily describes research that could lead to applications useful for ‘lab-on-a-chip’ operations,

A team of mechanical engineers at the University of California San Diego [UCSD] has successfully used acoustic waves to move fluids through small channels at the nanoscale. The breakthrough is a first step toward the manufacturing of small, portable devices that could be used for drug discovery and microrobotics applications. The devices could be integrated in a lab on a chip to sort cells, move liquids, manipulate particles and sense other biological components. For example, it could be used to filter a wide range of particles, such as bacteria, to conduct rapid diagnosis.

A Nov. 14, 2016 UCSD news release (also on EurrekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more information,

The researchers detail their findings in the Nov. 14 issue of Advanced Functional Materials. This is the first time that surface acoustic waves have been used at the nanoscale.

The field of nanofluidics has long struggled with moving fluids within channels that are 1000 times smaller than the width of a hair, said James Friend, a professor and materials science expert at the Jacobs School of Engineering at UC San Diego. Current methods require bulky and expensive equipment as well as high temperatures. Moving fluid out of a channel that’s just a few nanometers high requires pressures of 1 megaPascal, or the equivalent of 10 atmospheres.

Researchers led by Friend had tried to use acoustic waves to move the fluids along at the nano scale for several years. They also wanted to do this with a device that could be manufactured at room temperature.

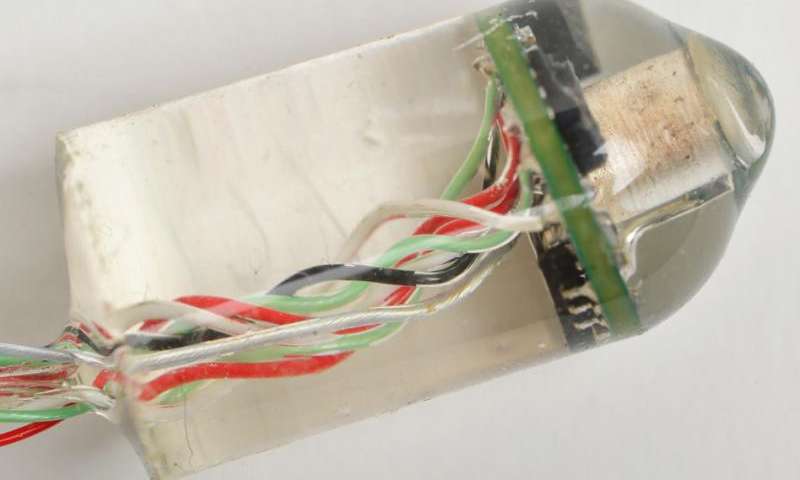

After a year of experimenting, post-doctoral researcher Morteza Miansari, now at Stanford, was able to build a device made of lithium niobate with nanoscale channels where fluids can be moved by surface acoustic waves. This was made possible by a new method Miansari developed to bond the material to itself at room temperature. The fabrication method can be easily scaled up, which would lower manufacturing costs. Building one device would cost $1000 but building 100,000 would drive the price down to $1 each.

The device is compatible with biological materials, cells and molecules.

Researchers used acoustic waves with a frequency of 20 megaHertz to manipulate fluids, droplets and particles in nanoslits that are 50 to 250 nanometers tall. To fill the channels, researchers applied the acoustic waves in the same direction as the fluid moving into the channels. To drain the channels, the sound waves were applied in the opposite direction.

By changing the height of the channels, the device could be used to filter a wide range of particles, down to large biomolecules such as siRNA, which would not fit in the slits. Essentially, the acoustic waves would drive fluids containing the particles into these channels. But while the fluid would go through, the particles would be left behind and form a dry mass. This could be used for rapid diagnosis in the field.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Acoustic Nanofluidics via Room-Temperature Lithium Niobate Bonding: A Platform for Actuation and Manipulation of Nanoconfined Fluids and Particles by Morteza Miansari and James R. Friend. Advanced Functional Materials DOI: 10.1002/adfm.201602425 Version of Record online: 20 SEP 2016

© 2016 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim

This paper is behind a paywall.

They do have an animation sequence illustrating the work but it could be considered suggestive and is, weirdly, silent,