Wednesday, Oct. 5, 2016 was the day three scientists received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work on molecular machines, according to an Oct. 5, 2016 news item on phys.org,

Three scientists won the Nobel Prize in chemistry on Wednesday [Oct. 5, 2016] for developing the world’s smallest machines, 1,000 times thinner than a human hair but with the potential to revolutionize computer and energy systems.

Frenchman Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Scottish-born Fraser Stoddart and Dutch scientist Bernard “Ben” Feringa share the 8 million kronor ($930,000) prize for the “design and synthesis of molecular machines,” the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said.

Machines at the molecular level have taken chemistry to a new dimension and “will most likely be used in the development of things such as new materials, sensors and energy storage systems,” the academy said.

Practical applications are still far away—the academy said molecular motors are at the same stage that electrical motors were in the first half of the 19th century—but the potential is huge.

Dexter Johnson in an Oct. 5, 2016 posting on his Nanoclast blog (on the IEEE [Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers] website) provides some insight into the matter (Note: A link has been removed),

In what seems to have come both as a shock to some of the recipients and a confirmation to all those who envision molecular nanotechnology as the true future of nanotechnology, Bernard Feringa, Jean-Pierre Sauvage, and Sir J. Fraser Stoddart have been awarded the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their development of molecular machines.

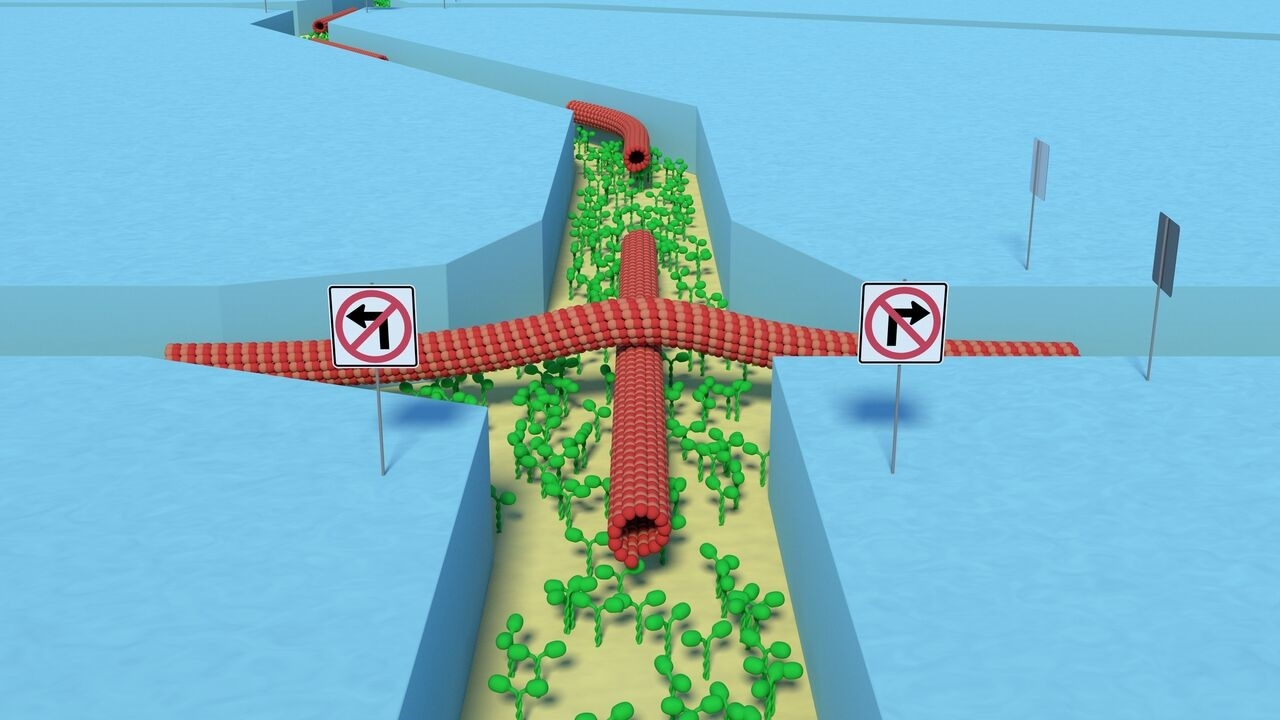

The Nobel Prize was awarded to all three of the scientists based on their complementary work over nearly three decades. First, in 1983, Sauvage (currently at Strasbourg University in France) was able to link two ring-shaped molecules to form a chain. Then, eight years later, Stoddart, a professor at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., demonstrated that a molecular ring could turn on a thin molecular axle. Then, eight years after that, Feringa, a professor at the University of Groningen, in the Netherlands, built on Stoddardt’s work and fabricated a molecular rotor blade that could spin continually in the same direction.

…

Speaking of the Nobel committee’s selection, Donna Nelson, a chemist and president of the American Chemical Society told Scientific American: “I think this topic is going to be fabulous for science. When the Nobel Prize is given, it inspires a lot of interest in the topic by other researchers. It will also increase funding.” Nelson added that this line of research will be fascinating for kids. “They can visualize it, and imagine a nanocar. This comes at a great time, when we need to inspire the next generation of scientists.”

The Economist, which appears to be previewing an article about the 2016 Nobel prizes ahead of the print version, has this to say in its Oct. 8, 2016 article,

BIGGER is not always better. Anyone who doubts that has only to look at the explosion of computing power which has marked the past half-century. This was made possible by continual shrinkage of the components computers are made from. That success has, in turn, inspired a search for other areas where shrinkage might also yield dividends.

One such, which has been poised delicately between hype and hope since the 1990s, is nanotechnology. What people mean by this term has varied over the years—to the extent that cynics might be forgiven for wondering if it is more than just a fancy rebranding of the word “chemistry”—but nanotechnology did originally have a fairly clear definition. It was the idea that machines with moving parts could be made on a molecular scale. And in recognition of this goal Sweden’s Royal Academy of Science this week decided to award this year’s Nobel prize for chemistry to three researchers, Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Sir Fraser Stoddart and Bernard Feringa, who have never lost sight of nanotechnology’s original objective.

…

…

Optimists talk of manufacturing molecule-sized machines ranging from drug-delivery devices to miniature computers. Pessimists recall that nanotechnology is a field that has been puffed up repeatedly by both researchers and investors, only to deflate in the face of practical difficulties.

There is, though, reason to hope it will work in the end. This is because, as is often the case with human inventions, Mother Nature has got there first. One way to think of living cells is as assemblies of nanotechnological machines. For example, the enzyme that produces adenosine triphosphate (ATP)—a molecule used in almost all living cells to fuel biochemical reactions—includes a spinning molecular machine rather like Dr Feringa’s invention. This works well. The ATP generators in a human body turn out so much of the stuff that over the course of a day they create almost a body-weight’s-worth of it. Do something equivalent commercially, and the hype around nanotechnology might prove itself justified.

Congratulations to the three winners!