Science keeps moving. First, there was the June 2022 news and, then, there was the August 2022 news.

A June 8, 2022 Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) press release (also on EurekAlert but published June 7, 2022 as an ‘article highlight’) announces more research into structural colour along with some colour theory from Erwin Schrödinger,

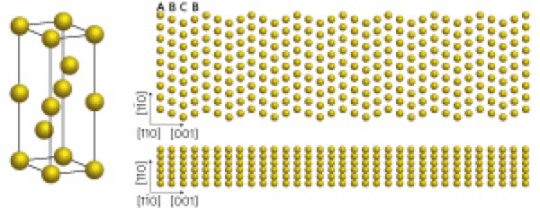

The brilliant and often iridescent colours that we see in some species of birds, beetles and butterflies arise from a regular arrangement of nanostructures that scatter selective wavelengths of light more strongly to generate colour. These colours are called structural colours, which usually range from blues to greens, and even magenta. However, vibrant or saturated reds are elusive and notably absent from the structural colour range in both natural and synthetic realms.

To achieve highly saturated reds, the material needs to absorb light from all wavelengths shorter than ~600 nm and reflect the remaining longer wavelengths, doing both as completely as possible. This sharp transition from absorption to reflection was prescribed theoretically by none other than Erwin Schrödinger of quantum theory fame. However, the physics of resonators tell us that high-order optical resonances in blue will also occur as soon as we have a fundamental resonance in red. This combination of blue and red thus results in the magenta observed in nature. It is therefore challenging to achieve the Schrödinger’s red pixel, which would produce the most saturated red in the world. Current nanoantenna-based approaches are insufficient to simultaneously satisfy the above conditions.

Researchers from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research’s (A*STAR) Institute of Materials Research and Engineering (IMRE), National University of Singapore (NUS) and Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) have collaborated to design and realise reds at the ultimate limit of saturation as predicted by theory, where the team worked together on conceptualisation methodology, fabrications, characterisations and simulations. This research was published in Science Advances on 23 February 2022.

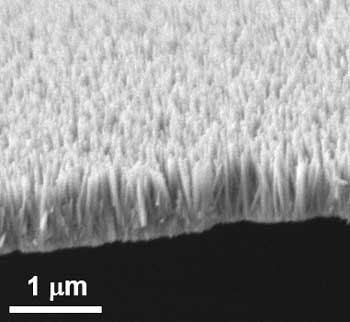

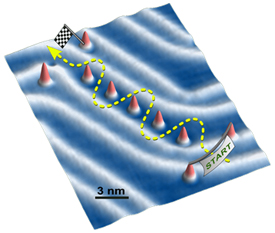

The design consists of regularly arranged silicon nanoantennas in the shape of ellipses. These produce possibly the most saturated and brightest reds with ~80% reflectance, exceeding the reds in the standard red, green and blue gamut (sRGB) and other well-known red pigments, e.g. cadmium red … .

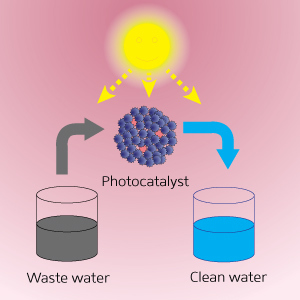

The nanoantennas support two partially overlapping quasi bound-states-in-the-continuum modes, where the optimal dimensions of the silicon nanoantenna arrays are derived by using a gradient descent algorithm to enable the antennas to achieve sharp spectral edges at red wavelengths. At the same time, high-order modes at blue or green wavelengths are suppressed via engineering the substrate‑induced diffraction channels and the absorption of amorphous silicon.Potential uses for Schrödinger’s red include developing a polarisation dependent encryption method, with plans to scale up the Schrödinger’s red pixel for applications like functional nanofabrication devices such as optical spectrometers and reflective displays with high colour saturation.

“With this new design that can achieve the most saturated and brightest reds, we can exploit its sensitivity to polarisation and illumination angle on potential applications for information encryption. This proposed concept and design methodology could also be generalised to other Schrödinger’s colour pixels. The highly-saturated red achieved could be potentially scaled up through methods such as deep ultraviolet and nano-imprint lithography, to reach the dimensions of reflective displays based on multilayer film configuration, which could lead to potential applications like compact red filters, highly saturated reflective displays, nonlocal metasurfaces, and miniaturised spectrometers”, said Dr. Dong Zhaogang, Deputy Department Head of Nanofabrication at A*STAR’s IMRE.

“The creation of the record-high saturation and brightness in red opens up possibilities for a plethora of applications related to anti-counterfeiting technologies, high-calibre colour display and more, which were previously perceived as unachievable with structural colour. It showcases a wonderful synergy between conceptual breakthrough, powerful algorithm and advanced nanofabrication”, said Prof. Cheng-Wei Qiu, Dean’s Chair Professor at NUS.

“This work in structural colours goes to show that we can sometimes outdo evolution through clever use of the tools in nanofabrication and accurate optical simulations”, said Prof. Joel Yang, Provost Chair Professor and Associate Professor in Engineering Product Development at SUTD.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Schrödinger’s red pixel by quasi-bound-states-in-the-continuum by Zhaogang Dong, Lei Jin, Soroosh Daqiqeh Rezaei, Hao Wang, Yang Chen, Febiana Tjiptoharsono, Jinfa Ho, Sergey Gorelik, Ray Jia Hong Ng, Qifeng Ruan, Cheng-Wei Qiu and Joel K. W. Yang. Science Advances Vol 8, Issue 8 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abm4512 Published 23 Feb 2022

This paper is open access.

Math error, colour theory, and perception

An August 10, 2022 news item on phys.org announced a math error made by Erwin Schrödinger and others,

A new study corrects an important error in the 3D mathematical space developed by the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Erwin Schrödinger and others, and used by scientists and industry for more than 100 years to describe how your eye distinguishes one color from another. The research has the potential to boost scientific data visualizations, improve TVs and recalibrate the textile and paint industries.

“The assumed shape of color space requires a paradigm shift,” said Roxana Bujack, a computer scientist with a background in mathematics who creates scientific visualizations at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Bujack is lead author of the paper by a Los Alamos team in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on the mathematics of color perception.

“Our research shows that the current mathematical model of how the eye perceives color differences is incorrect. That model was suggested by Bernhard Riemann and developed by Hermann von Helmholtz and Erwin Schrödinger—all giants in mathematics and physics—and proving one of them wrong is pretty much the dream of a scientist,” said Bujack.

…

While the Los Alamos National Laboratory work was published in April 2022 (online) and May 2022 (in print), their news announcement doesn’t seem to have been made until August. I can’t be certain but I believe this should have an impact on the work from A*STAR as that team’s paper cites: E. Schrödinger, Theorie der Pigmente von größter Leuchtkraft. Ann. Phys. 367, 603–622 (1920).

An August 10, 2022 Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) news release (also on EurekAlert) provides more information about the discovery,

Modeling human color perception enables automation of image processing, computer graphics and visualization tasks.

“Our original idea was to develop algorithms to automatically improve color maps for data visualization, to make them easier to understand and interpret,” Bujack said. So the team was surprised when they discovered they were the first to determine that the longstanding application of Riemannian geometry, which allows generalizing straight lines to curved surfaces, didn’t work.

To create industry standards, a precise mathematical model of perceived color space is needed. First attempts used Euclidean spaces—the familiar geometry taught in many high schools; more advanced models used Riemannian geometry. The models plot red, green and blue in the 3D space. Those are the colors registered most strongly by light-detecting cones on our retinas, and—not surprisingly—the colors that blend to create all the images on your RGB computer screen.

In the study, which blends psychology, biology and mathematics, Bujack and her colleagues discovered that using Riemannian geometry overestimates the perception of large color differences. That’s because people perceive a big difference in color to be less than the sum you would get if you added up small differences in color that lie between two widely separated shades.

Riemannian geometry cannot account for this effect.

“We didn’t expect this, and we don’t know the exact geometry of this new color space yet,” Bujack said. “We might be able to think of it normally but with an added dampening or weighing function that pulls long distances in, making them shorter. But we can’t prove it yet.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

The non-Riemannian nature of perceptual color space by Roxana Bujack, Emily Teti, Jonah Miller, Elektra Caffrey, and Terece L. Turton. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 119 (18) e2119753119 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2119753119 Published: April 29, 2022

This paper is behind a paywall.

![[downloaded from http://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/la4034996]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/WaterPinningRosePetals-300x153.gif)