Scientists have come to a better understanding of the mechanism affecting silver nanoparticle toxicity according to an Aug. 30, 2016 news item on Nanowerk (Note: A link has been removed),

A senior fellow at the Faculty of Chemistry, MSU (Lomonosov Moscow State University), Vladimir Bochenkov together with his colleagues from Denmark succeeded in deciphering the mechanism of interaction of silver nanoparticles with the cells of the immune system. The study is published in the journal Nature Communications (“Dynamic protein coronas revealed as a modulator of silver nanoparticle sulphidation in vitro”).

‘Currently, a large number of products are containing silver nanoparticles: antibacterial drugs, toothpaste, polishes, paints, filters, packaging, medical and textile items. The functioning of these products lies in the capacity of silver to dissolve under oxidation and form ions Ag+ with germicidal properties. At the same time there are research data in vitro, showing the silver nanoparticles toxicity for various organs, including the liver, brain and lungs. In this regard, it is essential to study the processes occurring with silver nanoparticles in biological environments, and the factors affecting their toxicity,’ says Vladimir Bochenkov.

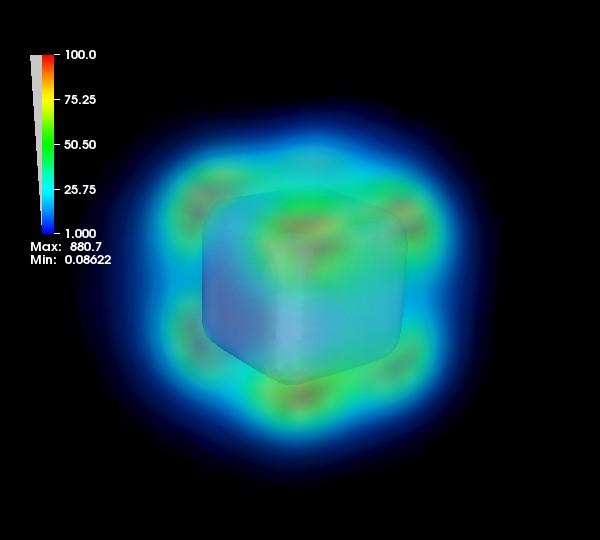

Caption: Increased intensity of the electric field near the silver nanoparticle surface in the excitation of plasmon resonance. Credit: Vladimir Bochenkov

An Aug. 30, 2016 MSU press release on EurekAlert, which originated the news item, provides more information about the research,

The study is devoted to the protein corona — a layer of adsorbed protein molecules, which is formed on the surface of the silver nanoparticles during their contact with the biological environment, for example in blood. Protein crown masks nanoparticles and largely determines their fate: the speed of the elimination from the body, the ability to penetrate to a particular cell type, the distribution between the organs, etc.

According to the latest research, the protein corona consists of two layers: a rigid hard corona — protein molecules tightly bound with silver nanoparticles, and soft corona, consisting of weakly bound protein molecules in a dynamic equilibrium with the solution. Hitherto soft corona has been studied very little because of the experimental difficulties: the weakly bound nanoparticles separated from the protein solution easily desorbed (leave a particle remaining in the solution), leaving only the rigid corona on the nanoparticle surface.

The size of the studied silver nanoparticles was of 50-88 nm, and the diameter of the proteins that made up the crown — 3-7 nm. Scientists managed to study the silver nanoparticles with the protein corona in situ, not removing them from the biological environment. Due to the localized surface plasmon resonance used for probing the environment near the surface of the silver nanoparticles, the functions of the soft corona have been primarily investigated.

‘In the work we showed that the corona may affect the ability of the nanoparticles to dissolve to silver cations Ag+, which determine the toxic effect. In the absence of a soft corona (quickly sharing the medium protein layer with the environment) silver cations are associated with the sulfur-containing amino acids in serum medium, particularly cysteine and methionine, and precipitate as nanocrystals Ag2S in the hard corona,’ says Vladimir Bochenkov.

Ag2S (silver sulfide) famously easily forms on the silver surface even on the air in the presence of the hydrogen sulfide traces. Sulfur is also part of many biomolecules contained in the body, provoking the silver to react and be converted into sulfide. Forming of the nano-crystals Ag2S due to low solubility reduces the bioavailability of the Ag+ ions, reducing the toxicity of silver nanoparticles to null. With a sufficient amount of amino acid sulfur sources available for reaction, all the potentially toxic silver is converted into the nontoxic insoluble sulfide. Scientists have shown that what happens in the absence of a soft corona.

In the presence of a soft corona, the Ag2S silver sulfide nanocrystals are formed in smaller quantities or not formed at all. Scientists attribute this to the fact that the weakly bound protein molecules transfer the Ag+ ions from nanoparticles into the solution, thereby leaving the sulfide not crystallized. Thus, the soft corona proteins are ‘vehicles’ for the silver ions.

This effect, scientists believe, be taken into account when analyzing the stability of silver nanoparticles in a protein environment, and in interpreting the results of the toxicity studies. Studies of the cells viability of the immune system (J774 murine line macrophages) confirmed the reduction in cell toxicity of silver nanoparticles at the sulfidation (in the absence of a soft corona).

Vladimir Bochenkov’s challenge was to simulate the plasmon resonance spectra of the studied systems and to create the theoretical model that allowed quantitative determination of silver sulfide content in situ around nanoparticles, following the change in the absorption bands in the experimental spectra. Since the frequency of the plasmon resonance is sensitive to a change in dielectric constant near the nanoparticle surface, changes in the absorption spectra contain information about the amount of silver sulfide formed.

Knowledge of the mechanisms of formation and dynamics of the behavior of the protein corona, information about its composition and structure are extremely important for understanding the toxicity and hazards of nanoparticles for the human body. In prospect the protein corona formation can be used to deliver drugs in the body, including the treatment of cancer. For this purpose it will be enough to pick such a content of the protein corona, which enables silver nanoparticles penetrate only in the cancer cell and kill it.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper describing this fascinating work,

Dynamic protein coronas revealed as a modulator of silver nanoparticle sulphidation in vitro by Teodora Miclăuş, Christiane Beer, Jacques Chevallier, Carsten Scavenius, Vladimir E. Bochenkov, Jan J. Enghild, & Duncan S. Sutherland. Nature Communications 7,

Article number: 11770 doi:10.1038/ncomms11770 Published 09 June 2016

This paper is open access.

![Fig. 1: A Vigna radiata seeds. b Reddish brown solution of silver nanoparticles formed after 3 h due to reduction of silver ions [downloaded from http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13204-015-0418-6]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/India_SilverNanoparrticles_MungBean.gif)