I’ve never seen an educational institution use a somewhat vulgar slang term such as ‘puke’ before. Especially not in a news release. You’ll find that elsewhere online ‘puke’ has been replaced, in the headline, with the more socially acceptable ‘vomit’.

Since I wanted to catch this historic moment amid concerns that the original version of the news release will disappear, I’m including the entire news release as i saw it on EurekAlert.com (from an October 2, 2019 University of California at Berkeley news release),

News Release 2-Oct-2019

CRISPRed fruit flies mimic monarch butterfly — and could make you puke

Scientists recreate in flies the mutations that let monarch butterfly eat toxic milkweed with impunityUniversity of California – Berkeley

The fruit flies in Noah Whiteman’s lab may be hazardous to your health.

Whiteman and his University of California, Berkeley, colleagues have turned perfectly palatable fruit flies — palatable, at least, to frogs and birds — into potentially poisonous prey that may cause anything that eats them to puke. In large enough quantities, the flies likely would make a human puke, too, much like the emetic effect of ipecac syrup.

That’s because the team genetically engineered the flies, using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, to be able to eat milkweed without dying and to sequester its toxins, just as America’s most beloved butterfly, the monarch, does to deter predators.

This is the first time anyone has recreated in a multicellular organism a set of evolutionary mutations leading to a totally new adaptation to the environment — in this case, a new diet and new way of deterring predators.

Like monarch caterpillars, the CRISPRed fruit fly maggots thrive on milkweed, which contains toxins that kill most other animals, humans included. The maggots store the toxins in their bodies and retain them through metamorphosis, after they turn into adult flies, which means the adult “monarch flies” could also make animals upchuck.

The team achieved this feat by making three CRISPR edits in a single gene: modifications identical to the genetic mutations that allow monarch butterflies to dine on milkweed and sequester its poison. These mutations in the monarch have allowed it to eat common poisonous plants other insects could not and are key to the butterfly’s thriving presence throughout North and Central America.

Flies with the triple genetic mutation proved to be 1,000 times less sensitive to milkweed toxin than the wild fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster.

Whiteman and his colleagues will describe their experiment in the Oct. 2 [2019] issue of the journal Nature.

Monarch flies

The UC Berkeley researchers created these monarch flies to establish, beyond a shadow of a doubt, which genetic changes in the genome of monarch butterflies were necessary to allow them to eat milkweed with impunity. They found, surprisingly, that only three single-nucleotide substitutions in one gene are sufficient to give fruit flies the same toxin resistance as monarchs.

“All we did was change three sites, and we made these superflies,” said Whiteman, an associate professor of integrative biology. “But to me, the most amazing thing is that we were able to test evolutionary hypotheses in a way that has never been possible outside of cell lines. It would have been difficult to discover this without having the ability to create mutations with CRISPR.”

Whiteman’s team also showed that 20 other insect groups able to eat milkweed and related toxic plants – including moths, beetles, wasps, flies, aphids, a weevil and a true bug, most of which sport the color orange to warn away predators – independently evolved mutations in one, two or three of the same amino acid positions to overcome, to varying degrees, the toxic effects of these plant poisons.

In fact, his team reconstructed the one, two or three mutations that led to each of the four butterfly and moth lineages, each mutation conferring some resistance to the toxin. All three mutations were necessary to make the monarch butterfly the king of milkweed.

Resistance to milkweed toxin comes at a cost, however. Monarch flies are not as quick to recover from upsets, such as being shaken — a test known as “bang” sensitivity.“This shows there is a cost to mutations, in terms of recovery of the nervous system and probably other things we don’t know about,” Whiteman said. “But the benefit of being able to escape a predator is so high … if it’s death or toxins, toxins will win, even if there is a cost.”

Plant vs. insect

Whiteman is interested in the evolutionary battle between plants and parasites and was intrigued by the evolutionary adaptations that allowed the monarch to beat the milkweed’s toxic defense. He also wanted to know whether other insects that are resistant — though all less resistant than the monarch — use similar tricks to disable the toxin.

“Since plants and animals first invaded land 400 million years ago, this coevolutionary arms race is thought to have given rise to a lot of the plant and animal diversity that we see, because most animals are insects, and most insects are herbivorous: they eat plants,” he said.

Milkweeds and a variety of other plants, including foxglove, the source of digitoxin and digoxin, contain related toxins — called cardiac glycosides — that can kill an elephant and any creature with a beating heart. Foxglove’s effect on the heart is the reason that an extract of the plant, in the genus Digitalis, has been used for centuries to treat heart conditions, and why digoxin and digitoxin are used today to treat congestive heart failure.

These plants’ bitterness alone is enough to deter most animals, but a small minority of insects, including the monarch (Danaus plexippus) and its relative, the queen butterfly (Danaus gilippus), have learned to love milkweed and use it to repel predators.

Whiteman noted that the monarch is a tropical lineage that invaded North America after the last ice age, in part enabled by the three mutations that allowed it to eat a poisonous plant other animals could not, giving it a survival edge and a natural defense against predators.

“The monarch resists the toxin the best of all the insects, and it has the biggest population size of any of them; it’s all over the world,” he said.

The new paper reveals that the mutations had to occur in the right sequence, or else the flies would never have survived the three separate mutational events.

Thwarting the sodium pump

The poisons in these plants, most of them a type of cardenolide, interfere with the sodium/potassium pump (Na+/K+-ATPase) that most of the body’s cells use to move sodium ions out and potassium ions in. The pump creates an ion imbalance that the cell uses to its favor. Nerve cells, for example, transmit signals along their elongated cell bodies, or axons, by opening sodium and potassium gates in a wave that moves down the axon, allowing ions to flow in and out to equilibrate the imbalance. After the wave passes, the sodium pump re-establishes the ionic imbalance.

Digitoxin, from foxglove, and ouabain, the main toxin in milkweed, block the pump and prevent the cell from establishing the sodium/potassium gradient. This throws the ion concentration in the cell out of whack, causing all sorts of problems. In animals with hearts, like birds and humans, heart cells begin to beat so strongly that the heart fails; the result is death by cardiac arrest.

Scientists have known for decades how these toxins interact with the sodium pump: they bind the part of the pump protein that sticks out through the cell membrane, clogging the channel. They’ve even identified two specific amino acid changes or mutations in the protein pump that monarchs and the other insects evolved to prevent the toxin from binding.

But Whiteman and his colleagues weren’t satisfied with this just so explanation: that insects coincidentally developed the same two identical mutations in the sodium pump 14 separate times, end of story. With the advent of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing in 2012, coinvented by UC Berkeley’s Jennifer Doudna, Whiteman and colleagues Anurag Agrawal of Cornell University and Susanne Dobler of the University of Hamburg in Germany applied to the Templeton Foundation for a grant to recreate these mutations in fruit flies and to see if they could make the flies immune to the toxic effects of cardenolides.

Seven years, many failed attempts and one new grant from the National Institutes of Health later, along with the dedicated CRISPR work of GenetiVision of Houston, Texas, they finally achieved their goal. In the process, they discovered a third critical, compensatory mutation in the sodium pump that had to occur before the last and most potent resistance mutation would stick. Without this compensatory mutation, the maggots died.

Their detective work required inserting single, double and triple mutations into the fruit fly’s own sodium pump gene, in various orders, to assess which ones were necessary. Insects having only one of the two known amino acid changes in the sodium pump gene were best at resisting the plant poisons, but they also had serious side effects — nervous system problems — consistent with the fact that sodium pump mutations in humans are often associated with seizures. However, the third, compensatory mutation somehow reduces the negative effects of the other two mutations.

“One substitution that evolved confers weak resistance, but it is always present and allows for substitutions that are going to confer the most resistance,” said postdoctoral fellow Marianna Karageorgi, a geneticist and evolutionary biologist. “This substitution in the insect unlocks the resistance substitutions, reducing the neurological costs of resistance. Because this trait has evolved so many times, we have also shown that this is not random.”

The fact that one compensatory mutation is required before insects with the most resistant mutation could survive placed a constraint on how insects could evolve toxin resistance, explaining why all 21 lineages converged on the same solution, Whiteman said. In other situations, such as where the protein involved is not so critical to survival, animals might find different solutions.

“This helps answer the question, ‘Why does convergence evolve sometimes, but not other times?'” Whiteman said. “Maybe the constraints vary. That’s a simple answer, but if you think about it, these three mutations turned a Drosophila protein into a monarch one, with respect to cardenolide resistance. That’s kind of remarkable.”

###

The research was funded by the Templeton Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. Co-authors with Whiteman and Agrawal are co-first authors Marianthi Karageorgi of UC Berkeley and Simon Groen, now at New York University; Fidan Sumbul and Felix Rico of Aix-Marseille Université in France; Julianne Pelaez, Kirsten Verster, Jessica Aguilar, Susan Bernstein, Teruyuki Matsunaga and Michael Astourian of UC Berkeley; Amy Hastings of Cornell; and Susanne Dobler of Universität Hamburg in Germany.

Robert Sanders’ Oct. 2, 2019′ news release for the University of California at Berkeley (it’s also been republished as an Oct. 2, 2019 news item on ScienceDaily) has had its headline changed to ‘vomit’ but you’ll find the more vulgar word remains in two locations of the second paragraph of the revised new release.

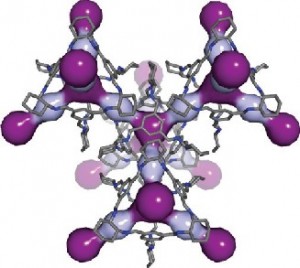

If you have time, go to the news release on the University of California at Berkeley website just to admire the images that have been embedded in the news release. Here’s one,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Genome editing retraces the evolution of toxin resistance in the monarch butterfly by Marianthi Karageorgi, Simon C. Groen, Fidan Sumbul, Julianne N. Pelaez, Kirsten I. Verster, Jessica M. Aguilar, Amy P. Hastings, Susan L. Bernstein, Teruyuki Matsunaga, Michael Astourian, Geno Guerra, Felix Rico, Susanne Dobler, Anurag A. Agrawal & Noah K. Whiteman. Nature (2019) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1610-8 Published 02 October 2019

This paper is behind a paywall.

Words about a word

I’m glad they changed the headline and substituted vomit for puke. I think we need vulgar and/or taboo words to release anger or disgust or other difficult emotions. Incorporating those words into standard language deprives them of that power.

The last word: Genetivision

The company mentioned in the new release, Genetivision, is the place to go for transgenic flies. Here’s a sampling from the their Testimonials webpage,

“GenetiVision‘s service has been excellent in the quality and price. The timeliness of its international service has been a big plus. We are very happy with its consistent service and the flies it generates.”

Kwang-Wook Choi, Ph.D.

Department of Biological Sciences

Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology

“We couldn’t be happier with GenetiVision. Great prices on both standard P and PhiC31 transgenics, quick turnaround time, and we’re still batting 1000 with transformant success. We used to do our own injections but your service makes it both faster and more cost-effective. Thanks for your service!”

Thomas Neufeld, Ph.D.

Department of Genetics, Cell Biology and Development

University of Minnesota

You can find out more here at the Genetivision website.