Heat is always a problem with electronics—even nanoelectronics. Scientists at Rice University (US) believe they may have a solution for nanoelectronics heat problems, according to a Jan. 4, 2017 news item on ScienceDaily,

A few nanoscale adjustments may be all that is required to make graphene-nanotube junctions excel at transferring heat, according to Rice University scientists.

The Rice lab of theoretical physicist Boris Yakobson found that putting a cone-like “chimney” between the graphene and [carbon] nanotube all but eliminates a barrier that blocks heat from escaping.

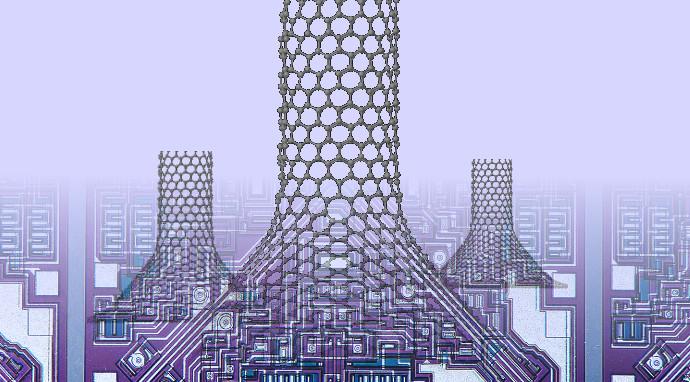

Caption: Simulations by Rice University scientists show that placing cones between graphene and carbon nanotubes could enhance heat dissipation from nano-electronics. The nano-chimneys become better at conducting heat-carrying phonons by spreading out the number of heptagons required by the graphene-to-nanotube transition. Credit: Alex Kutana/Rice University

A Jan. 4, 2016 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes the research in more detail,

Heat is transferred through phonons, quasiparticle waves that also transmit sound. The Rice theory offers a strategy to channel damaging heat away from next-generation nano-electronics.

Both graphene and carbon nanotubes consist of six-atom rings, which create a chicken-wire appearance, and both excel at the rapid transfer of electricity and phonons.

But when a nanotube grows from graphene, atoms facilitate the turn by forming heptagonal (seven-member) rings instead. Scientists have determined that forests of nanotubes grown from graphene are excellent for storing hydrogen for energy applications, but in electronics, the heptagons scatter phonons and hinder the escape of heat through the pillars.

The Rice researchers discovered through computer simulations that removing atoms here and there from the two-dimensional graphene base would force a cone to form between the graphene and the nanotube. The geometric properties (aka topology) of the graphene-to-cone and cone-to-nanotube transitions require the same total number of heptagons, but they are more sparsely spaced and leave a clear path of hexagons available for heat to race up the chimney.

“Our interest in advancing new applications for low-dimensional carbon — fullerenes, nanotubes and graphene — is broad,” Yakobson said. “One way is to use them as building blocks to fill three-dimensional spaces with different designs, creating anisotropic, nonuniform scaffolds with properties that none of the current bulk materials have. In this case, we studied a combination of nanotubes and graphene, connected by cones, motivated by seeing such shapes obtained in our colleagues’ experimental labs.”

The researchers tested phonon conduction through simulations of free-standing nanotubes, pillared graphene and nano-chimneys with a cone radius of either 20 or 40 angstroms. The pillared graphene was 20 percent less conductive than plain nanotubes. The 20-angstrom nano-chimneys were just as conductive as plain nanotubes, while 40-angstrom cones were 20 percent better than the nanotubes.

“The tunability of such structures is virtually limitless, stemming from the vast combinatorial possibilities of arranging the elementary modules,” said Alex Kutana, a Rice research scientist and co-author of the study. “The actual challenge is to find the most useful structures given a vast number of possibilities and then make them in the lab reliably.

“In the present case, the fine-tuning parameters could be cone shapes and radii, nanotube spacing, lengths and diameters. Interestingly, the nano-chimneys also act like thermal diodes, with heat flowing faster in one direction than the other,” he said.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Nanochimneys: Topology and Thermal Conductance of 3D Nanotube–Graphene Cone Junctions by Ziang Zhang, Alex Kutana, Ajit Roy, and Boris I. Yakobson. J. Phys. Chem. C, Article ASAP DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b11350 Publication Date (Web): December 21, 2016

Copyright © 2016 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.