Here’s what you’re seeing (from the YouTube entry),

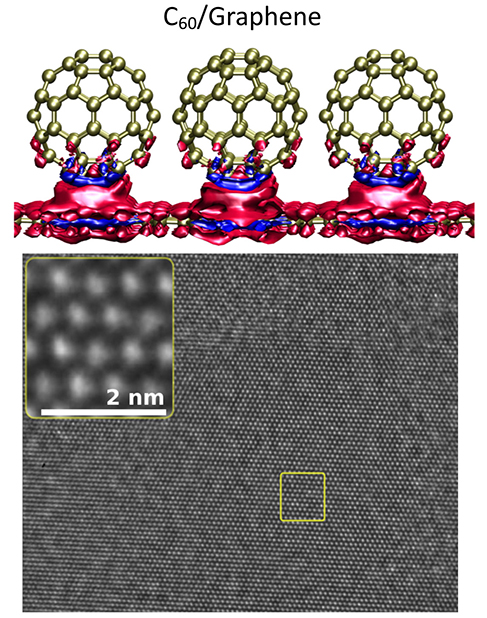

Berkeley Lab scientists and collaborators took advantage of one of the best microscopes in the world – the TEAM I electron microscope at the Molecular Foundry – to watch how individual gold atoms organized themselves into crystals on top of graphene. The research team observed as groups of gold atoms formed and broke apart many times, trying out different configurations, before finally stabilizing. The discovery of this fast-changing and reversible process was possible thanks to these high-speed images captured at atomic resolution. Credit: Berkeley Lab

The work was announced in a March 25, 2021 news item on phys.org,

When we grow crystals, atoms first group together into small clusters—a process called nucleation. But understanding exactly how such atomic ordering emerges from the chaos of randomly moving atoms has long eluded scientists.

Classical nucleation theory suggests that crystals form one atom at a time, steadily increasing the level of order. Modern studies have also observed a two-step nucleation process, where a temporary, high-energy structure forms first, which then changes into a stable crystal. But according to an international research team co-led by the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), the real story is even more complicated.

Their findings, recently reported in the journal Science, reveal that rather than grouping together one-by-one or making a single irreversible transition, gold atoms will instead self-organize, fall apart, regroup, and then reorganize many times before establishing a stable, ordered crystal. Using an advanced electron microscope, the researchers witnessed this rapid, reversible nucleation process for the first time. Their work provides tangible insights into the early stages of many growth processes such as thin-film deposition and nanoparticle formation.

…

A March 25, 2021 DOE [US Dept. of Energy]/Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory news release (also on EurekAlert) by Clarissa Bhargava, which originated the news item, expands on the topic,

“As scientists seek to control matter at smaller length scales to produce new materials and devices, this study helps us understand exactly how some crystals form,” said Peter Ercius, one of the study’s lead authors and a staff scientist at Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry.

In line with scientists’ conventional understanding, once the crystals in the study reached a certain size, they no longer returned to the disordered, unstable state. Won Chul Lee, one of the professors guiding the project, describes it this way: if we imagine each atom as a Lego brick, then instead of building a house one brick at a time, it turns out that the bricks repeatedly fit together and break apart again until they are finally strong enough to stay together. Once the foundation is set, however, more bricks can be added without disrupting the overall structure.

The unstable structures were only visible because of the speed of newly developed detectors on the TEAM I [Transmission Electron Aberration-corrected Microscope], one of the world’s most powerful electron microscopes. A team of in-house experts guided the experiments at the National Center for Electron Microscopy in Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry. Using the TEAM I microscope, researchers captured real-time, atomic-resolution images at speeds up to 625 frames per second, which is exceptionally fast for electron microcopy and about 100 times faster than previous studies. The researchers observed individual gold atoms as they formed into crystals, broke apart into individual atoms, and then reformed again and again into different crystal configurations before finally stabilizing.

“Slower observations would miss this very fast, reversible process and just see a blur instead of the transitions, which explains why this nucleation behavior has never been seen before,” said Ercius.

The reason behind this reversible phenomenon is that crystal formation is an exothermic process – that is, it releases energy. In fact, the very energy released when atoms attach to the tiny nuclei can raise the local “temperature” and melt the crystal. In this way, the initial crystal formation process works against itself, fluctuating between order and disorder many times before building a nucleus that is stable enough to withstand the heat. The research team validated this interpretation of their experimental observations by performing calculations of binding reactions between a hypothetical gold atom and a nanocrystal.

Now, scientists are developing even faster detectors which could be used to image the process at higher speeds. This could help them understand if there are more features of nucleation hidden in the atomic chaos. The team is also hoping to spot similar transitions in different atomic systems to determine whether this discovery reflects a general process of nucleation.

One of the study’s lead authors, Jungwon Park, summarized the work: “From a scientific point of view, we discovered a new principle of crystal nucleation process, and we proved it experimentally.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Reversible disorder-order transitions in atomic crystal nucleation by Sungho Jeon, Taeyeong Heo, Sang-Yeon Hwang, Jim Ciston, Karen C. Bustillo, Bryan W. Reed, Jimin Ham, Sungsu Kang, Sungin Kim, Joowon Lim, Kitaek Lim, Ji Soo Kim, Min-Ho Kang, Ruth S. Bloom, Sukjoon Hong, Kwanpyo Kim, Alex Zettl, Woo Youn Kim, Peter Ercius, Jungwon Park, Won Chul Lee. Science 29 Jan 2021: Vol. 371, Issue 6528, pp. 498-503 DOI: 10.1126/science.aaz7555

This paper is behind a paywall.