There is a controversy over one of the important pieces (it’s considered foundational) of modern art, “Fountain.” (ETA April 29, 2020: If you have time, please take a look at a rejoinder in the comments, which includes links to material debunking the theory that follows.)

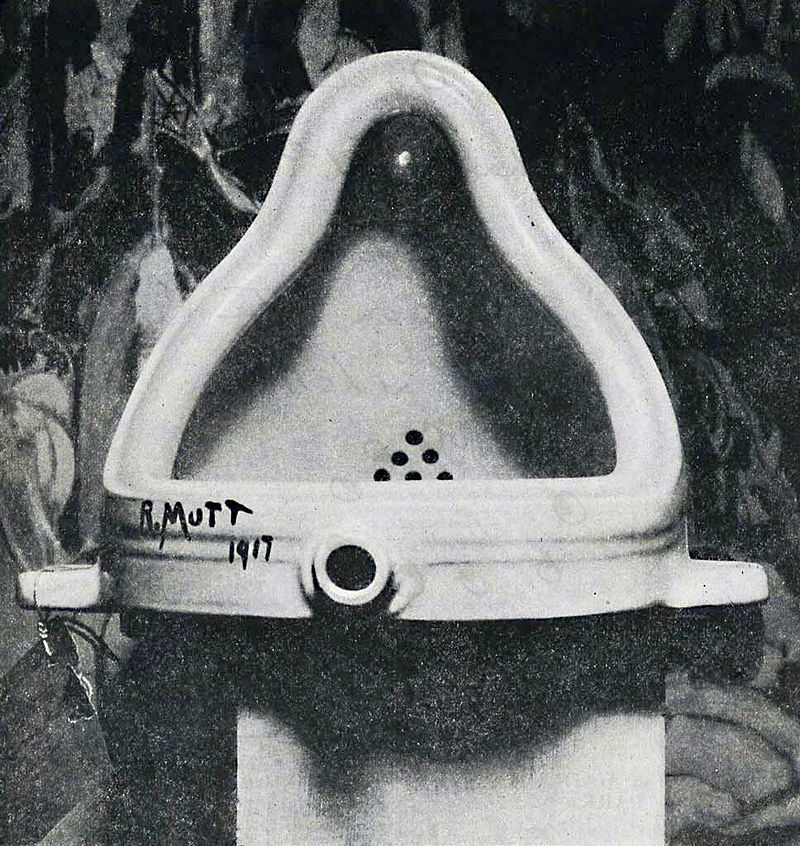

The original Fountain by Marcel Duchamp photographed by Alfred Stieglitz at the 291 (Art Gallery) after the 1917 Society of Independent Artists exhibit. Stieglitz used a backdrop of The Warriors by Marsden Hartley to photograph the urinal. The entry tag is clearly visible. [downloaded from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fountain_%28Duchamp%29

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven the real artist behind the ‘Fountain’

According to Theo Paijmans in his June 2018 article (abstract) on See All This, the correct attribution is not Marcel Duchamp,

In 1917, when the United States was about to enter the First World War and women in the United Kingdom had just earned their right to vote, a different matter occupied the sentiments of the small, modernist art scene in New York. It had organised an exhibit where anyone could show his or her art against a small fee, but someone had sent in a urinal for display. This was against even the most avant-garde taste of the organisers of the exhibit. The urinal, sent in anonymously, without title and only signed with the enigmatic ‘R. Mutt’, quickly vanished from view. Only one photo of the urinal remains.

Theo Paijmans, June 2018

In 1935 famous surrealist artist André Breton attributed the urinal to Marcel Duchamp. Out of this grew the consensus that Duchamp was its creator. Over time Duchamp commissioned a number of replicas of the urinal that now had a name: Fountain – coined by a reviewer who briefly visited the exhibit in 1917. The original urinal had since long disappeared. In all probability it had been unceremoniously dumped on the trash heap, but ironically it was destined to become one of the most iconic works of modern art. In 2004, some five hundred artists and art experts heralded Fountain as the most influential piece of modern art, even leaving Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon behind. Once again it cemented the reputation of Duchamp as one of the towering geniuses in the history of modern art.

But then things took a turn

Portrait of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

In 1982 a letter written by Duchamp came to light. Dated 11 April 1917, it was written just a few days after that fateful exhibit. It contains one sentence that should have sent shockwaves through the world of modern art: it reveals the true creator behind Fountain – but it was not Duchamp. Instead he wrote that a female friend using a male alias had sent it in for the New York exhibition. Suddenly a few other things began to make sense. Over time Duchamp had told two different stories of how he had created Fountain, but both turned out to be untrue. An art historian who knew Duchamp admitted that he had never asked him about Fountain, he had published a standard-work on Fountain nevertheless. The place from where Fountain was sent raised more questions. That place was Philadelphia, but Duchamp had been living in New York.

Female friend

Who was living in Philadelphia? Who was this ‘female friend’ that had sent the urinal using a pseudonym that Duchamp mentions? That woman was, as Duchamp wrote, the future. Art history knows her as Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. She was a brilliant pioneering New York dada artist, and Duchamp knew her well. This glaring truth has been known for some time in the art world, but each time it has to be acknowledged, it is met with indifference and silence.

You have to pay to read the rest but See All This does include a video with the abstract for the article,

You may want to know one other thing, the magazine appears to be available only in Dutch. Taking that into account, here’s a link to the magazine along with some details about the experts who consulted with Paijmans,

This is an abstract from the Dutch article ‘Het urinoir is niet van Duchamp’ that is published in See All This art magazine’s summer issue. For his research, the author interviewed Irene Gammel (biographer of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven and professor at the Ryerson University in Toronto), Glyn Thompson (art historian, curator and writer), Julian Spalding (art critic and former director of Glasgow museums and galleries), and John Higgs (cultural historian and journalist).

The [2018] summer issue of See All This magazine is dedicated to 99 genius women in the art world, to celebrate the voice of women and the 100th anniversary of women’s right to vote in the Netherlands in 2019. Buy this issue online.

It’s certainly a provocative thesis and it seems there’s a fair degree of evidence to support it. Although there is an alternative attribution, also female. From the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven Wikipedia entry (Note: Links have been removed),

In a letter written by Marcel Duchamp to his sister Suzanne dated April 11, 1917 he refers to his famous ready-made, Fountain (1917) and states: “One of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.”[33] Some have claimed that the friend in question was the Baroness, but Francis Naumann, the New York-based critic and expert on Dada who put together a compilation of Duchamp’s letters and organized Making Mischief: Dada Invades New York for the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1997, explains this “female friend” is Louise Norton who contributed an essay to The Blind Man discussing Fountain. Norton was living at 110 West 88th Street in New York City and this address is partially discernible (along with “Richard Mutt”) on the paper entry ticket attached to the object, as seen in Stieglitz’s photograph of Fountain.[emphases mine]

Or is it Louise Norton?

The “Fountain” Wikipedia entry does not clarify matters (Note: Links have been removed),

Marcel Duchamp arrived in the United States less than two years prior to the creation of Fountain and had become involved with Dada, an anti-rational, anti-art cultural movement, in New York City. According to one version, the creation of Fountain began when, accompanied by artist Joseph Stella and art collector Walter Arensberg, he purchased a standard Bedfordshire model urinal from the J. L. Mott Iron Works, 118 Fifth Avenue. The artist brought the urinal to his studio at 33 West 67th Street, reoriented it to a position 90 degrees from its normal position of use, and wrote on it, “R. Mutt 1917”.[3][4]

According to another version, Duchamp did not create Fountain, but rather assisted in submitting the piece to the Society of Independent Artists for a female friend. In a letter dated 11 April 1917 Duchamp wrote to his sister Suzanne telling her about the circumstances around Fountain’s submission: “Une de mes amies sous un pseudonyme masculin, Richard Mutt, avait envoyé une pissotière [urinal] en porcelaine comme sculpture” (“One of my female friends, who had adopted the male pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.”)[5][6] Duchamp never identified his female friend, but two candidates have been proposed: the Dadaist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven[7][8] whose scatological aesthetic echoed that of Duchamp, or Louise Norton, who contributed an essay to The Blind Man discussing Fountain. Norton, who recently had separated from her husband, was living at the time in an apartment owned by her parents at 110 West 88th Street in New York City, and this address is partially discernible (along with “Richard Mutt”) on the paper entry ticket attached to the object, as seen in Stieglitz’s photograph.[9]

Rhonda Roland Shearer in the online journal Tout-Fait (2000) has concluded that the photograph is a composite of different photos, while other scholars such as William Camfield have never been able to match the urinal shown in the photo to any urinals found in the catalogues of the time period.[10] [emphases mine]

Attributing “Fountain” to a woman changes my understanding of the work. It seems to me. After all, it’s a woman submitting a urinal (plumbing designed specifically for the male anatomy) as a work of art.What was she (whichever she) is saying?

It’s tempting to read a commentary on patriarchy and art into the piece but von Freytag-Loringhoven (I’ll get to Norton next) may have had other issues in mind, from her Wikipedia entry (Note: Links have been removed),

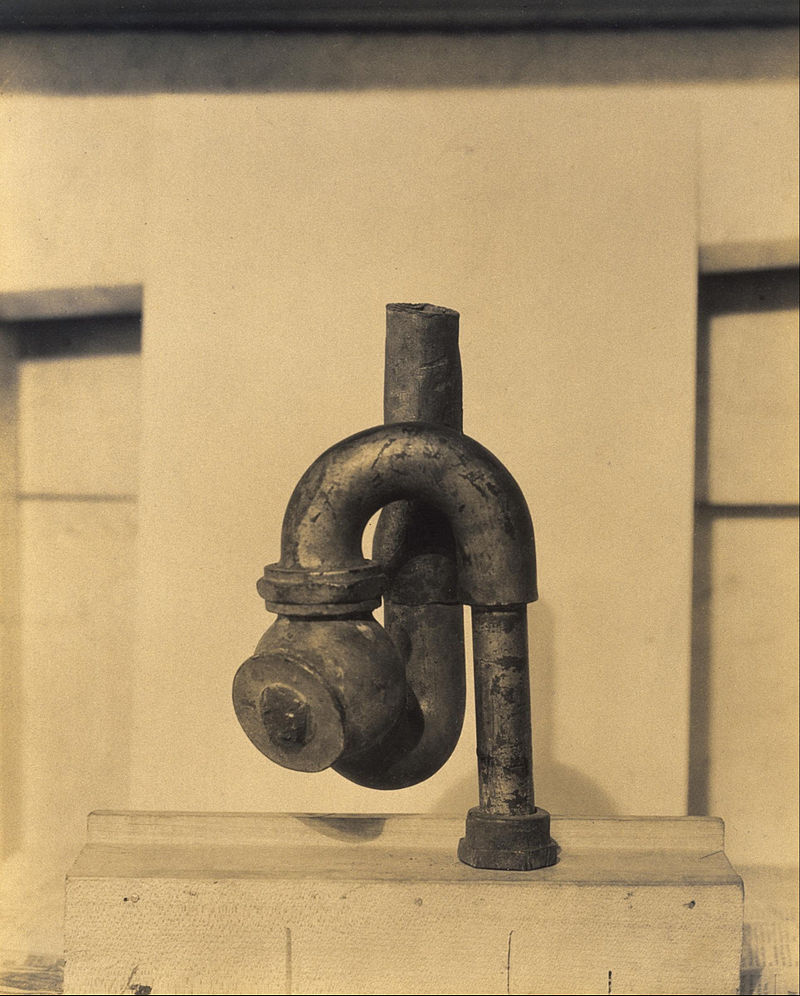

There has been substantial new research indicating that some artworks attributed to other artists of the period can now either be attributed to the Baroness, or raise the possibility that she may have created the works. One work, called God (1917) had for a number of years been attributed to the artist Morton Livingston Schamberg. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, whose collection includes God, now credits the Baroness as a co-artist of this piece. Amelia Jones idenitified that this artwork’s concept and title was created by the Baroness, however, it was constructed by both Shamberg and the Baroness.[30] This sculpture, God (1917), involved a cast iron pumbing trap and a wooden mitre box, assembled in a phallic-like manner. [31] Her concept behind the shape and choice of materials is indicative of her commentary on the worship and love that Americans have for plumbing that trumps all else; additionally, it is revealing of the Baroness’s rejection of technology. [emphases mine]

As for Norton, unfortunately I’m not familiar with her work and this is the only credible reference to her that I’ve been able to find (Note: The link is in an essay on Duchamp and the “Fountain” on the Phaidon website [scroll down to the ninth paragraph]),

Allen Norton was an American poet and literary editor of the 1910s and 20s. He and his wife Louise Norton [emphasis mine] edited the little magazine Rogue, published from March 1915 to December 1916.

There is another Louise Norton, an artist who has a Wikipedia entry but that suggests this is an entirely different ‘Louise’.

Of the two and for what it’s worth, I find von Freytag-Loringhoven to be the more credible candidate. Nell Frizzell in her Nov. 7, 2014 opinion piece for the Guardian has absolutely no doubts on the matter (Note: Links have been removed),

Men may fill them, but it takes a woman to take the piss out of a urinal. Or so Julian Spalding, the former director of Glasgow Museums, and the academic Glyn Thompson have claimed. The argument, which has been swooshing around the cistern of contemporary art criticism since the 1980s, is that Duchamp’s famous artwork Fountain – a pissoir laid on its side – was actually the creation of the poet, artist and wearer of tin cans, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

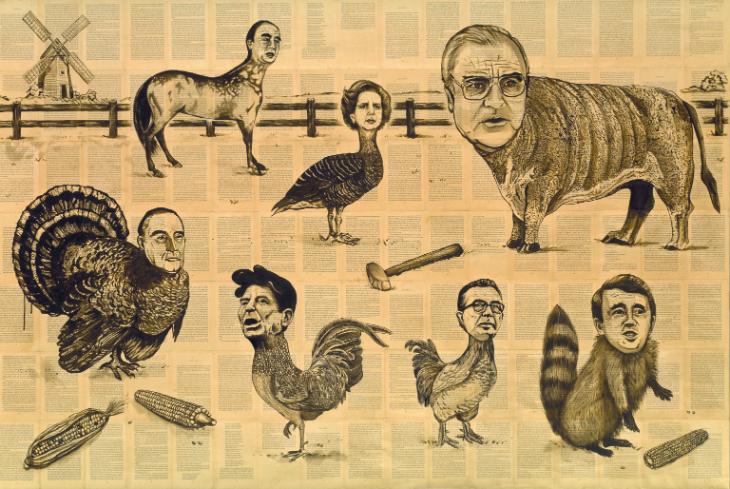

That Von Freytag-Loringhoven has been written out of the story is not only a great injustice, it is also a formidable loss to art history. This was a woman, after all, whose idea of getting gussied-up for a private view was to scatter her outfit liberally with flattened tin cans and stuffed parrots. A woman who danced on verandas in little more than a pair of stockings, some feathers and enough bangles to shake out the percussion track from Walk Like an Egyptian. A woman who draped her way through several open marriages, including one to Oscar Wilde’s translator Felix Paul Greve (who faked his own suicide to escape his creditors and flee with her to America)….

…

Mind you, there is a difference between theft and misattribution. While Valerie Solanas, the somewhat troubled feminist and writer of the Scum manifesto, openly accused Andy Warhol of stealing her script Up Your Ass and even attempted to murder him, other works exist in a more complicated, murky grey area. Matisse certainly directed the creation of his gouaches découpées – large collage works made by pasting torn-off pieces of gouache-painted paper – yet it is impossible to draw the line between where his creativity ends and that of his assistants intention begins. Similarly, while John Milton’s daughters ostensibly simply transcribed their father’s work, how can we say that in the act of writing they were not also editing, questioning, suggesting imagery and offering phrasing?

…

Art historians and academics have pointed out that in 1917 Duchamp wrote to his sister, recounting how “one of my female friends under a masculine pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture”. Duchamp revealed that this model of urinal wasn’t even in production at the factory where he claimed to have picked it up; and that this artwork bore a more than passing similarity to the Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven readymade sculpture called God, both in appearance and concept.

…

Here is “God,”

“God” By Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven and Morton Schamberg (1917)Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Blue pencil.svg wikidata:Q1565911 Source/Photographer: TgGFztK3lZWxdg at Google Cultural Institute, zoom level maximum

The “Fountain” graced this blog previously in a March 8, 2016 posting about an exhibition titled: “Mashup: The Birth of Modern Culture” at the Vancouver Art Gallery where I did not have an inkling as to this controversy. Given the zeitgeist surrounding women and their issues, it’s an interesting time to learn of it.

![[downloaded from http://www.artnews.com/top200/bob-rennie/]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/BobRennie.jpg)