It’s a bit of a stretch but I really appreciate how the nanoscale (specifically a fullerene) is being paired with the second largest planet (the largest is Jupiter) in our solar system. (See Nola Taylor Redd’s November 14, 2012 article on space.com for more about the planet Saturn.)

From a June 8, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily,

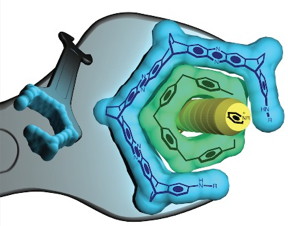

Saturn is the second largest planet in our solar system and has a characteristic ring. Japanese researchers have now synthesized a molecular “nano-Saturn.” As the scientists report in the journal Angewandte Chemie, it consists of a spherical C(60) fullerene as the planet and a flat macrocycle made of six anthracene units as the ring. The structure is confirmed by spectroscopic and X-ray analyses.

A June 8, 2018 Wiley Publications press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, fills in some details,

Nano-Saturn systems with a spherical molecule and a macrocyclic ring have been a fascinating structural motif for researchers. The ring must have a rigid, circular form, and must hold the molecular sphere firmly in its midst. Fullerenes are ideal candidates for the nano-sphere. They are made of carbon atoms linked into a network of rings that form a hollow sphere. The most famous fullerene, C60, consists of 60 carbon atoms arranged into 5- and 6-membered rings like the leather patches of a classic soccer ball. The electrons in their double bonds, knows as the π-electrons, are in a kind of “electron cloud”, able to freely move about and have binding interactions with other molecules, such as a macrocycle that also has a “cloud” of π-electrons. The attractive interactions between the electron clouds allow fullerenes to lodge in the cavities of such macrocycles.

A series of such complexes has previously been synthesized. Because of the positions of the electron clouds around the macrocycles, it was previously only possible to make rings that surround the fullerene like a belt or a tire. The ring around Saturn, however, is not like a “belt” or “tire”, it is a very flat disc. Researchers working at the Tokyo Institute of Technology and Okayama University of Science (Japan) wanted to properly imitate this at nanoscale.

Their success resulted from a different type of bonding between the “nano-planet” and its “nano-ring”. Instead of using the attraction between the π-electron clouds of the fullerene and macrocycle, the team working with Shinji Toyota used the weak attractive interactions between the π-electron cloud of the fullerene and non- π-electron of the carbon-hydrogen groups of the macrocycle.

To construct their “Saturn ring”, the researchers chose to use anthracene units, molecules made of three aromatic six-membered carbon rings linked along their edges. They linked six of these units into a macrocycle whose cavity was the perfect size and shape for a C60 fullerene. Eighteen hydrogen atoms of the macrocycle project into the middle of the cavity. In total, their interactions with the fullerene are enough to give the complex enough stability, as shown by computer simulations. By using X-ray analysis and NMR spectroscopy, the team was able to prove experimentally that they had produced Saturn-shaped complexes.

Here’s an illustration of the ‘nano-saturn’,

Courtesy: Wiley Publications

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Nano‐Saturn: Experimental Evidence of Complex Formation of an Anthracene Cyclic Ring with C60 by Yuta Yamamoto, Dr. Eiji Tsurumaki, Prof. Dr. Kan Wakamatsu, Prof. Dr. Shinji Toyota. Angewandte Chemie https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201804430 First published: 30 May 2018

This paper is behind a paywall.