Most of us don’t think too much about cartilage (soft, flexible connective tissue found in the body) unless it’s damaged in which case it’s importance becomes immediately apparent. There is no substitute for cartilage although scientists are working on that problem and it seems that one team may have made a significant breakthrough according to an April 27, 2014 news item on ScienceDaily,

In a significant step toward reducing the heavy toll of osteoarthritis around the world, scientists have created the first example of living human cartilage grown on a laboratory chip. The researchers ultimately aim to use their innovative 3-D printing approach to create replacement cartilage for patients with osteoarthritis or soldiers with battlefield injuries.

“Osteoarthritis has a severe impact on quality of life, and there is an urgent need to understand the origin of the disease and develop effective treatments” said Rocky Tuan, Ph.D., director of the Center for Cellular and Molecular Engineering at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, member of the American Association of Anatomists and the study’s senior investigator. “We hope that the methods we’re developing will really make a difference, both in the study of the disease and, ultimately, in treatments for people with cartilage degeneration or joint injuries.”

Osteoarthritis is marked by a gradual disintegration of cartilage, a flexible tissue that provides padding where bones come together in a joint. Causing severe pain and loss of mobility in joints such as knees and fingers, osteoarthritis is one of the leading causes of physical disability in the United States. It is estimated that up to 1 in 2 Americans will develop some form of the disease in their lifetime.

Although some treatments can help relieve arthritis symptoms, there is no cure. Many patients with severe arthritis ultimately require a joint replacement.

An April 27,2014 Experimental Biology (EB) 2014 news release provides more insight,

Tuan said artificial cartilage built using a patient’s own stem cells could offer enormous therapeutic potential. “Ideally we would like to be able to regenerate this tissue so people can avoid having to get a joint replacement, which is a pretty drastic procedure and is unfortunately something that some patients have to go through multiple times,” said Tuan.

In addition to offering relief for people with osteoarthritis, Tuan said replacement cartilage could also be a game-changer for people with debilitating joint injuries, such as soldiers with battlefield injuries. “We really want these technologies to help wounded warriors return to service or pursue a meaningful post-combat life,” said Tuan, who co-directs the Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine, a national consortium focused on developing regenerative therapies for injured soldiers. “We are on a mission.”

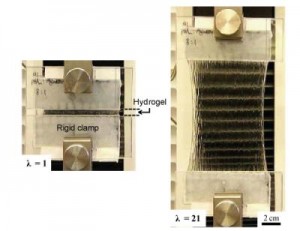

Creating artificial cartilage requires three main elements: stem cells, biological factors to make the cells grow into cartilage, and a scaffold to give the tissue its shape. Tuan’s 3-D printing approach achieves all three by extruding thin layers of stem cells embedded in a solution that retains its shape and provides growth factors. “We essentially speed up the development process by giving the cells everything they need, while creating a scaffold to give the tissue the exact shape and structure that we want,” said Tuan.

The ultimate vision is to give doctors a tool they can thread through a catheter to print new cartilage right where it’s needed in the patient’s body. Although other researchers have experimented with 3-D printing approaches for cartilage, Tuan’s method represents a significant step forward because it uses visible light, while others have required UV light, which can be harmful to living cells.

In another significant step, Tuan has successfully used the 3-D printing method to produce the first “tissue-on-a-chip” replica of the bone-cartilage interface. Housing 96 blocks of living human tissue 4 millimeters across by 8 millimeters deep, the chip could serve as a test-bed for researchers to learn about how osteoarthritis develops and develop new drugs. “With more testing, I think we’ll be able to use our platform to simulate osteoarthritis, which would be extremely useful since scientists really know very little about how the disease develops,” said Tuan.

As a next step, the team is working to combine their 3-D printing method with a nanofiber spinning technique they developed previously. They hope combining the two methods will provide a more robust scaffold and allow them to create artificial cartilage that even more closely resembles natural cartilage.

Rocky Tuan presented the research during the Experimental Biology 2014 meeting on Sunday, April 27 [2014].

I haven’t been able to find any papers published on this work but you can find Rocky Tuan’s faculty page (along with a list of publications) here and you may have more luck with the EB 2014 conference website than I did.