I was teaching an introductory course about nanotechnology back in 2014 and, at the end of a session, stated (more or less) that the full potential for artificial intelligence (software) wasn’t going to be perceived until the hardware (memistors) was part of the package. (It’s interesting to revisit that in light of the recent uproar around AI (covered in my May 25, 2023 posting, which offered a survey of the situation.)

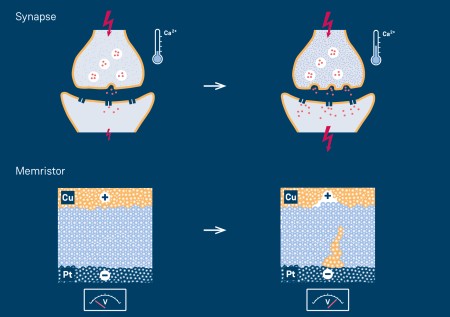

One of the major problems with artificial intelligence is its memory. The other is energy consumption. Both problems could be addressed by the integration of memristors into the hardware, giving rise to neuromorphic (brainlike) computing. (For those who don’t know, the human brain in addition to its capacity for memory is remarkably energy efficient.)

This is the first time I’ve seen research into memristors where software has been included. Disclaimer: There may be a lot more research of this type; I just haven’t seen it before. A March 24, 2023 news item on ScienceDaily announces research from Korea,

ChatGPT’s impact extends beyond the education sector and is causing significant changes in other areas. The AI language model is recognized for its ability to perform various tasks, including paper writing, translation, coding, and more, all through question-and-answer-based interactions. The AI system relies on deep learning, which requires extensive training to minimize errors, resulting in frequent data transfers between memory and processors. However, traditional digital computer systems’ von Neumann architecture separates the storage and computation of information, resulting in increased power consumption and significant delays in AI computations. Researchers have developed semiconductor technologies suitable for AI applications to address this challenge.

…

A March 24, 2023 Pohang University of Science & Technology (POSTECH) press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more detail,

A research team at POSTECH, led by Professor Yoonyoung Chung (Department of Electrical Engineering, Department of Semiconductor Engineering), Professor Seyoung Kim (Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Department of Semiconductor Engineering), and Ph.D. candidate Seongmin Park (Department of Electrical Engineering), has developed a high-performance AI semiconductor device [emphasis mine] using indium gallium zinc oxide (IGZO), an oxide semiconductor widely used in OLED [organic light-emitting diode] displays. The new device has proven to be excellent in terms of performance and power efficiency.

Efficient AI operations, such as those of ChatGPT, require computations to occur within the memory responsible for storing information. Unfortunately, previous AI semiconductor technologies were limited in meeting all the requirements, such as linear and symmetric programming and uniformity, to improve AI accuracy.

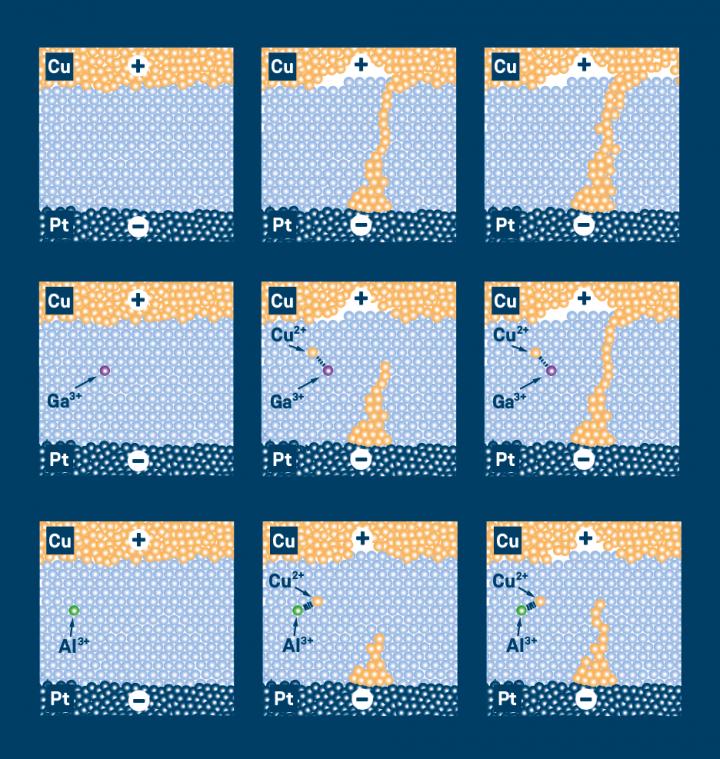

The research team sought IGZO as a key material for AI computations that could be mass-produced and provide uniformity, durability, and computing accuracy. This compound comprises four atoms in a fixed ratio of indium, gallium, zinc, and oxygen and has excellent electron mobility and leakage current properties, which have made it a backplane of the OLED display.

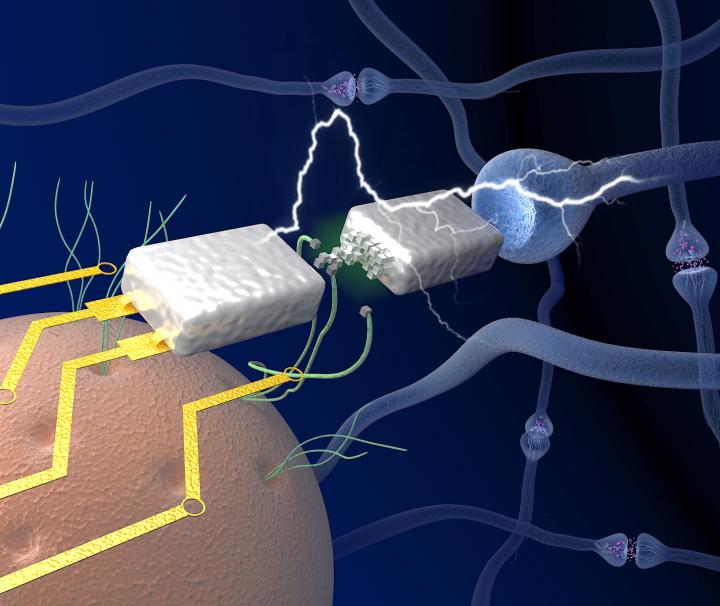

Using this material, the researchers developed a novel synapse device [emphasis mine] composed of two transistors interconnected through a storage node. The precise control of this node’s charging and discharging speed has enabled the AI semiconductor to meet the diverse performance metrics required for high-level performance. Furthermore, applying synaptic devices to a large-scale AI system requires the output current of synaptic devices to be minimized. The researchers confirmed the possibility of utilizing the ultra-thin film insulators inside the transistors to control the current, making them suitable for large-scale AI.

The researchers used the newly developed synaptic device to train and classify handwritten data, achieving a high accuracy of over 98%, [emphasis mine] which verifies its potential application in high-accuracy AI systems in the future.

Professor Chung explained, “The significance of my research team’s achievement is that we overcame the limitations of conventional AI semiconductor technologies that focused solely on material development. To do this, we utilized materials already in mass production. Furthermore, Linear and symmetrical programming characteristics were obtained through a new structure using two transistors as one synaptic device. Thus, our successful development and application of this new AI semiconductor technology show great potential to improve the efficiency and accuracy of AI.”

This study was published last week [March 2023] on the inside back cover of Advanced Electronic Materials [paper edition] and was supported by the Next-Generation Intelligent Semiconductor Technology Development Program through the National Research Foundation, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT [Information and Communication Technologies] of Korea.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Highly Linear and Symmetric Analog Neuromorphic Synapse Based on Metal Oxide Semiconductor Transistors with Self-Assembled Monolayer for High-Precision Neural Network Computatio by Seongmin Park, Suwon Seong, Gilsu Jeon, Wonjae Ji, Kyungmi Noh, Seyoung Kim, Yoonyoung Chun. Volume 9, Issue 3 March 2023 2200554 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/aelm.202200554 First published online: 29 December 2022

This paper is open access.

Also, there is another approach to using materials such as indium gallium zinc oxide (IGZO) for a memristor. That would be using biological cells as my June 6, 2023 posting, which features work on biological neural networks (BNNs), suggests in relation to creating robots that can perform brainlike computing.