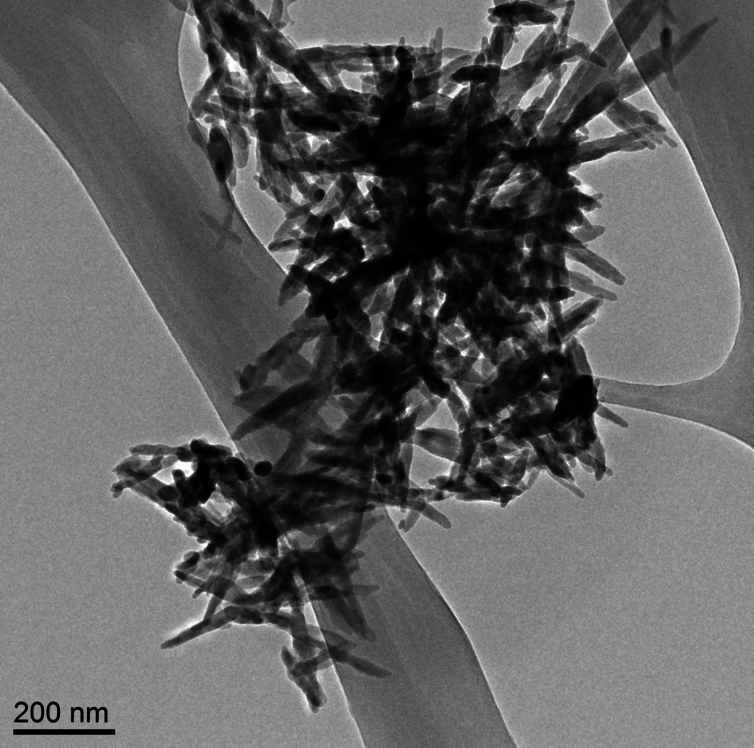

Needle-like particles of hydroxyapatite found in infant formula by ASU [Arizona State University] researchers. Westerhoff and Schoepf/ASU, CC BY-ND

There’s a lot of stuff you’d expect to find in baby formula: proteins, carbs, vitamins, essential minerals. But parents probably wouldn’t anticipate finding extremely small, needle-like particles. Yet this is exactly what a team of scientists here at Arizona State University [ASU] recently discovered.

The research, commissioned and published by Friends of the Earth (FoE) – an environmental advocacy group – analyzed six commonly available off-the-shelf baby formulas (liquid and powder) and found nanometer-scale needle-like particles in three of them. The particles were made of hydroxyapatite – a poorly soluble calcium-rich mineral. Manufacturers use it to regulate acidity in some foods, and it’s also available as a dietary supplement.

Andrew’s May 17, 2016 essay first appeared on The Conversation website,

Looking at these particles at super-high magnification, it’s hard not to feel a little anxious about feeding them to a baby. They appear sharp and dangerous – not the sort of thing that has any place around infants. …

… questions like “should infants be ingesting them?” make a lot of sense. However, as is so often the case, the answers are not quite so straightforward.

Andrew begins by explaining about calcium and hydroxyapatite (from The Conversation),

Calcium is an essential part of a growing infant’s diet, and is a legally required component in formula. But not necessarily in the form of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles.

Hydroxyapatite is a tough, durable mineral. It’s naturally made in our bodies as an essential part of bones and teeth – it’s what makes them so strong. So it’s tempting to assume the substance is safe to eat. But just because our bones and teeth are made of the mineral doesn’t automatically make it safe to ingest outright.

The issue here is what the hydroxyapatite in formula might do before it’s digested, dissolved and reconstituted inside babies’ bodies. The size and shape of the particles ingested has a lot to do with how they behave within a living system.

He then discusses size and shape, which are important at the nanoscale,

Size and shape can make a difference between safe and unsafe when it comes to particles in our food. Small particles aren’t necessarily bad. But they can potentially get to parts of our body that larger ones can’t reach. Think through the gut wall, into the bloodstream, and into organs and cells. Ingested nanoscale particles may be able to interfere with cells – even beneficial gut microbes – in ways that larger particles don’t.

These possibilities don’t necessarily make nanoparticles harmful. Our bodies are pretty well adapted to handling naturally occurring nanoscale particles – you probably ate some last time you had burnt toast (carbon nanoparticles), or poorly washed vegetables (clay nanoparticles from the soil). And of course, how much of a material we’re exposed to is at least as important as how potentially hazardous it is.

Yet there’s a lot we still don’t know about the safety of intentionally engineered nanoparticles in food. Toxicologists have started paying close attention to such particles, just in case their tiny size makes them more harmful than otherwise expected.

Currently, hydroxyapatite is considered safe at the macroscale by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, the agency has indicated that nanoscale versions of safe materials such as hydroxyapatite may not be safe food additives. From Andrew’s May 17, 2016 essay,

Hydroxyapatite is a tough, durable mineral. It’s naturally made in our bodies as an essential part of bones and teeth – it’s what makes them so strong. So it’s tempting to assume the substance is safe to eat. But just because our bones and teeth are made of the mineral doesn’t automatically make it safe to ingest outright.

The issue here is what the hydroxyapatite in formula might do before it’s digested, dissolved and reconstituted inside babies’ bodies. The size and shape of the particles ingested has a lot to do with how they behave within a living system. Size and shape can make a difference between safe and unsafe when it comes to particles in our food. Small particles aren’t necessarily bad. But they can potentially get to parts of our body that larger ones can’t reach. Think through the gut wall, into the bloodstream, and into organs and cells. Ingested nanoscale particles may be able to interfere with cells – even beneficial gut microbes – in ways that larger particles don’t.These possibilities don’t necessarily make nanoparticles harmful. Our bodies are pretty well adapted to handling naturally occurring nanoscale particles – you probably ate some last time you had burnt toast (carbon nanoparticles), or poorly washed vegetables (clay nanoparticles from the soil). And of course, how much of a material we’re exposed to is at least as important as how potentially hazardous it is.Yet there’s a lot we still don’t know about the safety of intentionally engineered nanoparticles in food. Toxicologists have started paying close attention to such particles, just in case their tiny size makes them more harmful than otherwise expected.

…

Putting particle size to one side for a moment, hydroxyapatite is classified by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as “Generally Regarded As Safe.” That means it considers the material safe for use in food products – at least in a non-nano form. However, the agency has raised concerns that nanoscale versions of food ingredients may not be as safe as their larger counterparts.Some manufacturers may be interested in the potential benefits of “nanosizing” – such as increasing the uptake of vitamins and minerals, or altering the physical, textural and sensory properties of foods. But because decreasing particle size may also affect product safety, the FDA indicates that intentionally nanosizing already regulated food ingredients could require regulatory reevaluation.In other words, even though non-nanoscale hydroxyapatite is “Generally Regarded As Safe,” according to the FDA, the safety of any nanoscale form of the substance would need to be reevaluated before being added to food products.Despite this size-safety relationship, the FDA confirmed to me that the agency is unaware of any food substance intentionally engineered at the nanoscale that has enough generally available safety data to determine it should be “Generally Regarded As Safe.”Casting further uncertainty on the use of nanoscale hydroxyapatite in food, a 2015 report from the European Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety (SCCS) suggests there may be some cause for concern when it comes to this particular nanomaterial.Prompted by the use of nanoscale hydroxyapatite in dental products to strengthen teeth (which they consider “cosmetic products”), the SCCS reviewed published research on the material’s potential to cause harm. Their conclusion?

The available information indicates that nano-hydroxyapatite in needle-shaped form is of concern in relation to potential toxicity. Therefore, needle-shaped nano-hydroxyapatite should not be used in cosmetic products.

This recommendation was based on a handful of studies, none of which involved exposing people to the substance. Researchers injected hydroxyapatite needles directly into the bloodstream of rats. Others exposed cells outside the body to the material and observed the effects. In each case, there were tantalizing hints that the small particles interfered in some way with normal biological functions. But the results were insufficient to indicate whether the effects were meaningful in people.

As Andrew also notes in his essay, none of the studies examined by the SCCS OEuropean Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety) looked at what happens to nano-hydroxyapatite once it enters your gut and that is what the researchers at Arizona State University were considering (from the May 17, 2016 essay),

The good news is that, according to preliminary studies from ASU researchers, hydroxyapatite needles don’t last long in the digestive system.

This research is still being reviewed for publication. But early indications are that as soon as the needle-like nanoparticles hit the highly acidic fluid in the stomach, they begin to dissolve. So fast in fact, that by the time they leave the stomach – an exceedingly hostile environment – they are no longer the nanoparticles they started out as.

These findings make sense since we know hydroxyapatite dissolves in acids, and small particles typically dissolve faster than larger ones. So maybe nanoscale hydroxyapatite needles in food are safer than they sound.

This doesn’t mean that the nano-needles are completely off the hook, as some of them may get past the stomach intact and reach more vulnerable parts of the gut. But the findings do suggest these ultra-small needle-like particles could be an effective source of dietary calcium – possibly more so than larger or less needle-like particles that may not dissolve as quickly.

Intriguingly, recent research has indicated that calcium phosphate nanoparticles form naturally in our stomachs and go on to be an important part of our immune system. It’s possible that rapidly dissolving hydroxyapatite nano-needles are actually a boon, providing raw material for these natural and essential nanoparticles.

While it’s comforting to know that preliminary research suggests that the hydroxyapatite nanoparticles are likely safe for use in food products, Andrew points out that more needs to be done to insure safety (from the May 17, 2016 essay),

And yet, even if these needle-like hydroxyapatite nanoparticles in infant formula are ultimately a good thing, the FoE report raises a number of unresolved questions. Did the manufacturers knowingly add the nanoparticles to their products? How are they and the FDA ensuring the products’ safety? Do consumers have a right to know when they’re feeding their babies nanoparticles?

Whether the manufacturers knowingly added these particles to their formula is not clear. At this point, it’s not even clear why they might have been added, as hydroxyapatite does not appear to be a substantial source of calcium in most formula. …

…

And regardless of the benefits and risks of nanoparticles in infant formula, parents have a right to know what’s in the products they’re feeding their children. In Europe, food ingredients must be legally labeled if they are nanoscale. In the U.S., there is no such requirement, leaving American parents to feel somewhat left in the dark by producers, the FDA and policy makers.

…

As far as I’m aware, the Canadian situation is much the same as the US. If the material is considered safe at the macroscale, there is no requirement to indicate that a nanoscale version of the material is in the product.

I encourage you to read Andrew’s essay in its entirety. As for the FoE report (Nanoparticles in baby formula: Tiny new ingredients are a big concern), that is here.