Let’s take a look at the bone patch developed at the University Iowa,

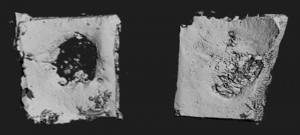

Researchers at the University of Iowa have created a bio patch to regenerate missing or damaged bone. The patch has been shown to nearly fully regrow missing skull, seen in the image above. Image courtesy of Satheesh Elangovan. & University of Iowa

A Nov. 7, 2013 news item on Nanowerk provides information explaining the bone bio-patch,

Researchers at the University of Iowa have created a bio patch to regenerate missing or damaged bone by putting DNA into a nano-sized particle that delivers bone-producing instructions directly into cells.

The bone-regeneration kit relies on a collagen platform seeded with particles containing the genes needed for producing bone. In experiments, the gene-encoding bio patch successfully regrew bone fully enough to cover skull wounds in test animals. It also stimulated new growth in human bone marrow stromal cells in lab experiments.

The study is novel in that the researchers directly delivered bone-producing instructions (using piece of DNA that encodes for a platelet-derived growth factor called PDGF-B) to existing bone cells in vivo, allowing those cells to produce the proteins that led to more bone production. Previous attempts had relied on repeated applications from the outside, which is costly, intensive, and harder to replicate consistently.

The Nov. 6, 2013 University of Iowa news piece, which originated the news item and was written by Richard C. Lewis, provides some insight from the researchers (Note: Links have been removed),

“We delivered the DNA to the cells, so that the cells produce the protein and that’s how the protein is generated to enhance bone regeneration,” explains Aliasger Salem, professor in the College of Pharmacy and a co-corresponding author on the paper, published in the journal Biomaterials. ”If you deliver just the protein, you have keep delivering it with continuous injections to maintain the dose. With our method, you get local, sustained expression over a prolonged period of time without having to give continued doses of protein.”

The researchers believe the patch has several potential uses in dentistry. For instance, it could be used to rebuild bone in the gum area that serves as the concrete-like foundation for dental implants. That prospect would be a “life-changing experience” for patients who need implants and don’t have enough bone in the surrounding area, says Satheesh Elangovan, assistant professor in the UI’s College of Dentistry and a joint first author, as well as co-corresponding author, on the paper. It also can be used to repair birth defects where there’s missing bone around the head or face.

“We can make a scaffold in the actual shape and size of the defect site, and you’d get complete regeneration to match the shape of what should have been there,” Elangovan says.

The news article goes on to provide details about how the bio-patch was created,

The team started with a collagen scaffold. The researchers then loaded the bio patch with synthetically created plasmids, each of which is outfitted with the genetic instructions for producing bone. They then inserted the scaffold on to a 5-millimeter by 2-millimeter missing area of skull in test animals. Four weeks later, the team compared the bio patch’s effectiveness to inserting a scaffold with no plasmids or taking no action at all.

The plasmid-seeded bio patch grew 44-times more bone and soft tissue in the affected area than with the scaffold alone, and was 14-fold higher than the affected area with no manipulation. Aerial and cross-sectional scans showed the plasmid-encoded scaffolds had spurred enough new bone growth to nearly close the wound area, the researchers report.

The plasmid does its work by entering bone cells already in the body – usually those located right around the damaged area that wander over to the scaffold. The team used a polymer to shrink the particle’s size (like creating a zip file, for example) and to give the plasmid the positive electrical charge that would make it easier for the resident bone cells to take them in.

“The delivery mechanism is the scaffold loaded with the plasmid,” Salem says. “When cells migrate into the scaffold, they meet with the plasmid, they take up the plasmid, and they get the encoding to start producing PDGF-B, which enhances bone regeneration.”

The researchers also point out that their delivery system is nonviral. That means the plasmid is less likely to cause an undesired immune response and is easier to produce in mass quantities, which lowers the cost.

“The most exciting part to me is that we were able to develop an efficacious, nonviral-based gene-delivery system for treating bone loss,” says Sheetal D’mello, a graduate student in pharmacy and a joint first author on the paper.

Elangovan and Salem next hope to create a bio platform that promotes new blood vessel growth– needed for extended and sustained bone growth.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the published paper,

The enhancement of bone regeneration by gene activated matrix encoding for platelet derived growth factor by Satheesh Elangovan, Sheetal R. D’Mello, Liu Hong, Ryan D. Ross, Chantal Allamargot, Deborah V. Dawson, Clark M. Stanford, Georgia K. Johnson, D. Rick Sumnerd,& Aliasger K. Salem. Biomaterials Volume 35, Issue 2, January 2014, Pages 737–747 DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.021

This paper is behind a paywall.