There’s more than one way to approach the introduction of emerging technologies and sciences to ‘the public’. Calestous Juma in his 2016 book, ”Innovation and Its Enemies; Why People Resist New Technologies” takes a direct approach, as can be seen from the title while Melanie Keene’s 2015 book, “Science in Wonderland; The Scientific Fairy Tales of Victorian Britain” presents a more fantastical one. The fish in the headline tie together, thematically and tenuously, both books with a real life situation.

Innovation and Its Enemies

Calestous Juma, the author of “Innovation and Its Enemies” has impressive credentials,

- Professor of the Practice of International Development,

- Director of the Science, Technology, and Globalization Project at Harvard Kennedy School’s Better Science and International Affairs,

- Founding Director of the African Centre for Technology Studies in Nairobi (Kenya),

- Fellow of the Royal Society of London, and

- Foreign Associate of the US National Academy of Sciences.

Even better, Juma is an excellent storyteller perhaps too much so for a book which presents a series of science and technology adoption case histories. (Given the range of historical time periods, geography, and the innovations themselves, he always has to stop short.) The breadth is breathtaking and Juma manages with aplomb. For example, the innovations covered include: coffee, electricity, mechanical refrigeration, margarine, recorded sound, farm mechanization, and the printing press. He also covers two recently emerging technologies/innovations: transgenic crops and AquAdvantage salmon (more about the salmon later).

Juma provides an analysis of the various ways in which the public and institutions panic over innovation and goes on to offer solutions. He also injects a subtle note of humour from time to time. Here’s how Juma describes various countries’ response to risks and benefits,

In the United States products are safe until proven risky.

In France products are risky until proven safe.

In the United Kingdom products are risky even when proven safe.

In India products are safe when proven risky.

In Canada products are neither safe nor risky.

In Japan products are either safe or risky.

In Brazil products are both safe and risky.

In sub-Saharan Africa products are risky even if they do not exist. (pp. 4-5)

To Calestous Juma, thank you for mentioning Canada and for so aptly describing the quintessentially Canadian approach to not just products and innovation but to life itself, ‘we just don’t know; it could be this or it could be that or it could be something entirely different; we just don’t know and probably will never know.’.

One of the aspects that I most appreciated in this book was the broadening of the geographical perspective on innovation and emerging technologies to include the Middle East, China, and other regions/countries. As I’ve noted in past postings, much of the discussion here in Canada is Eurocentric and/or UScentric. For example, the Council of Canadian Academies which conducts assessments of various science questions at the request of Canadian and regional governments routinely fills the ‘international’ slot(s) for their expert panels with academics from Europe (mostly Great Britain) and/or the US (or sometimes from Australia and/or New Zealand).

A good example of Juma’s expanded perspective on emerging technology is offered in Art Carden’s July 7, 2017 book review for Forbes.com (Note: A link has been removed),

In the chapter on coffee, Juma discusses how Middle Eastern and European societies resisted the beverage and, in particular, worked to shut down coffeehouses. Islamic jurists debated whether the kick from coffee is the same as intoxication and therefore something to be prohibited. Appealing to “the principle of original permissibility — al-ibaha, al-asliya — under which products were considered acceptable until expressly outlawed,” the fifteenth-century jurist Muhamad al-Dhabani issued several fatwas in support of keeping coffee legal.

This wasn’t the last word on coffee, which was banned and permitted and banned and permitted and banned and permitted in various places over time. Some rulers were skeptical of coffee because it was brewed and consumed in public coffeehouses — places where people could indulge in vices like gambling and tobacco use or perhaps exchange unorthodox ideas that were a threat to their power. It seems absurd in retrospect, but political control of all things coffee is no laughing matter.

The bans extended to Europe, where coffee threatened beverages like tea, wine, and beer. Predictably, and all in the name of public safety (of course!), European governments with the counsel of experts like brewers, vintners, and the British East India Tea Company regulated coffee importation and consumption. The list of affected interest groups is long, as is the list of meddlesome governments. Charles II of England would issue A Proclamation for the Suppression of Coffee Houses in 1675. Sweden prohibited coffee imports on five separate occasions between 1756 and 1817. In the late seventeenth century, France required that all coffee be imported through Marseilles so that it could be more easily monopolized and taxed.

Carden who teaches economics at Stanford University (California, US) focuses on issues of individual liberty and the rule of law with regards to innovation. I can appreciate the need to focus tightly when you have a limited word count but Carden could have a spared a few words to do more justice to Juma’s comprehensive and focused work.

At the risk of being accused of the fault I’ve attributed to Carden, I must mention the printing press chapter. While it was good to see a history of the printing press and attendant social upheavals noting its impact and discovery in regions other than Europe; it was shocking to someone educated in Canada to find Marshall McLuhan entirely ignored. Even now, I believe it’s virtually impossible to discuss the printing press as a technology, in Canada anyway, without mentioning our ‘communications god’ Marshall McLuhan and his 1962 book, The Gutenberg Galaxy.

Getting back to Juma’s book, his breadth and depth of knowledge, history, and geography is packaged in a relatively succinct 316 pp. As a writer, I admire his ability to distill the salient points and to devote chapters on two emerging technologies. It’s notoriously difficult to write about a currently emerging technology and Juma even managed to include a reference published only months (in early 2016) before “Innovation and its enemires” was published in July 2016.

Irrespective of Marshall McLuhan, I feel there are a few flaws. The book is intended for policy makers and industry (lobbyists, anyone?), he reaffirms (in academia, industry, government) a tendency toward a top-down approach to eliminating resistance. From Juma’s perspective, there needs to be better science education because no one who is properly informed should have any objections to an emerging/new technology. Juma never considers the possibility that resistance to a new technology might be a reasonable response. As well, while there was some mention of corporate resistance to new technologies which might threaten profits and revenue, Juma didn’t spare any comments about how corporate sovereignty and/or intellectual property issues are used to stifle innovation and quite successfully, by the way.

My concerns aside, testimony to the book’s worth is Carden’s review almost a year after publication. As well, Sir Peter Gluckman, Chief Science Advisor to the federal government of New Zealand, mentions Juma’s book in his January 16, 2017 talk, Science Advice in a Troubled World, for the Canadian Science Policy Centre.

Science in Wonderland

Melanie Keene’s 2015 book, “Science in Wonderland; The scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain” provides an overview of the fashion for writing and reading scientific and mathematical fairy tales and, inadvertently, provides an overview of a public education programme,

A fairy queen (Victoria) sat on the throne of Victoria’s Britain, and she presided over a fairy tale age. The nineteenth century witnessed an unprecedented interest in fairies and in their tales, as they were used as an enchanted mirror in which to reflection question, and distort contemporary society.30 … Fairies could be found disporting themselves thought the century on stage and page, in picture and print, from local haunts to global transports. There were myriad ways in which authors, painters, illustrators, advertisers, pantomime performers, singers, and more, capture this contemporary enthusiasm and engaged with fairyland and folklore; books, exhibitions, and images for children were one of the most significant. (p. 13)

…

… Anthropologists even made fairies the subject of scientific analysis, as ‘fairyology’ determined whether fairies should be part of natural history or part of supernatural lore; just on aspect of the revival of interest in folklore. Was there a tribe of fairy creatures somewhere out thee waiting to be discovered, across the globe of in the fossil record? Were fairies some kind of folks memory of any extinct race? (p. 14)

…

Scientific engagements with fairyland was widespread, and not just as an attractive means of packaging new facts for Victorian children.42 … The fairy tales of science had an important role to play in conceiving of new scientific disciplines; in celebrating new discoveries; in criticizing lofty ambitions; in inculcating habits of mind and body; in inspiring wonder; in positing future directions; and in the consideration of what the sciences were, and should be. A close reading of these tales provides a more sophisticated understanding of the content and status of the Victorian sciences; they give insights into what these new scientific disciplines were trying to do; how they were trying to cement a certain place in the world; and how they hoped to recruit and train new participants. (p. 18)

Segue: Should you be inclined to believe that society has moved on from fairies; it is possible to become a certified fairyologist (check out the fairyologist.com website).

“Science in Wonderland,” the title being a reference to Lewis Carroll’s Alice, was marketed quite differently than “innovation and its enemies”. There is no description of the author, as is the protocol in academic tomes, so here’s more from her webpage on the University of Cambridge (Homerton College) website,

Role:

Fellow, Graduate Tutor, Director of Studies for History and Philosophy of Science

Getting back to Keene’s book, she makes the point that the fairy tales were based on science and integrated scientific terminology in imaginative ways although some books with more success than other others. Topics ranged from paleontology, botany, and astronomy to microscopy and more.

This book provides a contrast to Juma’s direct focus on policy makers with its overview of the fairy narratives. Keene is primarily interested in children but her book casts a wider net “… they give insights into what these new scientific disciplines were trying to do; how they were trying to cement a certain place in the world; and how they hoped to recruit and train new participants.”

In a sense both authors are describing how technologies are introduced and integrated into society. Keene provides a view that must seem almost halcyon for many contemporary innovation enthusiasts. As her topic area is children’s literature any resistance she notes is primarily literary invoking a debate about whether or not science was killing imagination and whimsy.

It would probably help if you’d taken a course in children’s literature of the 19th century before reading Keene’s book is written . Even if you haven’t taken a course, it’s still quite accessible, although I was left wondering about ‘Alice in Wonderland’ and its relationship to mathematics (see Melanie Bayley’s December 16, 2009 story for the New Scientist for a detailed rundown).

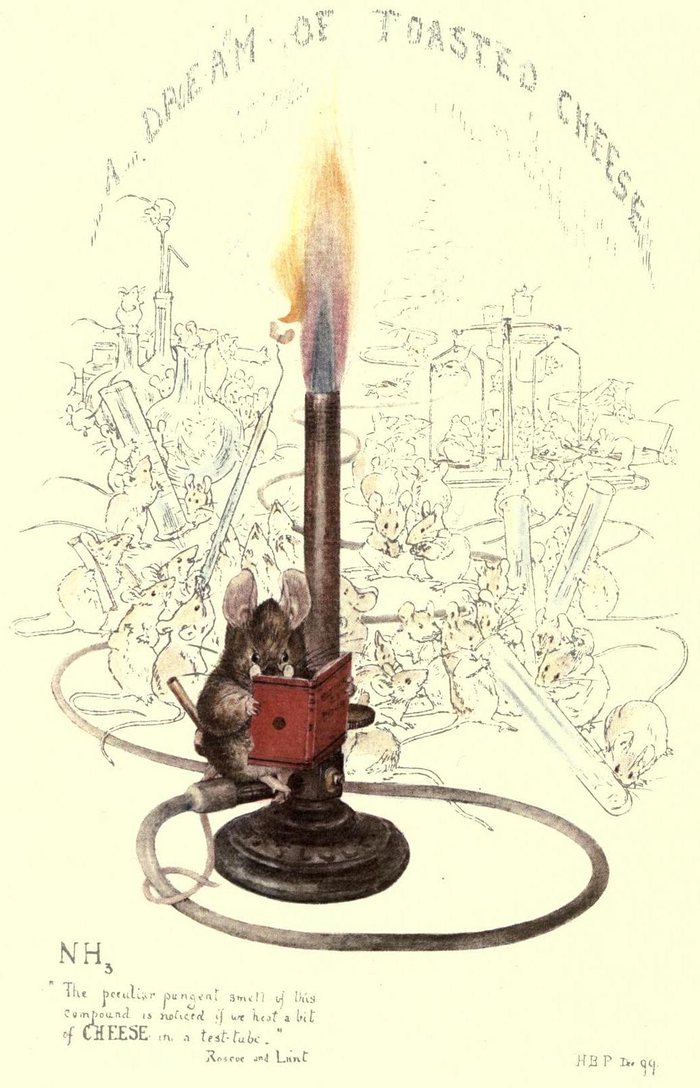

As an added bonus, fairy tale illustrations are included throughout the book along with a section of higher quality reproductions.

One of the unexpected delights of Keene’s book was the section on L. Frank Baum and his electricity fairy tale, “The Master Key.” She stretches to include “The Wizard of Oz,” which doesn’t really fit but I can’t see how she could avoid mentioning Baum’s most famous creation. There’s also a surprising (to me) focus on water, which when it’s paired with the interest in microscopy makes sense. Keene isn’t the only one who has to stretch to make things fit into her narrative and so from water I move onto fish bringing me back to one of Juma’s emerging technologies

Part 2: Fish and final comments