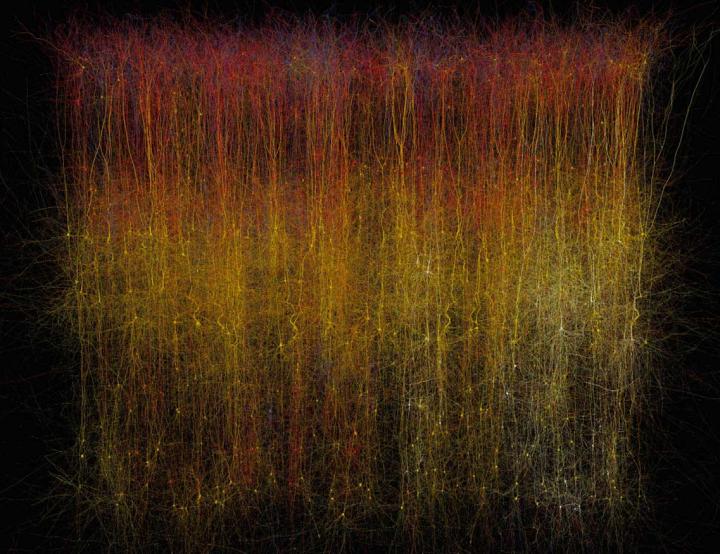

Here’s more *about this virtual brain slice* from an Oct. 8, 2015 Cell (magazine) news release on EurekAlert,

If you want to learn how something works, one strategy is to take it apart and put it back together again [also known as reverse engineering]. For 10 years, a global initiative called the Blue Brain Project–hosted at the Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL)–has been attempting to do this digitally with a section of juvenile rat brain. The project presents a first draft of this reconstruction, which contains over 31,000 neurons, 55 layers of cells, and 207 different neuron subtypes, on October 8 [2015] in Cell.

Heroic efforts are currently being made to define all the different types of neurons in the brain, to measure their electrical firing properties, and to map out the circuits that connect them to one another. These painstaking efforts are giving us a glimpse into the building blocks and logic of brain wiring. However, getting a full, high-resolution picture of all the features and activity of the neurons within a brain region and the circuit-level behaviors of these neurons is a major challenge.

Henry Markram and colleagues have taken an engineering approach to this question by digitally reconstructing a slice of the neocortex, an area of the brain that has benefitted from extensive characterization. Using this wealth of data, they built a virtual brain slice representing the different neuron types present in this region and the key features controlling their firing and, most notably, modeling their connectivity, including nearly 40 million synapses and 2,000 connections between each brain cell type.

“The reconstruction required an enormous number of experiments,” says Markram, of the EPFL. “It paves the way for predicting the location, numbers, and even the amount of ion currents flowing through all 40 million synapses.”

Once the reconstruction was complete, the investigators used powerful supercomputers to simulate the behavior of neurons under different conditions. Remarkably, the researchers found that, by slightly adjusting just one parameter, the level of calcium ions, they could produce broader patterns of circuit-level activity that could not be predicted based on features of the individual neurons. For instance, slow synchronous waves of neuronal activity, which have been observed in the brain during sleep, were triggered in their simulations, suggesting that neural circuits may be able to switch into different “states” that could underlie important behaviors.

“An analogy would be a computer processor that can reconfigure to focus on certain tasks,” Markram says. “The experiments suggest the existence of a spectrum of states, so this raises new types of questions, such as ‘what if you’re stuck in the wrong state?'” For instance, Markram suggests that the findings may open up new avenues for explaining how initiating the fight-or-flight response through the adrenocorticotropic hormone yields tunnel vision and aggression.

The Blue Brain Project researchers plan to continue exploring the state-dependent computational theory while improving the model they’ve built. All of the results to date are now freely available to the scientific community at https:/

/ bbp. epfl. ch/ nmc-portal.

An Oct. 8, 2015 Hebrew University of Jerusalem press release on the Canadian Friends of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem website provides more detail,

Published by the renowned journal Cell, the paper is the result of a massive effort by 82 scientists and engineers at EPFL and at institutions in Israel, Spain, Hungary, USA, China, Sweden, and the UK. It represents the culmination of 20 years of biological experimentation that generated the core dataset, and 10 years of computational science work that developed the algorithms and built the software ecosystem required to digitally reconstruct and simulate the tissue.

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Prof. Idan Segev, a senior author of the research paper, said: “With the Blue Brain Project, we are creating a digital reconstruction of the brain and using supercomputer simulations of its electrical behavior to reveal a variety of brain states. This allows us to examine brain phenomena within a purely digital environment and conduct experiments previously only possible using biological tissue. The insights we gather from these experiments will help us to understand normal and abnormal brain states, and in the future may have the potential to help us develop new avenues for treating brain disorders.”

Segev, a member of the Hebrew University’s Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Brain Sciences and director of the university’s Department of Neurobiology, sees the paper as building on the pioneering work of the Spanish anatomist Ramon y Cajal from more than 100 years ago: “Ramon y Cajal began drawing every type of neuron in the brain by hand. He even drew in arrows to describe how he thought the information was flowing from one neuron to the next. Today, we are doing what Cajal would be doing with the tools of the day: building a digital representation of the neurons and synapses, and simulating the flow of information between neurons on supercomputers. Furthermore, the digitization of the tissue is open to the community and allows the data and the models to be preserved and reused for future generations.”

While a long way from digitizing the whole brain, the study demonstrates that it is feasible to digitally reconstruct and simulate brain tissue, and most importantly, to reveal novel insights into the brain’s functioning. Simulating the emergent electrical behavior of this virtual tissue on supercomputers reproduced a range of previous observations made in experiments on the brain, validating its biological accuracy and providing new insights into the functioning of the neocortex. This is a first step and a significant contribution to Europe’s Human Brain Project, which Henry Markram founded, and where EPFL is the coordinating partner.

Cell has made a video abstract available (it can be found with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem press release)

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Reconstruction and Simulation of Neocortical Microcircuitry by Henry Markram, Eilif Muller, Srikanth Ramaswamy, Michael W. Reimann, Marwan Abdellah, Carlos Aguado Sanchez, Anastasia Ailamaki, Lidia Alonso-Nanclares, Nicolas Antille, Selim Arsever, Guy Antoine Atenekeng Kahou, Thomas K. Berger, Ahmet Bilgili, Nenad Buncic, Athanassia Chalimourda, Giuseppe Chindemi, Jean-Denis Courcol, Fabien Delalondre, Vincent Delattre, Shaul Druckmann, Raphael Dumusc, James Dynes, Stefan Eilemann, Eyal Gal, Michael Emiel Gevaert, Jean-Pierre Ghobril, Albert Gidon, Joe W. Graham, Anirudh Gupta, Valentin Haenel, Etay Hay, Thomas Heinis, Juan B. Hernando, Michael Hines, Lida Kanari, Daniel Keller, John Kenyon, Georges Khazen, Yihwa Kim, James G. King, Zoltan Kisvarday, Pramod Kumbhar, Sébastien Lasserre, Jean-Vincent Le Bé, Bruno R.C. Magalhães, Angel Merchán-Pérez, Julie Meystre, Benjamin Roy Morrice, Jeffrey Muller, Alberto Muñoz-Céspedes, Shruti Muralidhar, Keerthan Muthurasa, Daniel Nachbaur, Taylor H. Newton, Max Nolte, Aleksandr Ovcharenko, Juan Palacios, Luis Pastor, Rodrigo Perin, Rajnish Ranjan, Imad Riachi, José-Rodrigo Rodríguez, Juan Luis Riquelme, Christian Rössert, Konstantinos Sfyrakis, Ying Shi, Julian C. Shillcock, Gilad Silberberg, Ricardo Silva, Farhan Tauheed, Martin Telefont, Maria Toledo-Rodriguez, Thomas Tränkler, Werner Van Geit, Jafet Villafranca Díaz, Richard Walker, Yun Wang, Stefano M. Zaninetta, Javier DeFelipe, Sean L. Hill, Idan Segev, Felix Schürmann. Cell, Volume 163, Issue 2, p456–492, 8 October 2015 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.029

This paper appears to be open access.

My most substantive description of the Blue Brain Project , previous to this, was in a Jan. 29, 2013 posting featuring the European Union’s (EU) Human Brain project and involvement from countries that are not members.

* I edited a redundant lede (That’s a virtual slice of a rat brain.), moved the second sentence to the lede while adding this: *about this virtual brain slice* on Oct. 16, 2015 at 0955 hours PST.