I gather buckybombs have something to do with cancer treatments. From a March 18, 2015 news item on ScienceDaily,

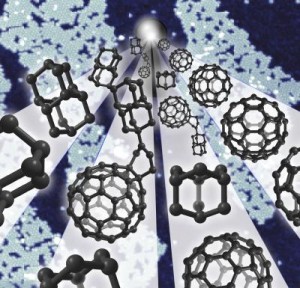

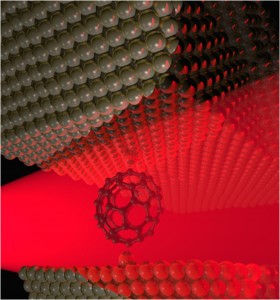

In 1996, a trio of scientists won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry for their discovery of Buckminsterfullerene — soccer-ball-shaped spheres of 60 joined carbon atoms that exhibit special physical properties.

Now, 20 years later, scientists have figured out how to turn them into Buckybombs.

These nanoscale explosives show potential for use in fighting cancer, with the hope that they could one day target and eliminate cancer at the cellular level — triggering tiny explosions that kill cancer cells with minimal impact on surrounding tissue.

“Future applications would probably use other types of carbon structures — such as carbon nanotubes, but we started with Bucky-balls because they’re very stable, and a lot is known about them,” said Oleg V. Prezhdo, professor of chemistry at the USC [University of Southern California] Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences and corresponding author of a paper on the new explosives that was published in The Journal of Physical Chemistry on February 24 [2015].

A March 19, 2015 USC news release by Robert Perkins, which despite its publication date originated the news item, describes current cancer treatments with carbon nanotubes and this new technique with fullerenes,

Carbon nanotubes, close relatives of Bucky-balls, are used already to treat cancer. They can be accumulated in cancer cells and heated up by a laser, which penetrates through surrounding tissues without affecting them and directly targets carbon nanotubes. Modifying carbon nanotubes the same way as the Buckybombs will make the cancer treatment more efficient — reducing the amount of treatment needed, Prezhdo said.

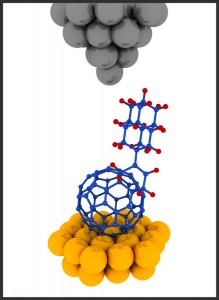

To build the miniature explosives, Prezhdo and his colleagues attached 12 nitrous oxide molecules to a single Bucky-ball and then heated it. Within picoseconds, the Bucky-ball disintegrated — increasing temperature by thousands of degrees in a controlled explosion.

The source of the explosion’s power is the breaking of powerful carbon bonds, which snap apart to bond with oxygen from the nitrous oxide, resulting in the creation of carbon dioxide, Prezhdo said.

I’m glad this technique would make treatment more effective but I do pause at the thought of having exploding buckyballs in my body or, for that matter, anyone else’s.

The research was highlighted earlier this month in a March 5, 2015 article by Lisa Zynga for phys.org,

The buckybomb combines the unique properties of two classes of materials: carbon structures and energetic nanomaterials. Carbon materials such as C60 can be chemically modified fairly easily to change their properties. Meanwhile, NO2 groups are known to contribute to detonation and combustion processes because they are a major source of oxygen. So, the scientists wondered what would happen if NO2 groups were attached to C60 molecules: would the whole thing explode? And how?

The simulations answered these questions by revealing the explosion in step-by-step detail. Starting with an intact buckybomb (technically called dodecanitrofullerene, or C60(NO2)12), the researchers raised the simulated temperature to 1000 K (700 °C). Within a picosecond (10-12 second), the NO2 groups begin to isomerize, rearranging their atoms and forming new groups with some of the carbon atoms from the C60. As a few more picoseconds pass, the C60 structure loses some of its electrons, which interferes with the bonds that hold it together, and, in a flash, the large molecule disintegrates into many tiny pieces of diatomic carbon (C2). What’s left is a mixture of gases including CO2, NO2, and N2, as well as C2.

I encourage you to read Zynga’s article in whole as she provides more scientific detail and she notes that this discovery could have applications for the military and for industry.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the researchers’ paper,

Buckybomb: Reactive Molecular Dynamics Simulation by Vitaly V. Chaban, Eudes Eterno Fileti, and Oleg V. Prezhdo. J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2015, 6 (5), pp 913–917 DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00120 Publication Date (Web): February 24, 2015

Copyright © 2015 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.