There is a fascinating set of stories about bioart designed to whet your appetite for more (*) in a Nov. 23, 2015 Cell Press news release on EurekAlert (Note: A link has been removed),

Joe Davis is an artist who works not only with paints or pastels, but also with genes and bacteria. In 1986, he collaborated with geneticist Dan Boyd to encode a symbol for life and femininity into an E. coli bacterium. The piece, called Microvenus, was the first artwork to use the tools and techniques of molecular biology. Since then, bioart has become one of several contemporary art forms (including reclamation art and nanoart) that apply scientific methods and technology to explore living systems as artistic subjects. A review of the field, published November 23, can be found in Trends in Biotechnology.

Bioart ranges from bacterial manipulation to glowing rabbits, cellular sculptures, and–in the case of Australian-British artist Nina Sellars–documentation of an ear prosthetic that was implanted onto fellow artist Stelarc’s arm. In the pursuit of creating art, practitioners have generated tools and techniques that have aided researchers, while sometimes crossing into controversy, such as by releasing invasive species into the environment, blurring the lines between art and modern biology, raising philosophical, societal, and environmental issues that challenge scientific thinking.

“Most people don’t know that bioart exists, but it can enable scientists to produce new ideas and give us opportunities to look differently at problems,” says author Ali K. Yetisen, who works at Harvard Medical School and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Massachusetts General Hospital. “At the same time there’s been a lot of ethical and safety concerns happening around bioart and artists who wanted to get involved in the past have made mistakes.”

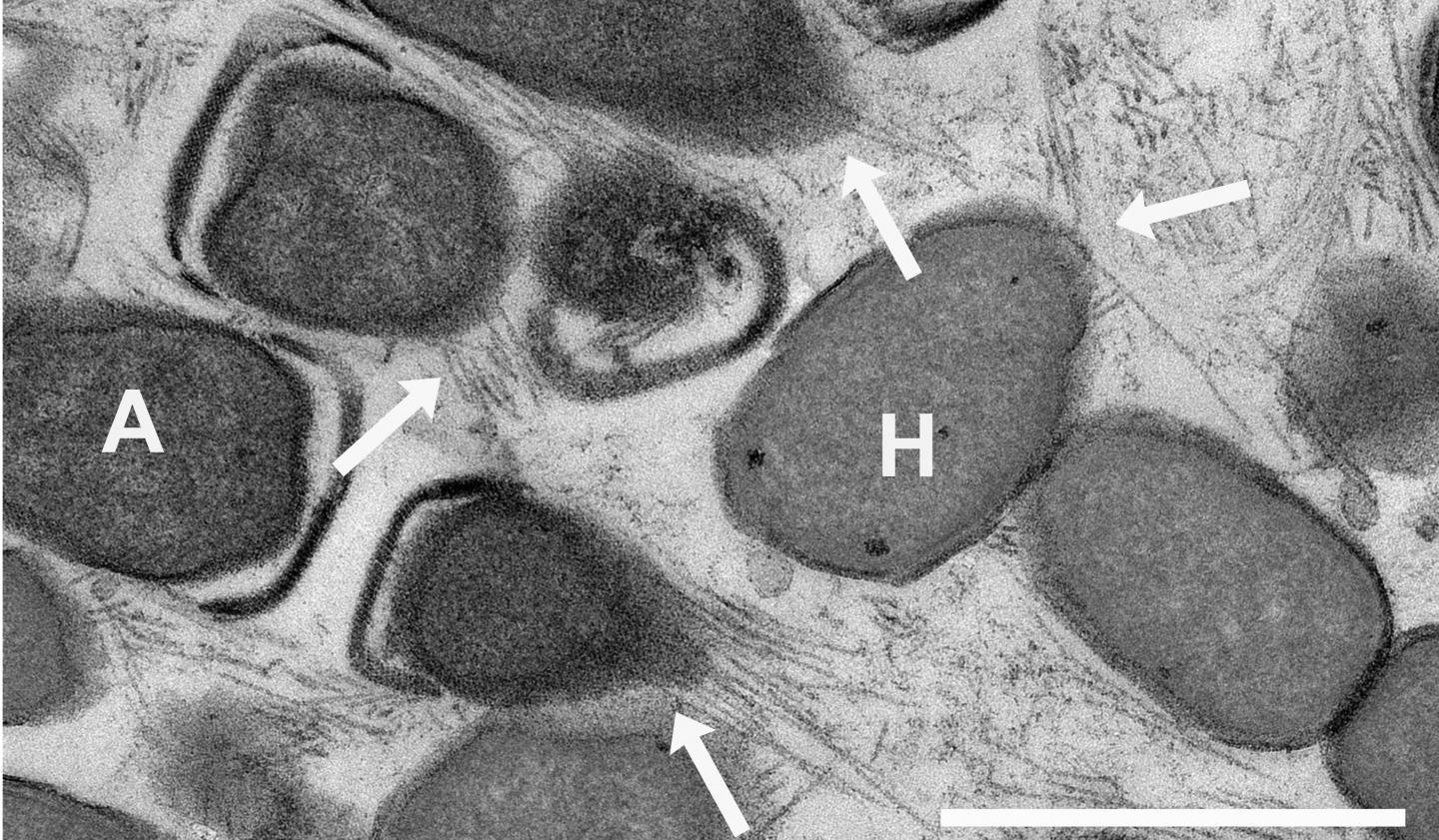

Here’s a sample of Joe Davis’s work,

This photograph shows polyptich paintings by Joe Davis of his 28-mer Microvenus DNA molecule (2006 Exhibition in Greece at Athens School of Fine Arts). Credit: Courtesy of Joe Davis

The news release goes on to recount a brief history of bioart, which stretches back to 1928 and then further back into the 19th and 18th centuries,

In between experiments, Alexander Fleming would paint stick figures and landscapes on paper and in Petri dishes using bacteria. In 1928, after taking a brief hiatus from the lab, he noticed that portions of his “germ paintings,” had been killed. The culprit was a fungus, penicillin–a discovery that would revolutionize medicine for decades to come.

In 1938, photographer Edward Steichen used a chemical to genetically alter and produce interesting variations in flowering delphiniums. This chemical, colchicine, would later be used by horticulturalists to produce desirable mutations in crops and ornamental plants.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the arts and sciences moved away from traditionally shared interests and formed secular divisions that persisted well into the 20th century. “Appearance of environmental art in the 1970s brought about renewed awareness of special relationships between art and the natural world,” Yetisen says.

To demonstrate how we change landscapes, American sculptor Robert Smithsonian paved a hillside with asphalt, while Bulgarian artist Christo Javacheffa (of Christo and Jeanne-Claude) surrounded resurfaced barrier islands with bright pink plastic.

These pieces could sometimes be destructive, however, such as in Ten Turtles Set Free by German-born Hans Haacke. To draw attention to the excesses of the pet trade, he released what he thought were endangered tortoises back to their natural habitat in France, but he inadvertently released the wrong subspecies, thus compromising the genetic lineages of the endangered tortoises as the two varieties began to mate.

By the late 1900s, technological advances began to draw artists’ attention to biology, and by the 2000s, it began to take shape as an artistic identity. Following Joe Davis’ transgenic Microvenus came a miniaturized leather jacket made of skin cells, part of the Tissue Culture & Art Project (initiated in 1996) by duo Oran Catts and Ionat Zurr. Other examples of bioart include: the use of mutant cacti to simulate appearance of human hair in the place of cactus spines by Laura Cinti of University College London’s C-Lab; modification of butterfly wings for artistic purposes by Marta de Menezes of Portugal; and photographs of amphibian deformation by American Brandon Ballengée.

“Bioart encourages discussions about societal, philosophical, and environmental issues and can help enhance public understanding of advances in biotechnology and genetic engineering,” says co-author Ahmet F. Coskun, who works in the Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering at California Institute of Technology.

Life as a Bioartist

Today, Joe Davis is a research affiliate at MIT Biology and “Artist-Scientist” at the George Church Laboratory at Harvard–a place that fosters creativity and technological development around genetic engineering and synthetic biology. “It’s Oz, pure and simple,” Davis says. “The total amount of resources in this environment and the minds that are accessible, it’s like I come to the city of Oz every day.”

But it’s not a one-way street. “My particular lab depends on thinking outside the box and not dismissing things because they sound like science fiction,” says [George M.] Church, who is also part of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering. “Joe is terrific at keeping us flexible and nimble in that regard.”

For example, Davis is working with several members of the Church lab to perform metagenomics analyses of the dust that accumulates at the bottom of money-counting machines. Another project involves genetically engineering silk worms to spin metallic gold–an homage to the fairy tale of Rumpelstiltskin.

“I collaborate with many colleagues on projects that don’t necessarily have direct scientific results, but they’re excited to pursue these avenues of inquiry that they might not or would not look into ordinarily–they might try to hide it, but a lot of scientists have poetic souls,” Davis says. “Art, like science, has to describe the whole word and you can’t describe something you’re basically clueless about. The most exciting part of these activities is satiating overwhelming curiosity about everything around you.”

The number of bioartists is still small, Davis says, partly because of a lack of federal funding of the arts in general. Accessibility to the types of equipment bioartists want to experiment with can also be an issue. While Davis has partnered with labs over the past few decades, other artists affiliate themselves with community access laboratories that are run by do-it-yourself biologists. One way that universities can help is to create departmental-wide positions for bioartists to collaborate with scientists.

“In the past, there have been artists affiliated with departments in a very utilitarian way to produce figures or illustrations,” Church says. “Having someone like Joe stimulates our lab to come together in new ways and if we had more bioartists, I think thinking out of the box would be a more common thing.”

“In the era of genetic engineering, bioart will gain new meanings and annotations in social and scientific contexts,” says Yetisen. “Bioartists will surely take up new roles in science laboratories, but this will be subject to ethical criticism and controversy as a matter of course.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Bioart by Ali K. Yetisen, Joe Davis, Ahmet F. Coskun, George M. Church, Seok Hyun. Trends in Biotechnology, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.09.011 Published Online: November 23, 2015

This paper appears to be open access.

*Removed the word ‘featured’ on Dec. 1, 2015 at 1030 hours PDT.