A ‘buckyball’, for anyone who doesn’t know, is a molecule made up of carbon atoms, Said to resemble soccer balls or geodesic domes, they’re also known as C60 or Buckminsterfullerenes as Rachel Abraham notes in her November 13, 2019 University of Arizona news release (also on EurekAlert),

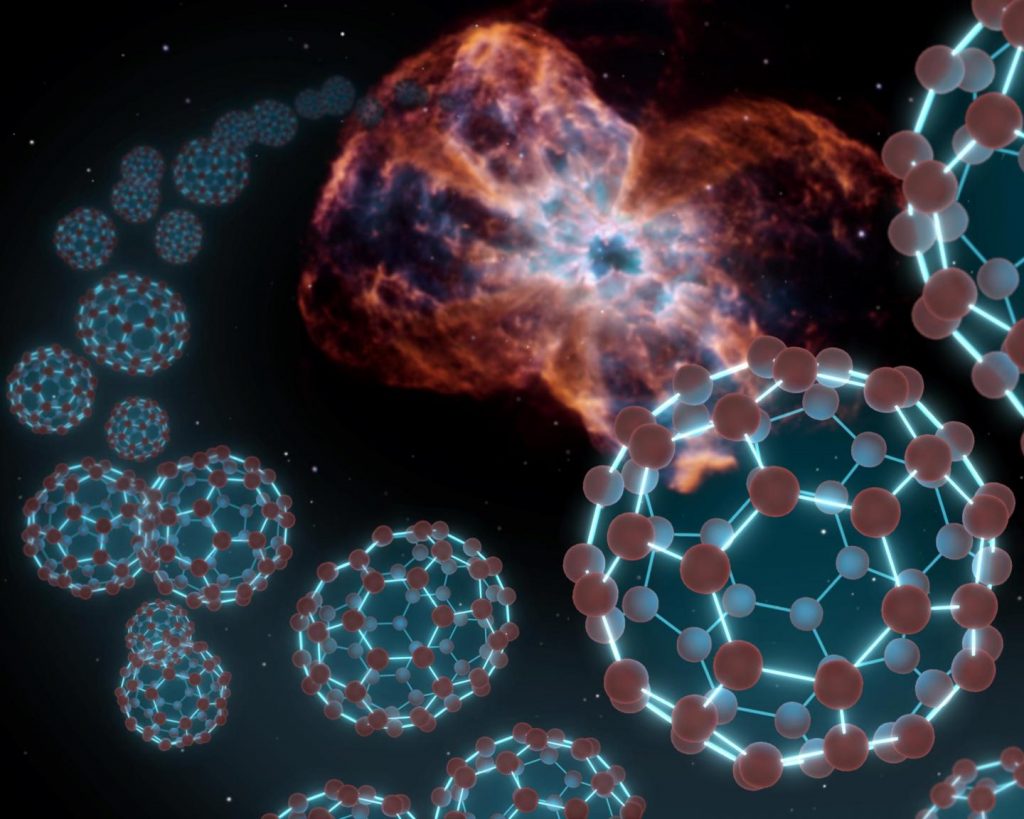

Scientists have long been puzzled by the existence of so-called “buckyballs” – complex carbon molecules with a soccer-ball-like structure – throughout interstellar space. Now, a team of researchers from the University of Arizona has proposed a mechanism for their formation in a study published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Carbon 60, or C60 for short, whose official name is Buckminsterfullerene, comes in spherical molecules consisting of 60 carbon atoms organized in five-membered and six-membered rings. The name “buckyball” derives from their resemblance to the architectural work of Richard Buckminster Fuller [bettr known as Buckminster Fuller], who designed many dome structures that look similar to C60. Their formation was thought to only be possible in lab settings until their detection in space challenged this assumption.

For decades, people thought interstellar space was sprinkled with lightweight molecules only: mostly single atoms, two-atom molecules and the occasional nine or 10-atom molecules. This was until massive C60 and C70 molecules were detected a few years ago.

Researchers were also surprised to find that that they were composed of pure carbon. In the lab, C60 is made by blasting together pure carbon sources, such as graphite. In space, C60 was detected in planetary nebulae, which are the debris of dying stars. This environment has about 10,000 hydrogen molecules for every carbon molecule.

“Any hydrogen should destroy fullerene synthesis,” said astrobiology and chemistry doctoral student Jacob Bernal, lead author of the paper. “If you have a box of balls, and for every 10,000 hydrogen balls you have one carbon, and you keep shaking them, how likely is it that you get 60 carbons to stick together? It’s very unlikely.”

Bernal and his co-authors began investigating the C60 mechanism after realizing that the transmission electron microscope, or TEM, housed at the Kuiper Materials Imaging and Characterization Facility at UArizona, was able to simulate the planetary nebula environment fairly well.

The TEM, which is funded by the National Science Foundation and NASA, has a serial number of “1” because it is the first of its kind in the world with its exact configuration. Its 200,000-volt electron beam can probe matter down to 78 picometers – scales too small for the human brain to comprehend – in order to see individual atoms. It operates under a vacuum with extremely low pressures. This pressure, or lack thereof, in the TEM is very close to the pressure in circumstellar environments.

“It’s not that we necessarily tailored the instrument to have these specific kinds of pressures,” said Tom Zega, associate professor in the UArizona Lunar and Planetary Lab and study co-author. “These instruments operate at those kinds of very low pressures not because we want them to be like stars, but because molecules of the atmosphere get in the way when you’re trying to do high-resolution imaging with electron microscopes.”

The team partnered with the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Lab, near Chicago, which has a TEM capable of studying radiation responses of materials. They placed silicon carbide, a common form of dust made in stars, in the low-pressure environment of the TEM, subjected it to temperatures up to 1,830 degrees Fahrenheit and irradiated it with high-energy xenon ions.

Then, it was brought back to Tucson for researchers to utilize the higher resolution and better analytical capabilities of the UArizona TEM. They knew their hypothesis would be validated if they observed the silicon shedding and exposing pure carbon.

“Sure enough, the silicon came off, and you were left with layers of carbon in six-membered ring sets called graphite,” said co-author Lucy Ziurys, Regents Professor of astronomy, chemistry and biochemistry. “And then when the grains had an uneven surface, five-membered and six-membered rings formed and made spherical structures matching the diameter of C60. So, we think we’re seeing C60.”

This work suggests that C60 is derived from the silicon carbide dust made by dying stars, which is then hit by high temperatures, shockwaves and high energy particles , leeching silicon from the surface and leaving carbon behind. These big molecules are dispersed because dying stars eject their material into the interstellar medium – the spaces in between stars – thus accounting for their presence outside of planetary nebulae. Buckyballs are very stable to radiation, allowing them to survive for billions of years if shielded from the harsh environment of space.

“The conditions in the universe where we would expect complex things to be destroyed are actually the conditions that create them,” Bernal said, adding that the implications of the findings are endless.

“If this mechanism is forming C60, it’s probably forming all kinds of carbon nanostructures,” Ziurys said. “And if you read the chemical literature, these are all thought to be synthetic materials only made in the lab, and yet, interstellar space seems to be making them naturally.”

If the findings are any sign, it appears that there is more the universe has to tell us about how chemistry truly works.

I have two links and citations. This first is for the 2019 paper being described here and the second is the original 1985 paper about C60.

Formation of Interstellar C60 from Silicon Carbide Circumstellar Grains by J. J. Bernal, P. Haenecour, J. Howe, T. J. Zega, S. Amari, and L. M. Ziurys. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, Volume 883, Number 2 Published 2019 October 1 © 2019. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved.

This paper is behind a paywall.

C60: Buckminsterfullerene by H. W. Kroto, J. R. Heath, S. C. O’Brien, R. F. Curl & R. E. Smalley. Nature volume 318, pages162–163 (1985) doi:10.1038/318162a0

This paper is open access.