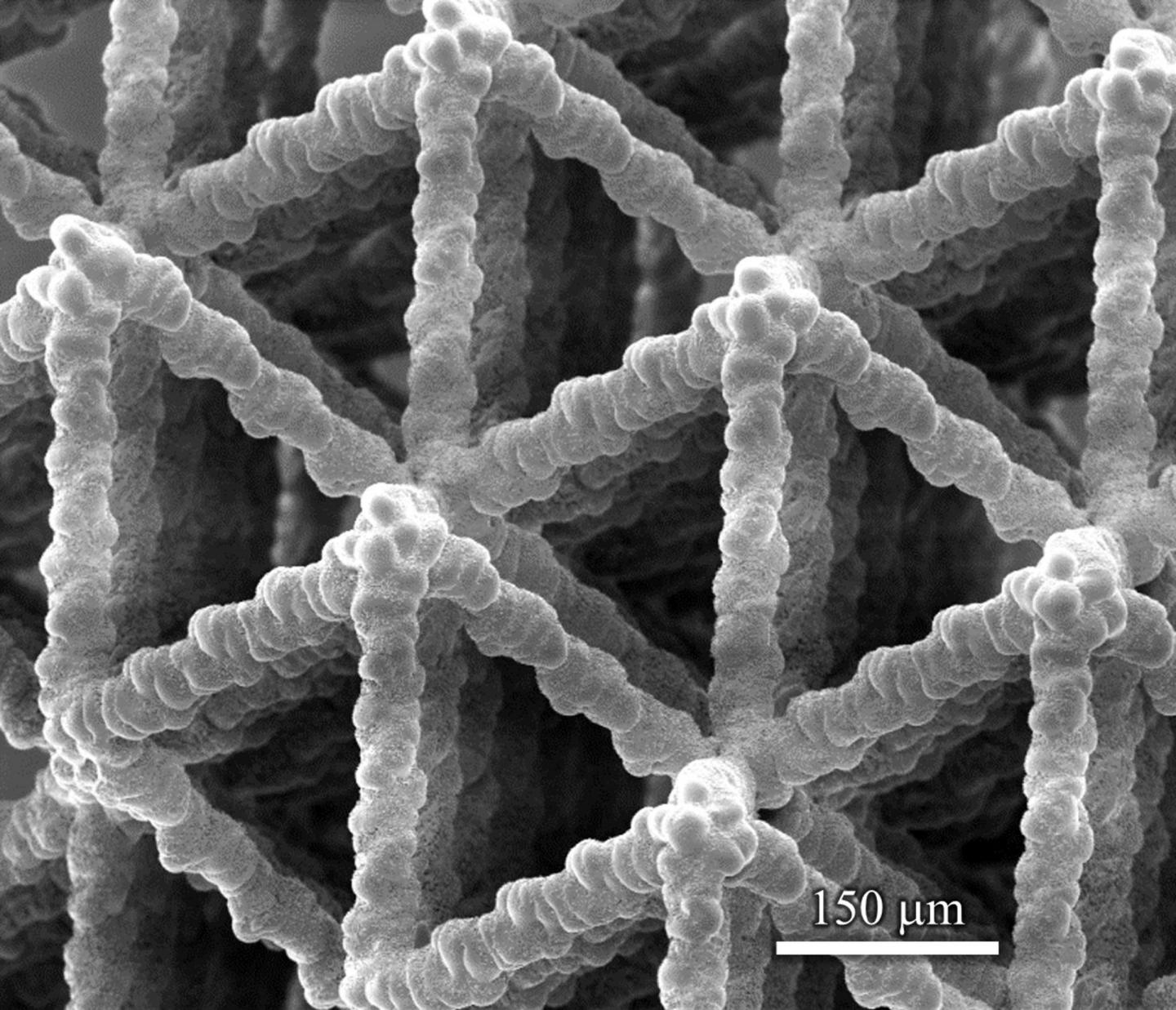

Caption: Microstructures like this one developed at Washington State University could be used in batteries, lightweight ultrastrong materials, catalytic converters, supercapacitors and biological scaffolds. Credit: Washington State University

A March 3, 2017 news item on Nanowerk features a new 3D manufacturing technique for creating biolike materials, (Note: A link has been removed)

Washington State University nanotechnology researchers have developed a unique, 3-D manufacturing method that for the first time rapidly creates and precisely controls a material’s architecture from the nanoscale to centimeters. The results closely mimic the intricate architecture of natural materials like wood and bone.

They report on their work in the journal Science Advances (“Three-dimensional microarchitected materials and devices using nanoparticle assembly by pointwise spatial printing”) and have filed for a patent.

A March 3, 2017 Washington State University news release by Tina Hilding (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

“This is a groundbreaking advance in the 3-D architecturing of materials at nano- to macroscales with applications in batteries, lightweight ultrastrong materials, catalytic converters, supercapacitors and biological scaffolds,” said Rahul Panat, associate professor in the School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering, who led the research. “This technique can fill a lot of critical gaps for the realization of these technologies.”

The WSU research team used a 3-D printing method to create foglike microdroplets that contain nanoparticles of silver and to deposit them at specific locations. As the liquid in the fog evaporated, the nanoparticles remained, creating delicate structures. The tiny structures, which look similar to Tinkertoy constructions, are porous, have an extremely large surface area and are very strong.

Silver was used because it is easy to work with. However, Panat said, the method can be extended to any other material that can be crushed into nanoparticles – and almost all materials can be.

The researchers created several intricate and beautiful structures, including microscaffolds that contain solid truss members like a bridge, spirals, electronic connections that resemble accordion bellows or doughnut-shaped pillars.

The manufacturing method itself is similar to a rare, natural process in which tiny fog droplets that contain sulfur evaporate over the hot western Africa deserts and give rise to crystalline flower-like structures called “desert roses.”

Because it uses 3-D printing technology, the new method is highly efficient, creates minimal waste and allows for fast and large-scale manufacturing.

The researchers would like to use such nanoscale and porous metal structures for a number of industrial applications; for instance, the team is developing finely detailed, porous anodes and cathodes for batteries rather than the solid structures that are now used. This advance could transform the industry by significantly increasing battery speed and capacity and allowing the use of new and higher energy materials.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Three-dimensional microarchitected materials and devices using nanoparticle assembly by pointwise spatial printing by Mohammad Sadeq Saleh, Chunshan Hu, and Rahul Panat. Science Advances 03 Mar 2017: Vol. 3, no. 3, e1601986 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1601986

This paper appears to be open access.

Finally, there is a video,