I gather Chris Landreth’s short animation, Subconscious Password, hasn’t been officially released yet by the National Film Board (NFB) of Canada but there are clips and trailers which hint at some of the filmmaker’s themes. Landreth in a May 23, 2013 guest post for the NFB.ca blog spells out one of them,

Subconscious Password, my latest short film, travels to the inner mind of a fellow named Charles Langford, as he struggles to remember the name of his friend at a party. In his subconscious, he encounters a game show, populated with special guest stars: archetypes, icons, distant memories, who try to help him find the connection he needs: His friend’s name.

The film is a psychological romp into a person’s inner mind where (I hope) you will see something of your own mind working, thinking, feeling. Even during a mundane act like remembering the name of an acquaintance at a party, someone you only vaguely remember. To me, mundane accomplishments like these are miracles we all experience many times each day.

Landreth also discusses the ‘uncanny valley’ and how he deliberately cast his film into that valley. For anyone who’s unfamiliar with the ‘uncanny valley’ I wrote about it in a Mar. 10, 2011 posting concerning Geminoid robots,

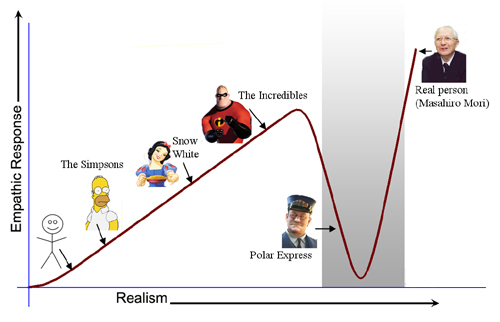

It seems that researchers believe that the ‘uncanny valley’ doesn’t necessarily have to exist forever and at some point, people will accept humanoid robots without hesitation. In the meantime, here’s a diagram of the ‘uncanny valley’,

From the article on Android Science by Masahiro Mori (translated by Karl F. MacDorman and Takashi Minato)

Here’s what Mori (the person who coined the term) had to say about the ‘uncanny valley’ (from Android Science),

Recently there are many industrial robots, and as we know the robots do not have a face or legs, and just rotate or extend or contract their arms, and they bear no resemblance to human beings. Certainly the policy for designing these kinds of robots is based on functionality. From this standpoint, the robots must perform functions similar to those of human factory workers, but their appearance is not evaluated. If we plot these industrial robots on a graph of familiarity versus appearance, they lie near the origin (see Figure 1 [above]). So they bear little resemblance to a human being, and in general people do not find them to be familiar. But if the designer of a toy robot puts importance on a robot’s appearance rather than its function, the robot will have a somewhat humanlike appearance with a face, two arms, two legs, and a torso. This design lets children enjoy a sense of familiarity with the humanoid toy. So the toy robot is approaching the top of the first peak.

Of course, human beings themselves lie at the final goal of robotics, which is why we make an effort to build humanlike robots. For example, a robot’s arms may be composed of a metal cylinder with many bolts, but to achieve a more humanlike appearance, we paint over the metal in skin tones. These cosmetic efforts cause a resultant increase in our sense of the robot’s familiarity. Some readers may have felt sympathy for handicapped people they have seen who attach a prosthetic arm or leg to replace a missing limb. But recently prosthetic hands have improved greatly, and we cannot distinguish them from real hands at a glance. Some prosthetic hands attempt to simulate veins, muscles, tendons, finger nails, and finger prints, and their color resembles human pigmentation. So maybe the prosthetic arm has achieved a degree of human verisimilitude on par with false teeth. But this kind of prosthetic hand is too real and when we notice it is prosthetic, we have a sense of strangeness. So if we shake the hand, we are surprised by the lack of soft tissue and cold temperature. In this case, there is no longer a sense of familiarity. It is uncanny. In mathematical terms, strangeness can be represented by negative familiarity, so the prosthetic hand is at the bottom of the valley. So in this case, the appearance is quite human like, but the familiarity is negative. This is the uncanny valley.

Landreth discusses the ‘uncanny valley’ in relation to animated characters,

Many of you know what this is. The Uncanny Valley describes a common problem that audiences have with CG-animated characters. Here’s a graph that shows this:

Follow the curvy line from the lower left. If a character is simple (like a stick figure) we have little or no empathy with it. A more complex character, like Snow White orPixar’s Mr. Incredible, gives us more human-like mannerisms for us to identify with.

But then the Uncanny Valley kicks in. That curvy line changes direction, plunging downwards. This is the pit into which many characters from The Polar Express, Final Fantasy and Mars Needs Moms fall. We stop empathizing with these characters. They are unintentionally disturbing, like moving corpses. This is a big problem with realistic CGI characters: that unshakable perception that they are animated zombies. [zombie emphasis mine]

You’ll notice that the diagram from my posting features a zombie at the very bottom of the curve.

Landreth goes on to compare the ‘land’ in the uncanny valley to real estate,

… The value of land in the Uncanny Valley has plunged to zero. There are no buyers.

Well, except perhaps me.

Some of you know that my films have a certain obsession with visual realism with their human characters. I like doing this. I find value in this realism that goes beyond simply copying what humans look and act like. If used intelligently and with imagination, realism can capture something deeper, something weird and emotional and psychological about our collective experience on this planet. But it has to be honest. That’s hard.

He also explains what he’s hoping to accomplish by inhabiting the uncanny valley,

When making this film, we knew we were going into the Uncanny Valley. We did it because your subconscious processes, and mine, are like this valley. We project our waking world into our subconscious minds. The ‘characters’ in this inner world are realistic approximations of actual people, without actually being real. This is the miracle of how we get by. My protagonist, Charles, has a mixture of both realistic approximations and crazy warped versions of the people and icons in his life. He is indeed a bit off-kilter. But he gets by, like most of us do. As you probably have guessed, both Charles and the Host are self-portraits. I want to be honest in showing you this world. My own Uncanny Valley. You have one too. It’s something to celebrate.

On the that note, here’s a clip from Subconscious Password,

Subconscious Password (Clip) by Chris Landreth, National Film Board of Canada

I last wrote about Landreth and his work in an April 14, 2010 posting (scroll down about 1/4 of the way) regarding mathematics and the arts. This post features excerpts from an interview with the University of Toronto (Ontario, Canada) mathematician, Karan Singh who worked with Landreth on their award-winning, Ryan.