A mixed team of Danish and Chinese scientists have made a transistor from a single molecular monolayer that works on a computer chip according to a June 19, 2013 University of Copenhagen news release,

The molecular integrated circuit was created by a group of chemists and physicists from the Department of Chemistry Nano-Science Center at the University of Copenhagen and Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing. Their discovery “Ultrathin Reduced Graphene Oxide Films as Transparent Top-Contacts for Light Switchable Solid-State Molecular Junctions” has just been published online in the prestigious periodical Advanced Materials. The breakthrough was made possible through an innovative use of the two dimensional carbon material graphene.

Here’s how the transistor works (from the news release),

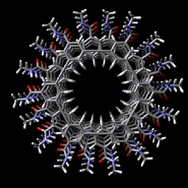

The molecular computer chip is a sandwich built with one layer of gold, one of molecular components and one of the extremely thin carbon material graphene. The molecular transistor in the sandwich is switched on and of using a light impulse so one of the peculiar properties of graphene is highly useful. Even though graphene is made of carbon, it’s almost completely translucent.

…

Using the new graphene chip researchers can now place their molecules with great precision. This makes it faster and easier to test the functionality of molecular wires, contacts and diodes so that chemists will know in no time whether they need to get back to their beakers to develop new functional molecules, explains Nørgaard [Kasper Nørgaard, an associate professor in chemistry at the University of Copenhagen].

“We’ve made a design, that’ll hold many different types of molecule” he says and goes on: “Because the graphene scaffold is closer to real chip design it does make it easier to test components, but of course it’s also a step on the road to making a real integrated circuit using molecular components. And we must not lose sight of the fact that molecular components do have to end up in an integrated circuit, if they are going to be any use at all in real life”.

In addition to the other benefits of this graphene chip, greater precision, etc., it is also greener, requiring no rare earths or heavy metals.

If you have problems accessing the news release, you can find the information in a June 20, 2013 news item on Nanowerk.