Canada is the 10th largest (1.2%) producer of graphite in the world with China leading the way in the top spot at 68.1%. That’s right, 1.2% can get you into the top 10.

If you’re curious about which countries fill out the other eight spots, The National Research Council of Canada has a handy webpage titled, Graphite Facts,

Graphite is a non-metallic mineral that has properties similar to metals, such as a good ability to conduct heat and electricity. Graphite occurs naturally or can be produced synthetically. Purified natural graphite has higher crystalline structure and offers better electrical and thermal conductivity than synthetic material.

…

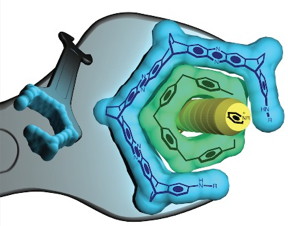

Among the many applications, natural and synthetic graphite are used for electrodes, refractories, batteries and lubricants and by foundries. Coated spherical graphite is used to manufacture the anode in lithium-ion batteries. High-grade graphite is also used in fuel cells, semiconductors, LEDs and nuclear reactors.

…

The Lac des Iles mine is the only mine in Canada that is producing graphite. However, many other companies are working on graphite projects.

Canada’s graphite shipments reached 11,937 tonnes in 2020, up slightly from 11,045 tonnes in 2020 [sic].

…

Global production and demand for graphite are anticipated to increase in the coming years, largely because of the use of graphite in the batteries of electric vehicles. In 2020, global consumption of graphite reached 2.7 million tonnes. Synthetic graphite accounted for about two-thirds of the graphite consumption, which was largely concentrated in Asia.

…

In 2020, the value of Canada’s exports of graphite was $31.6 million, a 9% decrease compared to the previous year. Imports also decreased in 2020, by 33% to $20.9 million.

Natural graphite accounted for 46.7% ($14.8 million) of the value of Canada’s exports of graphite and 13.5% ($2.8 million) of Canada’s imports of graphite in 2020. Synthetic graphite accounted for 53.3% ($ 16.9 million) of Canada’s exports of graphite and 86.5% ($18.0 million) of Canada’s imports of graphite in 2020.

In 2020, the United States was the primary destination for Canada’s exports of natural and synthetic graphite, accounting for 85% and 42% of the total exports, respectively.

…

I think the writer meant that shipments were up slightly from 2019. The page was last updated on February 4, 2022.

The news from Ohio

A June 10, 2022 news item on Nanowerk about research into a new type of graphite (Note: A link has been removed),

As the world’s appetite for carbon-based materials like graphite increases, Ohio University researchers presented evidence this week for a new carbon solid they named “amorphous graphite.”

Physicist David Drabold and engineer Jason Trembly started with the question, “Can we make graphite from coal?”

“Graphite is an important carbon material with many uses. A burgeoning application for graphite is for battery anodes in lithium-ion batteries, and it is crucial for the electric vehicle industry — a Tesla Model S on average needs 54 kg of graphite. Such electrodes are best if made with pure carbon materials, which are becoming more difficult to obtain owing to spiraling technological demand,” they write in their paper that published in Physical Review Letters (“Ab initio simulation of amorphous graphite”).

Ab initio means from the beginning, and their work pursues novel paths to synthetic forms of graphite from naturally occurring carbonaceous material. What they found, with several different calculations, was a layered material that forms at very high temperatures (about 3000 degrees Kelvin). Its layers stay together due to the formation of an electron gas between the layers, but they’re not the perfect layers of hexagons that make up ideal graphene. This new material has plenty of hexagons, but also pentagons and heptagons. That ring disorder reduces the electrical conductivity of the new material compared with graphene, but the conductivity is still high in the regions dominated largely by hexagons.

…

A June 10, 2022 Ohio University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, delves further into the research (Note: Links have been removed),

Not all hexagons

“In chemistry, the process of converting carbonaceous materials to a layered graphitic structure by thermal treatment at high temperature is called graphitization. In this letter, we show from ab initio and machine learning molecular dynamic simulations that pure carbon networks have an overwhelming proclivity to convert to a layered structure in a significant density and temperature window with the layering occurring even for random starting configurations. The flat layers are amorphous graphene: topologically disordered three-coordinated carbon atoms arranged in planes with pentagons, hexagons and heptagons of carbon,” said Drabold, Distinguished Professor of Physics and Astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences at Ohio University.

“Since this phase is topologically disordered, the usual ‘stacking registry’ of graphite is only statistically respected,” Drabold said. “The layering is observed without Van der Waals corrections to density functional (LDA and PBE) forces, and we discuss the formation of a delocalized electron gas in the galleries (voids between planes) and show that interplane cohesion is partly due to this low-density electron gas. The in-plane electronic conductivity is dramatically reduced relative to graphene.”

The researchers expect their announcement to spur experimentation and studies addressing the existence of amorphous graphite, which may be testable from exfoliation and/or experimental surface structural probes.

Trembly, Russ Professor of Mechanical Engineering and director of the Institute for Sustainable Energy and the Environment in the Russ College of Engineering and Technology at Ohio University, has been working in part on green uses of coal. He and Drabold — along with physics doctoral students Rajendra Thapa, Chinonso Ugwumadu and Kishor Nepal — collaborated on the research. Drabold also is part of the Nanoscale & Quantum Phenomena Institute at OHIO, and he has published a series of papers on the theory of amorphous carbon and amorphous graphene. Drabold also emphasized the excellent work of his graduate students in carrying out this research.

Surprising interplane cohesion

“The question that led us to this is whether we could make graphite from coal,” Drabold said. “This paper does not fully answer that question, but it shows that carbon has an overwhelming tendency to layer — like graphite, but with many ‘defects’ such as pentagons and heptagons (five- and seven-member rings of carbon atoms), which fit quite naturally into the network. We present evidence that amorphous graphite exists, and we describe its process of formation. It has been suspected from experiments that graphitization occurs near 3,000K, but the details of the formation process and nature of disorder in the planes was unknown,” he added.

The Ohio University researchers’ work is also a prediction of a new phase of carbon.

“Until we did this, it was not at all obvious that layers of amorphous graphene (the planes including pentagons and heptagons) would stick together in a layered structure. I find that quite surprising, and it is likely that experimentalists will go hunting for this stuff now that its existence is predicted,” Drabold said. “Carbon is the miracle element — you can make life, diamond, graphite, Bucky Balls, nanotubes, graphene, [emphasis mine] and now this. There is a lot of interesting basic physics in this, too — for example how and why the planes bind, this by itself is quite surprising for technical reasons.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Ab Initio Simulation of Amorphous Graphite by R. Thapa, C. Ugwumadu, K. Nepal, J. Trembly, and D. A. Drabold. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 236402 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.236402 Published 10 June 2022 © 2022 American Physical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

There is an earlier version of the paper which is open access at ArXiv (hosted by Cornell University),

[Submitted on 22 Feb 2022 (v1), last revised 23 Apr 2022 (this version, v2)]

Ab initio simulation of amorphous graphite by Rajendra Thapa, Chinonso Ugwumadu, Kishor Nepal, Jason Trembly, David Drabold

About graphite and Canadian mines

A July 25, 2011 posting marks the earliest appearance of graphite on this blog. Titled, “Canadians as hewers of graphite?” It featured Northern Graphite Corporation, which today (June 21, 2022) is the largest North American graphite producer according to the company’s homepage,

- Only North American producer

- Will be 3rd largest non-Chinese producer

- Two large development projects

- All projects:

- In politically stable countries

- Have “battery quality” graphite

- Close to infrastructure

There’s also this from the company’s homepage,

Northern owns the Lac des Iles (LDI) mine in Quebec, the only significant graphite producer in North America. Northern plans to increase production and extend the mine life.

Northern is currently upgrading its Okorusu processing plant in Namibia. It will be back on line in 1H 2023 and make Northern the third largest non Chinese graphite producer.

Northern plans to develop its advanced stage Bissett Creek project in Ontario which has a full Feasibility Study. It has been rated as the highest margin graphite deposit in the world.

The Okanjande deposit in Namibia has a very large measured and indicated resource. Northern intends to study building a 150,000tpa plant to supply battery markets in Europe.

I notice the involvement in Namibia. I hope this is a ‘good’ mining company. Canadian mining companies have been known to breach human rights and environmental regulations when operating internationally. There’s a recent tragedy described in this June 20, 2020 news article on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) online news site (Note: A link has been removed),

Trevali Mining Corp. says it has recovered the bodies of the final two of eight workers killed after its Perkoa Mine in Burkina Faso flooded following heavy rainfall on Apr. 16 [2022].

The bodies of the other six workers were recovered by search teams late last month.

…

The Vancouver-based zinc miner says it is working alongside Burkinabe authorities to coordinate the dewatering and rehabilitation of the mine.

The flooding event is under investigation by the company and government authorities.

MiningWatch Canada, an Ottawa-based industry watchdog, has questioned how well the company was prepared for disaster and criticized the federal government’s lack of regulations on how Canadian mining companies operate internationally. [emphasis mine]

They say tighter rules are necessary for companies operating abroad.

…

A May 10, 2022 article by Amanda Follett Hosgood about the disaster for The Tyee provides more details and asks some very pertinent and uncomfortable questions. (Yes, The Tyee is a very ‘left wing’ journalistic effort and they have a point where Canadian mining companies are concerned.)

Getting back to Northern Graphite, there’s this from their Governance page,

Northern Graphite is committed to conducting its activities in a manner that meets best international industry practices regardless of the country or location of operation. The Company will operate with the highest standards of honesty, integrity, and ethical behaviour. It will conduct its business in a manner that meets or exceeds all applicable laws, rules, and regulations and meets its social and moral obligations. This policy applies to all Board members, officers and other employees, contractors, and other third parties working on behalf of or representing the Company.

…

The company gets more specific, from their Governance page,

- …

- Taking all reasonable precautions to ensure the health and safety of workers and others affected by the Company’s operations.

- Managing and minimizing the environmental impact of the Company’s operations by following best international practices and standards and meeting stakeholder expectations while recognizing that mining will always have some unavoidable impacts on the environment.

- Utilizing practices and technologies that minimize the Company’s water and carbon footprints.

- …

- Respecting the rights, culture and development of local and Indigenous communities.

- …

- The elimination of fraud, bribery, and corruption.

- The protection and respect of human rights.

- …

- Providing an adequate return to shareholders and investors while ensuring that all stakeholders benefit from the extraction of the earth’s resources through fair labour and compensation practices, local hiring and contracting, community support, and the payment of all applicable government taxes and royalties.

There are two other Canadian mining companies (that I know of) in pursuit of graphite, Lomiko Metals (British Columbia) and Focus Graphite (Ontario). All the mines in Canada, whether they are producing or not, are in either Québec or Ontario.

As for the research team in Ohio, congratulations on your very exciting work!