An October 16, 2019 news item on Nanowerk announces some of the latest work with colloidal quantum dots,

Researchers of the Optoelectronics and Measurement Techniques Unit (OPEM) at the University of Oulu [Finland] have invented a new method of producing ultra-sensitive hyper-spectral photodetectors. At the heart of the discovery are colloidal quantum dots, developed together with the researchers at the University of Toronto, Canada.

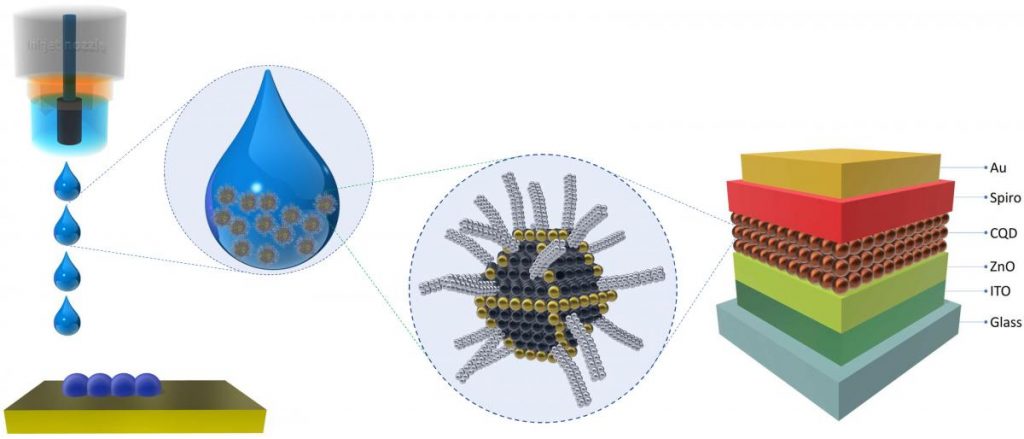

Quantum dots are tiny particles of 15-150 atoms of semiconducting material that have extraordinary optical and electrical properties due to quantum mechanics phenomena.

By controlling the size of the dots, the researchers are able to finetune how they react to different light colors (light wavelengths), especially those invisible for the human eye, namely the infrared spectrum.

…

An October 16, 2019 Oulu University press release, which originated the news item, provides more detail,

-Naturally, it is very rewarding that our hard work has been recognized by the international scientific community but at the same time, this report helps us to realize that there is a long journey ahead in incoming years. This publication is especially satisfying because it is the result of collaboration with world-class experts at the University of Toronto, Canada. This international collaboration where we combined the expertise of Toronto’s researchers in synthesizing quantum dots and our expertise in printed intelligence resulted in truly unique devices with astonishing performance, says docent Rafal Sliz, a leading researcher in this project.

Mastered in the OPEM unit, inkjet printing technology makes possible the creation of optoelectronic devices by designing functional inks that are printed on various surfaces, for instance, flexible substrates, clothing or human skin. Inkjet printing combined with colloidal quantum dots allowed the creation of photodetectors of impresive detectivity characteristics. The developed technology is a milestone in the creation of a new type of sub-micron-thick, flexible, and inexpensive IR sensing devices, the next generation of solar cells and other novel photonic systems.-Oulus’ engineers and scientists’ strong expertise in optoelectronics resulted in many successful Oulu-based companies like Oura, Specim, Focalspec, Spectral Engines, and many more. New optoelectronic technologies, materials, and methods developed by our researchers will help Oulu and Finland to stay at the cutting edge of innovation, says professor Tapio Fabritius, a leader of the OPEM.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Stable Colloidal Quantum Dot Inks Enable Inkjet-Printed High-Sensitivity Infrared Photodetectors by Rafal Sliz, Marc Lejay, James Z. Fan, Min-Jae Choi, Sachin Kinge, Sjoerd Hoogland, Tapio Fabritius, F. Pelayo García de Arquer, Edward H. Sargent. ACS Nano 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b06125 Publication Date:September 23, 2019 Copyright © 2019 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.