An Oct. 24, 2016 phys.org news item describes research which may lead to improved fuel storage in ‘green’ cars,

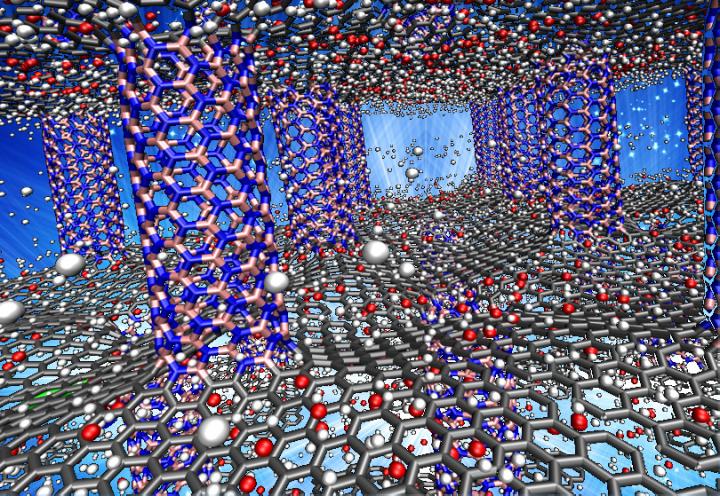

Layers of graphene separated by nanotube pillars of boron nitride may be a suitable material to store hydrogen fuel in cars, according to Rice University scientists.

The Department of Energy has set benchmarks for storage materials that would make hydrogen a practical fuel for light-duty vehicles. The Rice lab of materials scientist Rouzbeh Shahsavari determined in a new computational study that pillared boron nitride and graphene could be a candidate.

An Oct. 24, 2016 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more detail (Note: Links have been removed),

Shahsavari’s lab had already determined through computer models how tough and resilient pillared graphene structures would be, and later worked boron nitride nanotubes into the mix to model a unique three-dimensional architecture. (Samples of boron nitride nanotubes seamlessly bonded to graphene have been made.)

Just as pillars in a building make space between floors for people, pillars in boron nitride graphene make space for hydrogen atoms. The challenge is to make them enter and stay in sufficient numbers and exit upon demand.

In their latest molecular dynamics simulations, the researchers found that either pillared graphene or pillared boron nitride graphene would offer abundant surface area (about 2,547 square meters per gram) with good recyclable properties under ambient conditions. Their models showed adding oxygen or lithium to the materials would make them even better at binding hydrogen.

They focused the simulations on four variants: pillared structures of boron nitride or pillared boron nitride graphene doped with either oxygen or lithium. At room temperature and in ambient pressure, oxygen-doped boron nitride graphene proved the best, holding 11.6 percent of its weight in hydrogen (its gravimetric capacity) and about 60 grams per liter (its volumetric capacity); it easily beat competing technologies like porous boron nitride, metal oxide frameworks and carbon nanotubes.

At a chilly -321 degrees Fahrenheit, the material held 14.77 percent of its weight in hydrogen.

The Department of Energy’s current target for economic storage media is the ability to store more than 5.5 percent of its weight and 40 grams per liter in hydrogen under moderate conditions. The ultimate targets are 7.5 weight percent and 70 grams per liter.

Shahsavari said hydrogen atoms adsorbed to the undoped pillared boron nitride graphene, thanks to weak van der Waals forces. When the material was doped with oxygen, the atoms bonded strongly with the hybrid and created a better surface for incoming hydrogen, which Shahsavari said would likely be delivered under pressure and would exit when pressure is released.

“Adding oxygen to the substrate gives us good bonding because of the nature of the charges and their interactions,” he said. “Oxygen and hydrogen are known to have good chemical affinity.”

He said the polarized nature of the boron nitride where it bonds with the graphene and the electron mobility of the graphene itself make the material highly tunable for applications.

“What we’re looking for is the sweet spot,” Shahsavari said, describing the ideal conditions as a balance between the material’s surface area and weight, as well as the operating temperatures and pressures. “This is only practical through computational modeling, because we can test a lot of variations very quickly. It would take experimentalists months to do what takes us only days.”

He said the structures should be robust enough to easily surpass the Department of Energy requirement that a hydrogen fuel tank be able to withstand 1,500 charge-discharge cycles.

Shayeganfar [Farzaneh Shayeganfar], a former visiting scholar at Rice, is an instructor at Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University in Tehran, Iran.

Caption: Simulations by Rice University scientists show that pillared graphene boron nitride may be a suitable storage medium for hydrogen-powered vehicles. Above, the pink (boron) and blue (nitrogen) pillars serve as spacers for carbon graphene sheets (gray). The researchers showed the material worked best when doped with oxygen atoms (red), which enhanced its ability to adsorb and desorb hydrogen (white). Credit: Lei Tao/Rice University

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Oxygen and Lithium Doped Hybrid Boron-Nitride/Carbon Networks for Hydrogen Storage by Farzaneh Shayeganfar and Rouzbeh Shahsavari. Langmuir, DOI: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b02997 Publication Date (Web): October 23, 2016

Copyright © 2016 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

I last featured research by Shayeganfar and Shahsavari on graphene and boron nitride in a Jan. 14, 2016 posting.