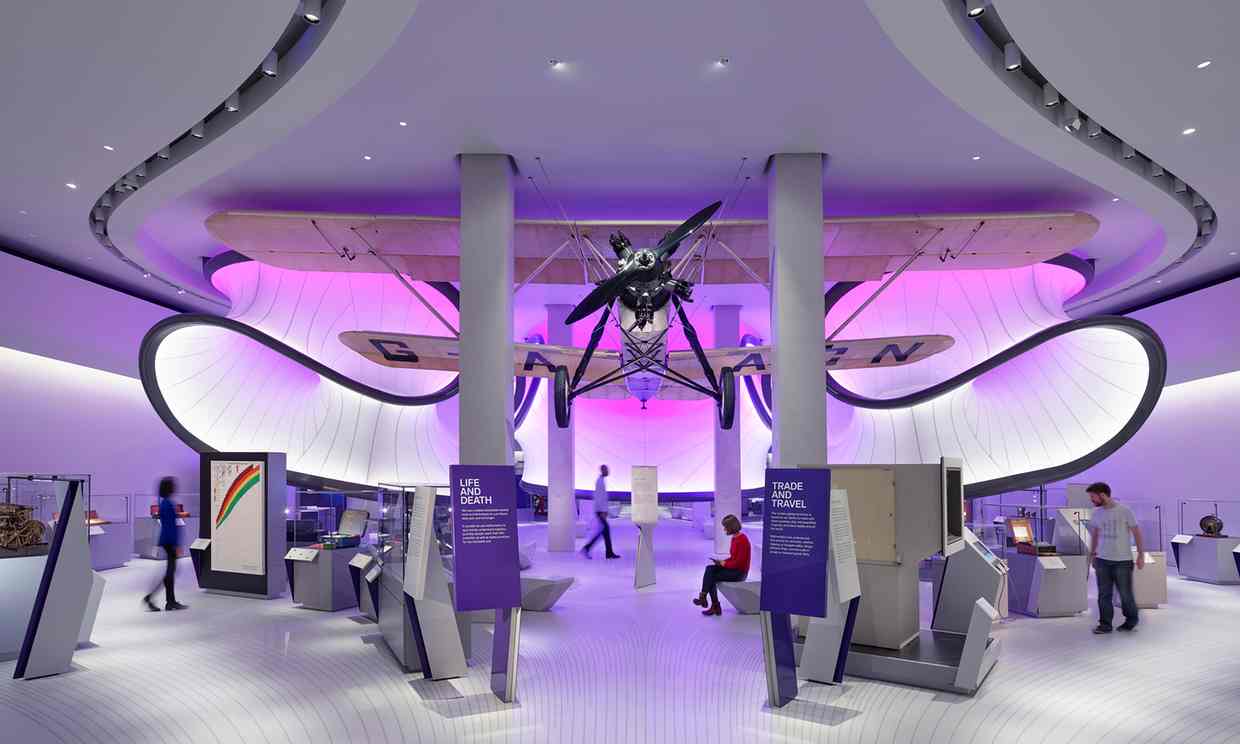

Mathematics: The Winton Gallery at the Science Museum, Zaha Hadid Architects’ only permanent public museum exhibition design. London. Photograph: Nicholas Guttridge/NIck Guttridge

This exhibition looks great in the picture, I wonder what the experience is like. Alex Bellos is certainly enthusiastic in his Dec. 7, 2016 posting on the Guardian’s website,

Mathematics underlies all science, so for a science museum to be worthy of the name, maths needs to included somewhere. Yet maths, which deals mainly in abstract objects, is [a] challenge for museums, which necessarily contain physical ones. The Science Museum’s approach in its new gallery is to tell historical stories about the influence of mathematics in the real world, rather than actually focussing directly on the mathematical ideas involved. The result is a stunning gallery, with fascinating objects beautifully laid out, yet which eschews explaining any maths. (If you want to learn simple mathematical ideas, you can always head to the museum’s new interactive gallery, Wonderlab).

Much of the attention on Mathematics: The Winton Gallery – the main funders are David Harding, founder and CEO of investment firm Winton, and his wife Claudia – has been on Zaha Hadid’s design. The gallery is the first UK project by Zaha Hadid Architects to open since her unexpected death in March [2016], and the only permanent public museum exhibition she designed. Her first degree was in maths, before she turned to architecture.

Hanging from the ceiling is an aeroplane – the Handley Page ‘Gugnunc’, built in 1929 for a competition to build safe aircraft – and surrounding it is a swirly ceiling sculpture that represents the mathematical equations that describe airflow. In fact, the entire gallery follows the contours of the flow, providing the positions of the cabinets below.

…

The Science Museum’s previous maths gallery, which had not been updated in decades, contained about 600 objects, including cabinets crammed with geometrical objects and many examples of the same thing, such as medieval slide rules or Victorian curve-drawing machines. The new gallery has less than a quarter of that number of objects in the same space.

Every object now is in its own cabinet, and the extra space means you can walk around them from all angles, as well as making the gallery feel more manageable. Rather than being bombarded with stuff, you are given a single object to contemplate that tells part of a wider story.

In a section on “form and beauty”, there is a modern replica of a 1920s chair based on French architect’s Le Corbusier’s Modulor system of proportions, and two J W Turner sketches from his Royal Academy lectures on perspective.

The section “trade and travel” has a 3-metre long replica of the 1973 Globtik Tokyo oil tanker, then the largest ship in the world. In its massive cabinet it looks as terrifying as a Damien Hirst shark. The maths link? Because British mathematician William Froode a century before had worked out that bulbous bows were better than sharp bows at the fronts of boats and ships.

…

The new maths gallery is a wonderfully attractive space, full of interesting and thought-provoking objects, and a very welcome addition [geddit?] to London’s museums. Go!

A Dec. 8 (?), 2016 [London, UK] Science Museum press release is the first example I’ve seen of the funders being highlighted quite so prominently, i.e., before the press release proper,

Mathematics: The Winton Gallery designed by Zaha Hadid Architects opens at the Science Museum

- A stunning new permanent gallery that reveals the importance of mathematics in all our lives through remarkable historical artefacts, stories and design

- Free to visit and open daily from 8 December 2016

- The only permanent public museum exhibition designed by Zaha Hadid anywhere in the world

Principal Funder: David and Claudia Harding

Principal Sponsor: Samsung

Major Sponsor: MathWorksOn 8 December 2016 the Science Museum will open an inspirational new mathematics gallery, designed by Zaha Hadid Architects.

Mathematics: The Winton Gallery brings together remarkable stories, historical artefacts and design to highlight the central role of mathematical practice in all our lives, and explores how mathematicians, their tools and ideas have helped build the modern world over the past four centuries.

More than 100 treasures from the Science Museum’s world-class science, technology, engineering and mathematics collections have been selected to tell powerful stories about how mathematics has shaped, and been shaped by, some of our most fundamental human concerns – from trade and travel to war, peace, life, death, form and beauty.

Curator Dr David Rooney said, ‘At its heart this gallery reveals a rich cultural story of human endeavour that has helped transform the world over the last four hundred years. Mathematical practice underpins so many aspects of our lives and work, and we hope that bringing together these remarkable stories, people and exhibits will inspire visitors to think about the role of mathematics in a new light.’

Positioned at the centre of the gallery is the Handley Page ‘Gugnunc’ aeroplane, built in 1929 for a competition to construct safe aircraft. Ground-breaking aerodynamic research influenced the wing design of this experimental aeroplane, helping to shift public opinion about the safety of flying and to secure the future of the aviation industry. This aeroplane encapsulates the gallery’s overarching theme, illustrating how mathematical practice has helped solve real-world problems and in this instance paved the way for the safe passenger flights that we rely on today.

Mathematics also defines Zaha Hadid Architects’ enlightening design for the gallery. Inspired by the Handley Page aircraft, the design is driven by equations of airflow used in the aviation industry. The layout and lines of the gallery represent the air that would have flowed around this historic aircraft in flight, from the positioning of the showcases and benches to the three-dimensional curved surfaces of the central pod structure.

Mathematics: The Winton Gallery is the first permanent public museum exhibition designed by Zaha Hadid Architects anywhere in the world. The gallery is also the first of Zaha Hadid Architects’ projects to open in the UK since Dame Zaha Hadid’s sudden death in March 2016. The late Dame Zaha first became interested in geometry while studying mathematics at university. Mathematics and geometry have a strong connection with architecture and she continued to examine these relationships throughout each of her projects; with mathematics always central to her work. As Dame Zaha said, ‘When I was growing up in Iraq, math was an everyday part of life. We would play with math problems just as we would play with pens and paper to draw – math was like sketching.’

Ian Blatchford, Director of the Science Museum Group, said, ‘We were hugely impressed by the ideas and vision of the late Dame Zaha Hadid and Patrik Schumacher when they first presented their design for the new mathematics gallery over two years ago. It was a terrible shock for us all when Dame Zaha died suddenly in March this year, but I am sure that this gallery will be a lasting tribute to this world-changing architect and provide inspiration for our millions of visitors for many years to come.’

From a beautiful 17th century Islamic astrolabe that uses ancient mathematical techniques to map the night sky, to an early example of the famous Enigma machine, designed to resist even the most advanced mathematical techniques for code breaking during the Second World War, each historic object within the gallery has an important story to tell. Archive photography and film helps to capture these stories, and introduces the wide range of people who made, used or were impacted by each mathematical device or idea.

Some instruments and objects within the gallery clearly reference their mathematical origin. Others may surprise visitors and appear rooted in other disciplines, from classical architecture to furniture design. Visitors will see a box of glass eyes used by Francis Galton in his 1884 Anthropometric Laboratory to help measure the physical characteristics of the British public and develop statistics to support a wider social and political movement he termed ‘eugenics’. On the other side of the gallery is the pioneering Wisard pattern-recognition machine built in 1981 to attempt to re-create the ‘neural networks’ of the brain. This early Artificial Intelligence machine worked, until 1995, on a variety of projects, from banknote recognition to voice analysis, and from foetal growth monitoring in hospitals to covert surveillance for the Home Office.

A richly illustrated book has been published by Scala to accompany the new gallery. Mathematics: How it Shaped Our World, written by David Rooney, expands on the themes and stories that are celebrated in the gallery itself and includes a series of newly commissioned essays written by world-leading experts in the history and modern practice of mathematics.

David Harding, Principal Funder of the gallery and Founder and CEO of Winton said, ‘Mathematics, whilst difficult for many, is incredibly useful. To those with an aptitude for it, it is also beautiful. I’m delighted that this gallery will be both useful and beautiful.’

Mathematics: The Winton Gallery is free to visit and open daily from 8 December 2016. The gallery has been made possible through an unprecedented donation from long-standing supporters of science, David and Claudia Harding. It has also received generous support from Samsung as Principal Sponsor, MathWorks as Major Sponsor, with additional support from Adrian and Jacqui Beecroft, Iain and Jane Bratchie, the Keniston-Cooper Charitable Trust, Dr Martin Schoernig, Steve Mobbs and Pauline Thomas.

After the press release, there is the most extensive list of ‘Abouts’ I’ve seen yet (Note: This includes links to the Science Museum and other agencies),

About the Science Museum

The Science Museum’s world-class collection forms an enduring record of scientific, technological and medical achievements from across the globe. Welcoming over 3 million visitors a year, the Museum aims to make sense of the science that shapes our lives, inspiring visitors with iconic objects, award-winning exhibitions and incredible stories of scientific achievement. More information can be found at sciencemuseum.org.ukAbout Curator David Rooney

Mathematics: The Winton Gallery has been curated by Dr David Rooney, who was responsible for the award-winning 2012 Science Museum exhibition Codebreaker: Alan Turing’s Life and Legacy as well as developing galleries on time and navigation at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. David writes and speaks widely on the history of technology and engineering. His critically acclaimed first book, Ruth Belville: The Greenwich Time Lady, was described by Jonathan Meades as ‘an engrossing and eccentric slice of London history’, and by the Daily Telegraph as ‘a gem of a book’. He has recently authored Mathematics: How It Shaped Our World, to accompany the new mathematics gallery, and is currently writing a political history of traffic.About David and Claudia Harding

David and Claudia Harding are associated with Winton, one of the world’s leading quantitative investment management firms which David founded in 1997. Winton uses mathematical and scientific methods to devise, evaluate and execute investment ideas on behalf of clients all over the world. A British-based company, Winton and David and Claudia Harding have donated to numerous scientific and mathematical causes in the UK and internationally, including Cambridge University, the Crick Institute, the Max Planck Institute, and the Science Museum. The main themes of their philanthropy have been supporting basic scientific research and the communication of scientific ideas. David and Claudia reside in London.About Samsung’s Citizenship Programmes

Samsung is committed to help close the digital divide and skills gap in the UK. Samsung Digital Classrooms in schools, charities/non-profit organisations and cultural partners provide access to the latest technology. Samsung is also providing the training and maintenance support necessary to help make the transition and integration of the new technology as smooth as possible. Samsung also offers qualifications and training in technology for young people and teachers through its Digital Academies. These initiatives will inspire young people, staff and teachers to learn and teach in new exciting ways and to help encourage young people into careers using technology. Find out moreAbout MathWorks

MathWorks is the leading developer of mathematical computing software. MATLAB, the language of technical computing, is a programming environment for algorithm development, data analysis, visualisation, and numeric computation. Simulink is a graphical environment for simulation and Model-Based Design for multidomain dynamic and embedded systems. Engineers and scientists worldwide rely on these product families to accelerate the pace of discovery, innovation, and development in automotive, aerospace, electronics, financial services, biotech-pharmaceutical, and other industries. MATLAB and Simulink are also fundamental teaching and research tools in the world’s universities and learning institutions. Founded in 1984, MathWorks employs more than 3000 people in 15 countries, with headquarters in Natick, Massachusetts, USA. For additional information, visit mathworks.comAbout Zaha Hadid Architects

Zaha Hadid founded Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) in 1979. Each of ZHA’s projects builds on over thirty years of exploration and research in the interrelated fields of urbanism, architecture and design. Hadid’s pioneering vision redefined architecture for the 21st century and captured imaginations across the globe. Her legacy is embedded within the DNA of the design studio she created as ZHA’s projects combine the unwavering belief in the power of invention with concepts of connectivity and fluidity.ZHA is currently working on a diversity of projects worldwide including the new Beijing Airport Terminal Building in Daxing, China, the Sleuk Rith Institute in Phnom Penh, Cambodia and 520 West 28th Street in New York City, USA. The practice’s portfolio includes cultural, academic, sporting, residential, and transportation projects across six continents.

About Discover South Kensington

Discover South Kensington brings together the Science Museum and other leading cultural and educational organisations to promote innovation and learning. South Kensington is the home of science, arts and inspiration. Discovery is at the core of what happens here and there is so much to explore every day. discoversouthken.comAbout Zaha Hadid: Early Paintings and Drawings at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery

This week an exhibition of paintings and drawings by Zaha Hadid will open at the Serpentine Galleries that will reveal her as an artist with drawing at the very heart of her work. It will include calligraphic drawings and rarely seen private notebooks, showing her complex thoughts about architecture’s forms and relationship to the world we live in. Zaha Hadid: Early Paintings and Drawings at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery is free to visit and runs from 8th December 2016 – 12th February 2017.

I found the mentions of Zaha Hadid fascinating and so I looked her up on Wikipedia, where I found this (Note: Links have been removed),

Dame Zaha Mohammad Hadid, DBE (Arabic: زها حديد Zahā Ḥadīd; 31 October 1950 – 31 March 2016) was an Iraqi-born British architect. She was the first woman to receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize, in 2004.[1] She received the UK’s most prestigious architectural award, the Stirling Prize, in 2010 and 2011. In 2012, she was made a Dame by Elizabeth II for services to architecture, and in 2015 she became the first woman to be awarded the Royal Gold Medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects.[2]

She was dubbed by The Guardian as the ‘Queen of the curve’.[3] She liberated architectural geometry[4] with the creation of highly expressive, sweeping fluid forms of multiple perspective points and fragmented geometry that evoke the chaos and flux of modern life.[5] A pioneer of parametricism, and an icon of neo-futurism, with a formidable personality, her acclaimed work and ground-breaking forms include the aquatic centre for the London 2012 Olympics, the Broad Art Museum in the US, and the Guangzhou Opera House in China.[6] At the time of her death in 2016, Zaha Hadid Architects in London was the fastest growing British architectural firm.[7] Many of her designs are to be released posthumously, ranging in variation from the 2017 Brit Awards statuette to a 2022 FIFA World Cup stadium.[8][9]

…

Dubbed ‘Queen of the curve’, Hadid has a reputation as the world’s top female architect,[3][62][63][64][65] although her reputation is not without criticism. She is considered an architect of unconventional thinking, whose buildings are organic, dynamic and sculptural.[66][67] Stanton and others also compliment her on her unique organic designs: “One of the main characteristics of her work is that however clearly recognizable, it can never be pigeonholed into a stylistic signature. Digital knowledge, technology-driven mutations, shapes inspired by the organic and biological world, as well as geometrical interpretation of the landscape are constant elements of her practice. Yet, the multiplicity and variety of the combination among these facets prevent the risk of self-referential solutions and repetitions.”[68] Allison Lee Palmer considers Hadid a leader of Deconstructivism in architecture, writing that, “Almost all of Hadid’s buildings appear to melt, bend, and curve into a new architectural language that defies description. Her completed buildings span the globe and include the Jockey Club Innovation Tower on the north side of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University in Hong Kong, completed in 2013, that provides Hong Kong an entry into the world stage of cutting-edge architecture by revealing a design that dissolved traditional architecture, the so called modernist “glass box,” into a shattering of windows and melting of walls to form organic structures with halls and stairways that flow through the building, pooling open into rooms and foyers.”[69]

Hadid’s architectural language has been described by some as “famously extravagant” with many of her projects sponsored by “dictator states”. [emphasis mine] [70] Rowan Moore described Hadid’s Heydar Aliyev Center as “not so different from the colossal cultural palaces long beloved of Soviet and similar regimes”. Architect Sean Griffiths characterised Hadid’s work as “an empty vessel that sucks in whatever ideology might be in proximity to it”.[71] Art historian Maike Aden criticises in particular the foreclosure of Zaha Hadid’s architecture of the MAXXI in Rome towards the public and the urban life that undermines even the most impressive program to open the museum.[72]

If you think about it, most of the world’s great monuments were built by dictators or omnipotent rulers of one country or another. Getting the money and commitment can present an ethical/moral issue for any artist or architect who has a ‘grand design’.