Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised electoral reform before he and his party won the 2015 Canadian federal election. In February 2017, Trudeau’s government abandoned any and all attempts at electoral reform (see Feb. 1, 2017 article by Laura Stone about the ‘broken’ promise for the Globe and Mail). Months later, the issue lingers on.

Anyone who places the cross for a candidate in a democratic election assumes the same influence as all other voters. Therefore, as far as the population is concerned, the constituencies should be as equal as possible. (Photo: Fotolia / Stockfotos-MG)

While this research doesn’t address the issue of how to change the system so that votes might be more meaningful especially in districts where the outcome of any election is all but guaranteed, it does suggest there are better ways of changing the electoral map (redistricting), from a June 12, 2017 Technical University of Munich (TUM) press release (also on EurekAlert but dated June 23, 2017),

For democratic elections to be fair, voting districts must have similar sizes. When populations shift, districts need to be redistributed – a complex and, in many countries, controversial task when political parties attempt to influence redistricting. Mathematicians at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have now developed a method that allows the efficient calculation of optimally sized voting districts.

When constituents cast their vote for a candidate, they assume it carries the same weight as that of the others. Voting districts should thus be sized equally according to population. When populations change, boundaries need to be redrawn.

For example, 34 political districts were redrawn for the upcoming parliamentary election in Germany – a complex task. In other countries, this process often results in major controversy. Political parties often engage in gerrymandering, to create districts with a disproportionately large number of own constituents. In the United States, for example, state governments frequently exert questionable influence when redrawing the boundaries of congressional districts.

“An effective and neutral method for political district zoning, which sounds like an administrative problem, is actually of great significance from the perspective of democratic theory,” emphasizes Stefan Wurster, Professor of Policy Analysis at the Bavarian School of Public Policy at TUM. “The acceptance of democratic elections is in danger whenever parties or individuals gain an advantage out of the gate. The problem becomes particularly relevant when the allocation of parliamentary seats is determined by the number of direct mandates won. This is the case in majority election systems like in USA, Great Britain and France.”

Test case: German parliamentary electionProf. Peter Gritzmann, head of the Chair of Applied Geometry and Discrete Mathematics at TUM, in collaboration with his staff member Fabian Klemm and his colleague Andreas Brieden, professor of statistics at the University of the German Federal Armed Forces, has developed a methodology that allows the optimal distribution of electoral district boundaries to be calculated in an efficient and, of course, politically neutral manner.

The mathematicians tested their methodology using electoral districts of the German parliament. According to the German Federal Electoral Act, the number of constituents in a district should not deviate more than 15 percent from the average. In cases where the deviation exceeds 25 percent, electoral district borders must be redrawn. In this case, the relevant election commission must adhere to various provisions: For example, districts must be contiguous and not cross state, county or municipal boundaries. The electoral districts are subdivided into precincts with one polling station each.

Better than required by law“There are more ways to consolidate communities to electoral districts than there are atoms in the known universe,” says Peter Gritzmann. “But, using our model, we can still find efficient solutions in which all districts have roughly equal numbers of constituents – and that in a ‘minimally invasive’ manner that requires no voter to switch precincts.”

Deviations of 0.3 to 8.7 percent from the average size of electoral districts cannot be avoided based solely on the different number of voters in individual states. But the new methodology achieves this optimum. “Our process comes close to the theoretical limit in every state, and we end up far below the 15 percent deviation allowed by law,” says Gritzmann.

Deployment possible in many countriesThe researchers used a mathematical model developed in the working group to calculate the electoral districts: “Geometric clustering” groups the communities to clusters, the optimized electoral districts. The target definition for calculations can be arbitrarily modified, making the methodology applicable to many countries with different election laws.

The methodology is also applicable to other types of problems: for example, in voluntary lease and utilization exchanges in agriculture, to determine adequate tariff groups for insurers or to model hybrid materials. “However, drawing electoral district boundaries is a very special application, because here mathematics can help strengthen democracies,” sums up Gritzmann.

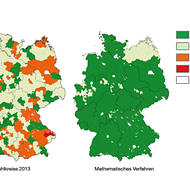

Although the electoral wards for the German election were newly tailored in 2012, already in 2013, the year of the election, population changes led to deviations above the desired maximum value in some of them (left). The mathematical method results in significantly lower deviations, thus providing better fault tolerance. (Image: F. Klemm / TUM)

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Constrained clustering via diagrams: A unified theory and its application to electoral district design by Andreas Brieden, Peter Gritzmann, Fabian Klemma. European Journal of Operational Research Volume 263, Issue 1, 16 November 2017, Pages 18–34 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2017.04.018

This paper is behind a paywall.

While the redesign of electoral districts has been a contentious issue federally and provincially in Canada (and I imagine in municipalities where this is representation by districts), the focus for electoral reform had been on eliminating the ‘first-past-the-post’ system and replacing it with something new. Apparently, there is also some interest in the US. A June 27, 2017 article by David Daley for salon.com describes one such initiative,

…

Some people blame gerrymandering, while others cite geography or rage against dark money. All are corrupting factors. All act as accelerants on the underlying issue: Our winner-take-all [first-ast-the-post]system of districting that gives all the seats to the side with 50 percent plus one vote and no representation to the other 49.9 percent. We could end gerrymandering tomorrow and it wouldn’t help the unrepresented Republicans in Connecticut, or Democrats in Kansas, feel like they had a voice in Congress.

A Virginia congressman wants to change this. Rep. Don Beyer, a Democrat, introduced something called the Fair Representation Act this week. Beyer aims to wipe out today’s map of safe red and blue seats and replace them with larger, multimember districts (drawn by nonpartisan commissions) of three, four or five representatives. Smaller states would elect all members at large. All members would then be elected with ranked-choice voting. That would ensure that as many voters as possible elect a candidate of their choice: In a multimember district with five seats, for example, a candidate could potentially win with one-sixth of the vote.

This is how you fix democracy. The larger districts would help slay the gerrymander. A ranked-choice system would eliminate our zero-sum, winner-take-all politics. Leadership of the House would belong to the side with the most votes — unlike in 2012, for example, when Democratic House candidates received 1.4 million more votes than Republicans, but the GOP maintained a 33-seat majority. No wasted votes and no spoilers, bridge builders in Congress, and (at least in theory) less negative campaigning as politicians vied to be someone’s second choice if not their first. There’s a lot to like here.

There are other similar schemes but the idea is always to reestablish the primacy (meaningfulness) of a vote and to achieve better representation of the country’s voters and interests. As for the failed Canadian effort, such as it was, the issue’s failure to fade away hints that Canadian politicians at whatever jurisdictional level they inhabit might want to tackle the situation a little more seriously than they have previously.