There’s a possibility that metal-organic frameworks could be used to clean up nuclear waste according to an Aug. 5, 2015 news item on phys.org,

One of the most versatile and widely applicable classes of materials being studied today are the metal-organic frameworks. These materials, known as MOFs, are characterized by metal ions or metal-ion clusters that are linked together with organic molecules, forming ordered crystal structures that contain tiny cage-like pores with diameters of two nanometers or less.

MOFs can be thought of as highly specialized and customizable sieves. By designing them with pores of a certain size, shape, and chemical composition, researchers can tailor them for specific purposes. A few of the many, many possible applications for MOFs are storing hydrogen in fuel cells, capturing environmental contaminants, or temporarily housing catalytic agents for chemical reactions.

At [US Department of Energy] Brookhaven National Laboratory, physicist Sanjit Ghose and his collaborators have been studying MOFs designed for use in the separation of waste from nuclear reactors, which results from the reprocessing of nuclear fuel rods. He is targeting two waste products in particular: the noble gases xenon (Xe) and krypton (Kr).

An Aug. 4, 2015 Brookhaven National Laboratory news release, which originated the news item, describes not only the research and the reasons for it but also the institutional collaborations necessary to conduct the research,

There are compelling economic and environmental reasons to separate Xe and Kr from the nuclear waste stream. For one, because they have very different half-lives – about 36 days for Xe and nearly 11 years for Kr – pulling out the Xe greatly reduces the amount of waste that needs to be stored long-term before it is safe to handle. Additionally, the extracted Xe can be used for industrial applications, such as in commercial lighting and as an anesthetic. This research may also help scientists determine how to create MOFs that can remove other materials from the nuclear waste stream and expose the remaining unreacted nuclear fuel for further re-use. This could lead to much less overall waste that must be stored long-term and a more efficient system for producing nuclear energy, which is the source of about 20 percent of the electricity in the U.S.

Because Xe and Kr are noble gases, meaning their outer electron orbitals are filled and they don’t tend to bind to other atoms, they are difficult to manipulate. The current method for extracting them from the nuclear waste stream is cryogenic distillation, a process that is energy-intensive and expensive. The MOFs studied here use a very different approach: polarizing the gas atoms dynamically, just enough to draw them in using the van der Waals force. The mechanism works at room temperature, but also at hotter temperatures, which is key if the MOFs are to be used in a nuclear environment.

Recently, Ghose co-authored two papers that describe MOFs capable of adsorbing Xe and Kr, and excel at separating the Xe from the Kr. The papers are published in the May 22 online edition of the Journal of the American Chemical Society and the April 16 online edition of the Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters.

“Only a handful of noble-gas-specific MOFs have been studied so far, and we felt there was certainly scope for improvement through the discovery of more selective materials,” said Ghose.

Both MOF studies were carried out by large multi-institution collaborations, using a combination of X-ray diffraction, theoretical modeling, and other methods. The X-ray work was performed at Brookhaven’s former National Synchrotron Light Source (permanently closed and replaced by its successor, NSLS-II) and the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory (ANL), both DOE Office of Science User Facilities.

The JACS paper was co-authored by researchers from Brookhaven Lab, Stony Brook University (SBU), Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), and the University of Amsterdam. Authors on the JPCL paper include scientists from Brookhaven, SBU, PNNL, ANL, the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY) in Germany, and DM Strachan, LLC.

Here’s more about the first published paper in the Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters (JCPL) (from the news release)

A nickel-based MOF

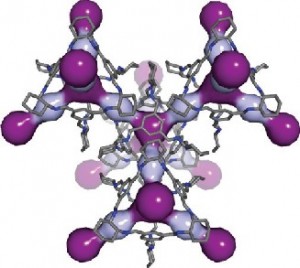

The MOF studied in the JCPL paper consists of nickel (Ni) and the organic compound dioxido-benzene-dicarboxylate (DOBC), and is thus referred to as Ni-DOBDC. Ni-DOBDC can adsorb both Xe and Kr at room temperature but is highly selective toward Xe. In fact, it boasts what may be the highest Xe adsorption capacity of a MOF discovered to date.

The group studied Ni-DOBC using two main techniques: X-ray diffraction and first-principles density functional theory (DFT). The paper is the first published report to detail the adsorption mechanism by which the MOF takes in these noble gases at room temperature and pressure.

“Our results provide a fundamental understanding of the adsorption structure and the interactions between the MOF and the gas by combining direct structural analyses from experimental X-ray diffraction data and DFT calculations,” said Ghose.

The group was also able to discover the existence of a secondary site at the pore center in addition to the six-fold primary site. The seven-atom loading scheme was initially proposed by theorist Yan Li, an co-author of the JCPL paper and formerly on staff at Brookhaven (she is now an editor at Physical Review B), which was confirmed experimentally and theoretically. Data also indicate that Xe are adsorbed more strongly than Kr, due to its higher atomic polarizability. They also discovered a temperature-dependence of the adsorption that furthers this MOF’s selectivity for Xe over Kr. As the temperature was increased above room temperature, the Kr adsorption drops more drastically than for Xe. Over the entire temperature range tested, Xe adsorption always dominates that of Kr.

“The high separation capacity of Ni-DOBDC suggests that it has great potential for removing Xe from Kr in the off-gas streams in nuclear spent fuel reprocessing, as well as filtering Xe at low concentration from other gas mixtures,” said Ghose.

Ghose and Li are now preparing a manuscript that will discuss a more in-depth investigation into the possibility of packing in even more Xe atoms.

“Because of the confinement offered by each pore, we want to see if it’s possible to fit enough Xe in each chamber to form a solid,” said Li.

Ghose and Li hope to experimentally test this idea at NSLS-II in the future, at the facility’s X-ray Powder Diffraction (XPD) beamline, which Ghose has helped develop and build. Additional future studies of these and other MOFs will also take place at XPD. For example, they want to see what happens when other gases are present, such as nitrogen oxides, to mimic what happens in an actual nuclear reactor.

Then, there was the second paper published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS),

Another MOF, Another Promising Result

In the JACS paper, Ghose and researchers from Brookhaven, SBU, PNNL, and the University of Amsterdam describe a second MOF, dubbed Stony Brook MOF-2 (SBMOF-2). It also captures both Xe and Kr at room temperature and pressure, although is about ten times as effective at taking in Xe, with Xe taking up as much as 27 percent of its weight. SBMOF-2 had been theoretically predicted to be an efficient adsorbent for Xe and Kr, but until this research there had been no experimental results to back up the prediction.

“Our study is different than MOF research done by other groups,” said chemist John Parise, a coauthor of the JACS paper who holds a joint position with Brookhaven and SBU. “We did a lot of testing and investigated the capture mechanism very closely to get clues that would help us understand why the MOF worked, and how to tailor the structure to have even better properties.”

SBMOF-2 contains calcium (Ca) ions and an organic compound with the chemical formula C34H22O8. X-ray data show that its structure is unusual among microporous MOFs. It has fewer calcium sites than expected and an excess of oxygen over calcium. The calcium and oxgyen form CaO6, which takes the form of a three-dimensional octahedron. Notably, none of the six oxygen atoms bound to the calcium ion are shared with any other nearby calcium ions. The authors believe that SBMOF-2 is the first microporous MOF with these isolated CaO6 octahedra, which are connected by organic linker molecules.

The group discovered that the preference of SBMOF-2 for Xe over Kr is due to both the geometry and chemistry of its pores. All the pores have diamond-shaped cross sections, but they come in two sizes, designated type-1 and type-2. Both sizes are a better fit for the Xe molecule. The interiors of the pores have walls made of phenyl groups – ring-shaped C6H5 molecules – along with delocalized electron clouds and H atoms pointing into the pore. The type-2 pores also have hydroxyl anions (OH-) available. All of these features provide are potential sites for adsorbed Xe and Kr atoms.

In follow-up studies, Ghose and his colleagues will use these results to guide them as they determine what changes can be made to these MOFs to improve adsorption, as well as to determine what existing MOFs may yield similar or better performance.

Here are links to and citations for both papers,

Understanding the Adsorption Mechanism of Xe and Kr in a Metal–Organic Framework from X-ray Structural Analysis and First-Principles Calculations by Sanjit K. Ghose, Yan Li, Andrey Yakovenko, Eric Dooryhee, Lars Ehm, Lynne E. Ecker, Ann-Christin Dippel, Gregory J. Halder, Denis M. Strachan, and Praveen K. Thallapally. J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2015, 6 (10), pp 1790–1794 DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b00440 Publication Date (Web): April 16, 2015

Copyright © 2015 American Chemical Society

Direct Observation of Xe and Kr Adsorption in a Xe-Selective Microporous Metal–Organic Framework by Xianyin Chen, Anna M. Plonka, Debasis Banerjee, Rajamani Krishna, Herbert T. Schaef, Sanjit Ghose, Praveen K. Thallapally, and John B. Parise. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2015, 137 (22), pp 7007–7010 DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5b02556 Publication Date (Web): May 22, 2015

Copyright © 2015 American Chemical Society

Both papers are behind a paywall.