Patricia Piccinini’s Curious Imaginings Courtesy: Vancouver Biennale [downloaded from http://dailyhive.com/vancouver/vancouver-biennale-unsual-public-art-2018/]

While this posting is mostly about the Biennale and Piccinini’s work, there is a ‘science’ subsection featuring the science of CRISPR and xenotransplantation. Getting back to the Biennale and Piccinini: A major public art event since 1988, the Vancouver Biennale has hosted over 91 outdoor sculptures and new media works by more than 78 participating artists from over 25 countries and from 4 continents.

Quickie description of the 2018 – 2020 Vancouver Biennale

The latest edition of the Vancouver Biennale was featured in a June 6, 2018 news item on the Daily Hive (Vancouver),

The Vancouver Biennale will be bringing new —and unusual— works of public art to the city beginning this June.

The theme for this season’s Vancouver Biennale exhibition is “re-IMAGE-n” and it kicks off on June 20 [2018] in Vanier Park with Saudi artist Ajlan Gharem’s Paradise Has Many Gates.

Gharem’s architectural chain-link sculpture resembles a traditional mosque, the piece is meant to challenge the notions of religious orthodoxy and encourages individuals to image a space free of Islamophobia.

…

Melbourne artist Patricia Piccinini’s Curious Imaginings is expected to be one of the most talked about installations of the exhibit. Her style of “oddly captivating, somewhat grotesque, human-animal hybrid creature” is meant to be shocking and thought-provoking.

Piccinini’s interactive [emphasis mine] experience will “challenge us to explore the social impacts of emerging biotechnology and our ethical limits in an age where genetic engineering and digital technologies are already pushing the boundaries of humanity.”

Piccinini’s work will be displayed in the 105-year-old Patricia Hotel in Vancouver’s Strathcona neighbourhood. The 90-day ticketed exhibition [emphasis mine] is scheduled to open this September [2018].

…

Given that this blog is focused on nanotechnology and other emerging technologies such as CRISPR, I’m focusing on Piccinini’s work and its art/science or sci-art status. This image from the GOMA Gallery where Piccinini’s ‘Curious Affection‘ installation is being shown from March 24 – Aug. 5, 2018 in Brisbane, Queensland, Australia may give you some sense of what one of her installations is like,

Courtesy: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA)

I spoke with Serena at the Vancouver Biennale office and asked about the ‘interactive’ aspect of Piccinini’s installation. She suggested the term ‘immersive’ as an alternative. In other words, you won’t be playing with the sculptures or pressing buttons and interacting with computer screens or robots. She also noted that the ticket prices have not been set yet and they are currently developing events focused on the issues raised by the installation. She knew that 2018 is the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein but I’m not sure how the Biennale folks plan (or don’t plan) to integrate any recognition of the novle’s impact on the discussions about ‘new’ technologies .They expect Piccinini will visit Vancouver. (Note 1: Piccinini’s work can also be seen in a group exhibition titled: Frankenstein’s Birthday Party at the Hosfselt Gallery in San Francisco (California, US) from June 23 – August 11, 2018. Note 2: I featured a number of international events commemorating the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein, in my Feb. 26, 2018 posting. Note 3: The term ‘Frankenfoods’ helped to shape the discussion of genetically modified organisms and food supply on this planet. It was a wildly successful campaign for activists affecting legislation in some areas of research. Scientists have not been as enthusiastic about the effects. My January 15, 2009 posting briefly traces a history of the term.)

The 2018 – 2020 Vancouver Biennale and science

A June 7, 2018 Vancouver Biennale news release provides more detail about the current series of exhibitions,

The Biennale is also committed to presenting artwork at the cutting edge of discussion and in keeping with the STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, math[ematics]) approach to integrating the arts and sciences. In August [2018], Colombian/American visual artist Jessica Angel will present her monumental installation Dogethereum Bridge at Hinge Park in Olympic Village. Inspired by blockchain technology, the artwork’s design was created through the integration of scientific algorithms, new developments in technology, and the arts. This installation, which will serve as an immersive space and collaborative hub for artists and technologists, will host a series of activations with blockchain as the inspirational jumping-off point.

…

In what is expected to become one of North America’s most talked-about exhibitions of the year, Melbourne artist Patricia Piccinini’s Curious Imaginings will see the intersection of art, science, and ethics. For the first time in the Biennale’s fifteen years of creating transformative experiences, and in keeping with the 2018-2020 theme of “re-IMAGE-n,” the Biennale will explore art in unexpected places by exhibiting in unconventional interior spaces. The hyperrealist “world of oddly captivating, somewhat grotesque, human-animal hybrid creatures” will be the artist’s first exhibit in a non-museum setting, transforming a wing of the 105-year-old Patricia Hotel. Situated in Vancouver’s oldest neighbourbood of Strathcona, Piccinini’s interactive experience will “challenge us to explore the social impacts of emerging bio-technology and our ethical limits in an age where genetic engineering and digital technologies are already pushing the boundaries of humanity.” In this intimate hotel setting located in a neighborhood continually undergoing its own change, Curious Imaginings will empower visitors to personally consider questions posed by the exhibition, including the promises and consequences of genetic research and human interference. …

There are other pieces being presented at the Biennale but my special interest is in the art/sci pieces and, at this point, CRISPR.

Piccinini in more depth

You can find out more about Patricia Piccinini in her biography on the Vancouver Biennale website but I found this Char Larsson April 7, 2018 article for the Independent (UK) more informative (Note: A link has been removed),

Patricia Piccinini’s sculptures are deeply disquieting. Walking through Curious Affection, her new solo exhibition at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art, is akin to entering a science laboratory full of DNA experiments. Made from silicone, fibreglass and even human hair, her sculptures are breathtakingly lifelike, however, we can’t be sure what life they are like. The artist creates an exuberant parallel universe where transgenic experiments flourish and human evolution has given way to genetic engineering and DNA splicing.

Curious Affection is a timely and welcome recognition of Piccinini’s enormous contribution to reaching back to the mid-1990s. Working across a variety of mediums including photography, video and drawing, she is perhaps best known for her hyperreal creations.

As a genre, hyperrealism depends on the skill of the artist to create the illusion of reality. To be truly successful, it must convince the spectator of its realness. Piccinini acknowledges this demand, but with a delightful twist. The excruciating attention to detail deliberately solicits our desire to look, only to generate unease, as her sculptures are imbued with a fascinating otherness. Part human, part animal, the works are uncannily familiar, but also alarmingly “other”.

…

Inspired by advances in genetically modified pigs to generate replacement organs for humans [also known as xenotransplantation], we are reminded that Piccinini has always been at the forefront of debates concerning the possibilities of science, technology and DNA cloning. She does so, however, with a warm affection and sense of humour, eschewing the hysterical anxiety frequently accompanying these scientific developments.

Beyond the astonishing level of detail achieved by working with silicon and fibreglass, there is an ethics at work here. Piccinini is asking us not to avert our gaze from the other, and in doing so, to develop empathy and understanding through the encounter.

I encourage anyone who’s interested to read Larsson’s entire piece (April 7, 2018 article).

According to her Wikipedia entry, Piccinini works in a variety of media including video, sound, sculpture, and more. She also has her own website.

Gene editing and xenotransplantation

Sarah Zhang’s June 8, 2018 article for The Atlantic provides a peek at the extraordinary degree of interest and competition in the field of gene editing and CRISPR ((clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats))/Cas9 research (Note: A link has been removed),

China Is Genetically Engineering Monkeys With Brain Disorders

Guoping Feng applied to college the first year that Chinese universities reopened after the Cultural Revolution. It was 1977, and more than a decade’s worth of students—5.7 million—sat for the entrance exams. Feng was the only one in his high school to get in. He was assigned—by chance, essentially—to medical school. Like most of his contemporaries with scientific ambitions, he soon set his sights on graduate studies in the United States. “China was really like 30 to 50 years behind,” he says. “There was no way to do cutting-edge research.” So in 1989, he left for Buffalo, New York, where for the first time he saw snow piled several feet high. He completed his Ph.D. in genetics at the State University of New York at Buffalo.

Feng is short and slim, with a monk-like placidity and a quick smile, and he now holds an endowed chair in neuroscience at MIT, where he focuses on the genetics of brain disorders. His 45-person lab is part of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, which was established in 2000 with the promise of a $350 million donation, the largest ever received by the university. In short, his lab does not lack for much.

Yet Feng now travels to China several times a year, because there, he can pursue research he has not yet been able to carry out in the United States. [emphasis mine] …

…

Feng had organized a symposium at SIAT [Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology], and he was not the only scientist who traveled all the way from the United States to attend: He invited several colleagues as symposium speakers, including a fellow MIT neuroscientist interested in tree shrews, a tiny mammal related to primates and native to southern China, and Chinese-born neuroscientists who study addiction at the University of Pittsburgh and SUNY Upstate Medical University. Like Feng, they had left China in the ’80s and ’90s, part of a wave of young scientists in search of better opportunities abroad. Also like Feng, they were back in China to pursue a type of cutting-edge research too expensive and too impractical—and maybe too ethically sensitive—in the United States.

Here’s what precipitated Feng’s work in China, (from Zhang’s article; Note: Links have been removed)

At MIT, Feng’s lab worked on genetically engineering a monkey species called marmosets, which are very small and genuinely bizarre-looking. They are cheaper to keep due to their size, but they are a relatively new lab animal, and they can be difficult to train on lab tasks. For this reason, Feng also wanted to study Shank3 on macaques in China. Scientists have been cataloging the social behavior of macaques for decades, making it an obvious model for studies of disorders like autism that have a strong social component. Macaques are also more closely related to humans than marmosets, making their brains a better stand-in for those of humans.

The process of genetically engineering a macaque is not trivial, even with the advanced tools of CRISPR. Researchers begin by dosing female monkeys with the same hormones used in human in vitro fertilization. They then collect and fertilize the eggs, and inject the resulting embryos with CRISPR proteins using a long, thin glass needle. Monkey embryos are far more sensitive than mice embryos, and can be affected by small changes in the pH of the injection or the concentration of CRISPR proteins. Only some of the embryos will have the desired mutation, and only some will survive once implanted in surrogate mothers. It takes dozens of eggs to get to just one live monkey, so making even a few knockout monkeys required the support of a large breeding colony.

The first Shank3 macaque was born in 2015. Four more soon followed, bringing the total to five.

To visit his research animals, Feng now has to fly 8,000 miles across 12 time zones. It would be a lot more convenient to carry out his macaque research in the United States, of course, but so far, he has not been able to.

He originally inquired about making Shank3 macaques at the New England Primate Research Center, one of eight national primate research centers then funded by the National Institutes of Health in partnership with a local institution (Harvard Medical School, in this case). The center was conveniently located in Southborough, Massachusetts, just 20 miles west of the MIT campus. But in 2013, Harvard decided to shutter the center.

The decision came as a shock to the research community, and it was widely interpreted as a sign of waning interest in primate research in the United States. While the national primate centers have been important hubs of research on HIV, Zika, Ebola, and other diseases, they have also come under intense public scrutiny. Animal-rights groups like the Humane Society of the United States have sent investigators to work undercover in the labs, and the media has reported on monkey deaths in grisly detail. Harvard officially made its decision to close for “financial” reasons. But the announcement also came after the high-profile deaths of four monkeys from improper handling between 2010 and 2012. The deaths sparked a backlash; demonstrators showed up at the gates. The university gave itself two years to wind down their primate work, officially closing the center in 2015.

“They screwed themselves,” Michael Halassa, the MIT neuroscientist who spoke at Feng’s symposium, told me in Shenzhen. Wei-Dong Yao, another one of the speakers, chimed in, noting that just two years later CRISPR has created a new wave of interest in primate research. Yao was one of the researchers at Harvard’s primate center before it closed; he now runs a lab at SUNY Upstate Medical University that uses genetically engineered mouse and human stem cells, and he had come to Shenzhen to talk about restarting his addiction research on primates.

Here’s comes the competition (from Zhang’s article; Note: Links have been removed),

While the U.S. government’s biomedical research budget has been largely flat, both national and local governments in China are eager to raise their international scientific profiles, and they are shoveling money into research. A long-rumored, government-sponsored China Brain Project is supposed to give neuroscience research, and primate models in particular, a big funding boost. Chinese scientists may command larger salaries, too: Thanks to funding from the Shenzhen local government, a new principal investigator returning from overseas can get 3 million yuan—almost half a million U.S. dollars—over his or her first five years. China is even finding success in attracting foreign researchers from top U.S. institutions like Yale.

…

In the past few years, China has seen a miniature explosion of genetic engineering in monkeys. In Kunming, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, scientists have created monkeys engineered to show signs of Parkinson’s, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, autism, and more. And Feng’s group is not even the only one in China to have created Shank3 monkeys. Another group—a collaboration primarily between researchers at Emory University and scientists in China—has done the same.

…

Chinese scientists’ enthusiasm for CRISPR also extends to studies of humans, which are moving much more quickly, and in some cases under less oversight, than in the West. The first studies to edit human embryos and first clinical trials for cancer therapies using CRISPR have all happened in China. [emphases mine]

Some ethical issues are also covered (from Zhang’s article),

Parents with severely epileptic children had asked him if it would be possible to study the condition in a monkey. Feng told them what he thought would be technically possible. “But I also said, ‘I’m not sure I want to generate a model like this,’” he recalled. Maybe if there were a drug to control the monkeys’ seizures, he said: “I cannot see them seizure all the time.”

But is it ethical, he continued, to let these babies die without doing anything? Is it ethical to generate thousands or millions of mutant mice for studies of brain disorders, even when you know they will not elucidate much about human conditions?

Primates should only be used if other models do not work, says Feng, and only if a clear path forward is identified. The first step in his work, he says, is to use the Shank3 monkeys to identify the changes the mutations cause in the brain. Then, researchers might use that information to find targets for drugs, which could be tested in the same monkeys. He’s talking with the Oregon National Primate Research Center about carrying out similar work in the United States. ….[Note: I have a three-part series about CRISPR and germline editing* in the US, precipitated by research coming out of Oregon, Part 1, which links to the other parts, is here.]

Zhang’s June 8, 2018 article is excellent and I highly recommend reading it.

I touched on the topic of xenotransplanttaion in a commentary on a book about the science of the television series, Orphan Black in a January 31,2018 posting (Note: A chimera is what you use to incubate a ‘human’ organ for transplantation or, more accurately, xenotransplantation),

On the subject of chimeras, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) featured a January 26, 2017 article about the pig-human chimeras on its website along with a video,

The end

I am very excited to see Piccinini’s work come to Vancouver. There have been a number of wonderful art and art/science installations and discussions here but this is the first one (I believe) to tackle the emerging gene editing technologies and the issues they raise. (It also fits in rather nicely with the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein which continues to raise issues and stimulate discussion.)

In addition to the ethical issues raised in Zhang’s article, there are some other philosophical questions:

- what does it mean to be human

- if we are going to edit genes to create hybrid human/animals, what are they and how do they fit into our current animal/human schema

- are you still human if you’ve had an organ transplant where the organ was incubated in a pig

There are also going to be legal issues. In addition to any questions about legal status, there are also fights about intellectual property such as the one involving Harvard & MIT’s [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] Broad Institute vs the University of California at Berkeley (March 15, 2017 posting)..

While I’m thrilled about the Piccinini installation, it should be noted the issues raised by other artworks hosted in this version of the Biennale are important. Happily, they have been broached here in Vancouver before and I suspect this will result in more nuanced ‘conversations’ than are possible when a ‘new’ issue is introduced.

Bravo 2018 – 2020 Vancouver Biennale!

* Germline editing is when your gene editing will affect subsequent generations as opposed to editing out a mutated gene for the lifetime of a single individual.

Art/sci and CRISPR links

This art/science posting may prove of some interest:

The connectedness of living things: an art/sci project in Saskatchewan: evolutionary biology (February 16, 2018)

A selection of my CRISPR posts:

CRISPR and editing the germline in the US (part 1 of 3): In the beginning (August 15, 2017)

NOTE: An introductory CRISPR video describing how CRISPR/Cas9 works was embedded in part1.

Why don’t you CRISPR yourself? (January 25, 2018)

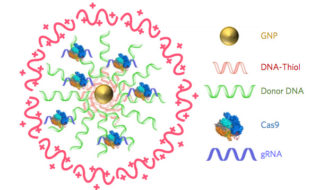

Editing the genome with CRISPR ((clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats)-carrying nanoparticles (January 26, 2018)

Immune to CRISPR? (April 10, 2018)