A December 18, 2017 news item on Nanowerk announces research that demonstrates graphene can be harder than diamonds (Note: A link has been removed),

Imagine a material as flexible and lightweight as foil that becomes stiff and hard enough to stop a bullet on impact. In a newly published paper in Nature Nanotechnology (“Ultrahard carbon film from epitaxial two-layer graphene”), researchers across The City University of New York (CUNY) describe a process for creating diamene: flexible, layered sheets of graphene that temporarily become harder than diamond and impenetrable upon impact.

Scientists at the Advanced Science Research Center (ASRC) at the Graduate Center, CUNY, worked to theorize and test how two layers of graphene — each one-atom thick — could be made to transform into a diamond-like material upon impact at room temperature. The team also found the moment of conversion resulted in a sudden reduction of electric current, suggesting diamene could have interesting electronic and spintronic properties. The new findings will likely have applications in developing wear-resistant protective coatings and ultra-light bullet-proof films.

A December 18, 2017 CUNY news release, which originated the news item, provides a little more detail,

“This is the thinnest film with the stiffness and hardness of diamond ever created,” said Elisa Riedo, professor of physics at the ASRC and the project’s lead researcher. “Previously, when we tested graphite or a single atomic layer of graphene, we would apply pressure and feel a very soft film. But when the graphite film was exactly two-layers thick, all of a sudden we realized that the material under pressure was becoming extremely hard and as stiff, or stiffer, than bulk diamond.”

Angelo Bongiorno, associate professor of chemistry at CUNY College of Staten Island and part of the research team, developed the theory for creating diamene. He and his colleagues used atomistic computer simulations to model potential outcomes when pressurizing two honeycomb layers of graphene aligned in different configurations. Riedo and other team members then used an atomic force microscope to apply localized pressure to two-layer graphene on silicon carbide substrates and found perfect agreement with the calculations. Experiments and theory both show that this graphite-diamond transition does not occur for more than two layers or for a single graphene layer.

“Graphite and diamonds are both made entirely of carbon, but the atoms are arranged differently in each material, giving them distinct properties such as hardness, flexibility and electrical conduction,” Bongiorno said. “Our new technique allows us to manipulate graphite so that it can take on the beneficial properties of a diamond under specific conditions.”

The research team’s successful work opens up possibilities for investigating graphite-to-diamond phase transition in two-dimensional materials, according to the paper. Future research could explore methods for stabilizing the transition and allow for further applications for the resulting materials.

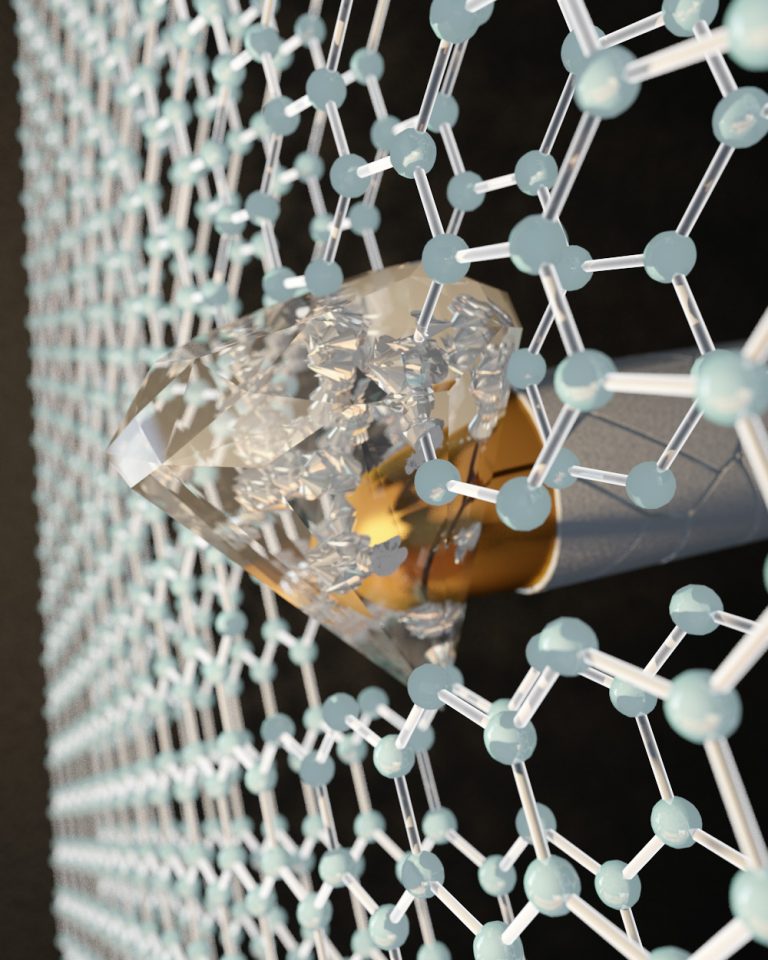

There’s an artist’s representation of a bullet’s impact on graphene,

By applying pressure at the nanoscale with an indenter to two layers of graphene, each one-atom thick, CUNY researchers transformed the honeycombed graphene into a diamond-like material at room temperature. Photo credit: Ella Maru Studio Courtesy: CUNY

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Ultrahard carbon film from epitaxial two-layer graphene by Yang Gao, Tengfei Cao, Filippo Cellini, Claire Berger, Walter A. de Heer, Erio Tosatti, Elisa Riedo, & Angelo Bongiorno. Nature Nanotechnology (2017) doi:10.1038/s41565-017-0023-9 Published online: 18 December 2017

This paper is behind a paywall.

![Nanofriction at the tip of the microscope. Courtesy SISSA [Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzat], Italy](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Nanofriction-300x153.jpg)