As scientists continue exploring the nanoscale, it seems that finding the number of atoms in your particle makes a difference is no longer so surprising. From a Jan. 28, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily,

Combining experimental investigations and theoretical simulations, researchers have explained why platinum nanoclusters of a specific size range facilitate the hydrogenation reaction used to produce ethane from ethylene. The research offers new insights into the role of cluster shapes in catalyzing reactions at the nanoscale, and could help materials scientists optimize nanocatalysts for a broad class of other reactions.

A Jan. 28, 2016 Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech) news release (*also on EurekAlert*), which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

At the macro-scale, the conversion of ethylene has long been considered among the reactions insensitive to the structure of the catalyst used. However, by examining reactions catalyzed by platinum clusters containing between 9 and 15 atoms, researchers in Germany and the United States found that at the nanoscale, that’s no longer true. The shape of nanoscale clusters, they found, can dramatically affect reaction efficiency.

While the study investigated only platinum nanoclusters and the ethylene reaction, the fundamental principles may apply to other catalysts and reactions, demonstrating how materials at the very smallest size scales can provide different properties than the same material in bulk quantities. …

“We have re-examined the validity of a very fundamental concept on a very fundamental reaction,” said Uzi Landman, a Regents’ Professor and F.E. Callaway Chair in the School of Physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “We found that in the ultra-small catalyst range, on the order of a nanometer in size, old concepts don’t hold. New types of reactivity can occur because of changes in one or two atoms of a cluster at the nanoscale.”

The widely-used conversion process actually involves two separate reactions: (1) dissociation of H2 molecules into single hydrogen atoms, and (2) their addition to the ethylene, which involves conversion of a double bond into a single bond. In addition to producing ethane, the reaction can also take an alternative route that leads to the production of ethylidyne, which poisons the catalyst and prevents further reaction.

The project began with Professor Ueli Heiz and researchers in his group at the Technical University of Munich experimentally examining reaction rates for clusters containing 9, 10, 11, 12 or 13 platinum atoms that had been placed atop a magnesium oxide substrate. The 9-atom nanoclusters failed to produce a significant reaction, while larger clusters catalyzed the ethylene hydrogenation reaction with increasingly better efficiency. The best reaction occurred with 13-atom clusters.

Bokwon Yoon, a research scientist in Georgia Tech’s Center for Computational Materials Science, and Landman, the center’s director, then used large-scale first-principles quantum mechanical simulations to understand how the size of the clusters – and their shape – affected the reactivity. Using their simulations, they discovered that the 9-atom cluster resembled a symmetrical “hut,” while the larger clusters had bulges that served to concentrate electrical charges from the substrate.

“That one atom changes the whole activity of the catalyst,” Landman said. “We found that the extra atom operates like a lightning rod. The distribution of the excess charge from the substrate helps facilitate the reaction. Platinum 9 has a compact shape that doesn’t facilitate the reaction, but adding just one atom changes everything.”

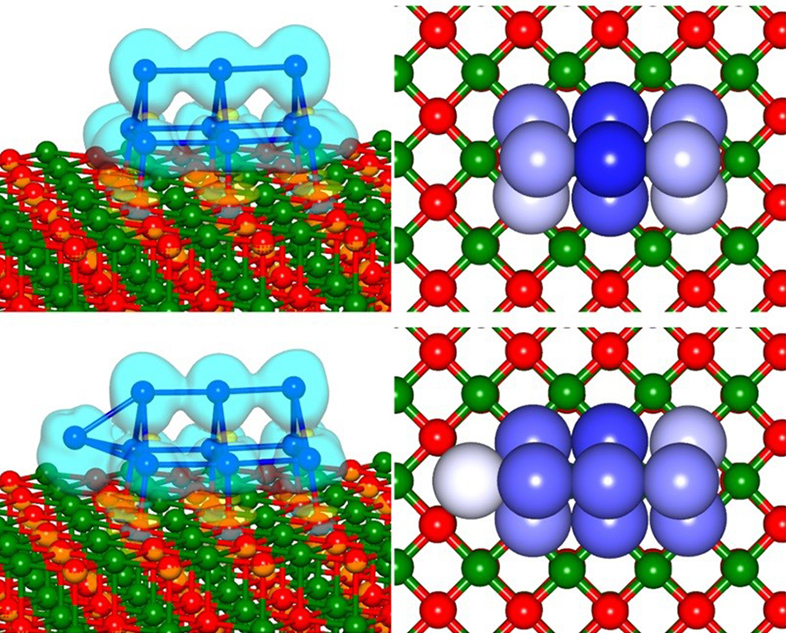

Here’s an illustration featuring the difference between a 9 atom cluster and a 10 atom cluster,

A single atom makes a difference in the catalytic properties of platinum nanoclusters. Shown are platinum 9 (top) and platinum 10 (bottom). (Credit: Uzi Landman, Georgia Tech)

The news release explains why the larger clusters function as catalysts,

Nanoclusters with 13 atoms provided the maximum reactivity because the additional atoms shift the structure in a phenomena Landman calls “fluxionality.” This structural adjustment has also been noted in earlier work of these two research groups, in studies of clusters of gold [emphasis mine] which are used in other catalytic reactions.

“Dynamic fluxionality is the ability of the cluster to distort its structure to accommodate the reactants to actually enhance reactivity,” he explained. “Only very small aggregates of metal can show such behavior, which mimics a biochemical enzyme.”

The simulations showed that catalyst poisoning also varies with cluster size – and temperature. The 10-atom clusters can be poisoned at room temperature, while the 13-atom clusters are poisoned only at higher temperatures, helping to account for their improved reactivity.

“Small really is different,” said Landman. “Once you get into this size regime, the old rules of structure sensitivity and structure insensitivity must be assessed for their continued validity. It’s not a question anymore of surface-to-volume ratio because everything is on the surface in these very small clusters.”

While the project examined only one reaction and one type of catalyst, the principles governing nanoscale catalysis – and the importance of re-examining traditional expectations – likely apply to a broad range of reactions catalyzed by nanoclusters at the smallest size scale. Such nanocatalysts are becoming more attractive as a means of conserving supplies of costly platinum.

“It’s a much richer world at the nanoscale than at the macroscopic scale,” added Landman. “These are very important messages for materials scientists and chemists who wish to design catalysts for new purposes, because the capabilities can be very different.”

Along with the experimental surface characterization and reactivity measurements, the first-principles theoretical simulations provide a unique practical means for examining these structural and electronic issues because the clusters are too small to be seen with sufficient resolution using most electron microscopy techniques or traditional crystallography.

“We have looked at how the number of atoms dictates the geometrical structure of the cluster catalysts on the surface and how this geometrical structure is associated with electronic properties that bring about chemical bonding characteristics that enhance the reactions,” Landman added.

I highlighted the news release’s reference to gold nanoclusters as I have noted the number issue in two April 14, 2015 postings, neither of which featured Georgia Tech, Gold atoms: sometimes they’re a metal and sometimes they’re a molecule and Nature’s patterns reflected in gold nanoparticles.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the ‘platinum catalyst’ paper,

Structure sensitivity in the nonscalable regime explored via catalysed ethylene hydrogenation on supported platinum nanoclusters by Andrew S. Crampton, Marian D. Rötzer, Claron J. Ridge, Florian F. Schweinberger, Ueli Heiz, Bokwon Yoon, & Uzi Landman. Nature Communications 7, Article number: 10389 doi:10.1038/ncomms10389 Published 28 January 2016

This paper is open access.

*’also on EurekAlert’ added Jan. 29, 2016.