An August 24, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily describes a ‘shapeshifting’ water technique,

First, according to Rice University engineers, get a nanotube hole. Then insert water. If the nanotube is just the right width, the water molecules will align into a square rod.

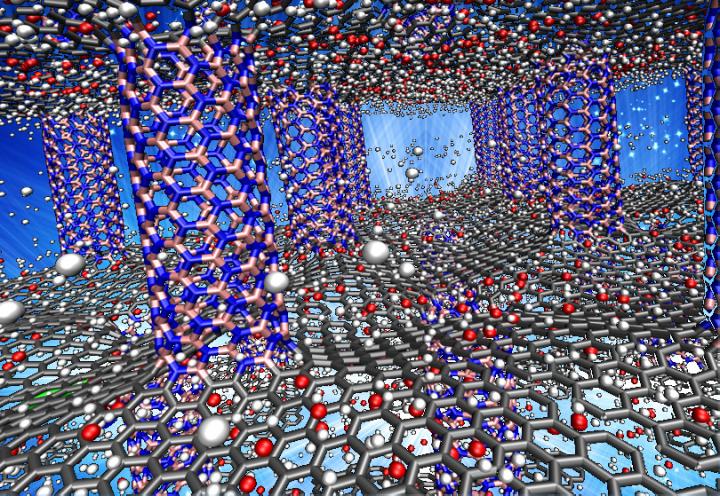

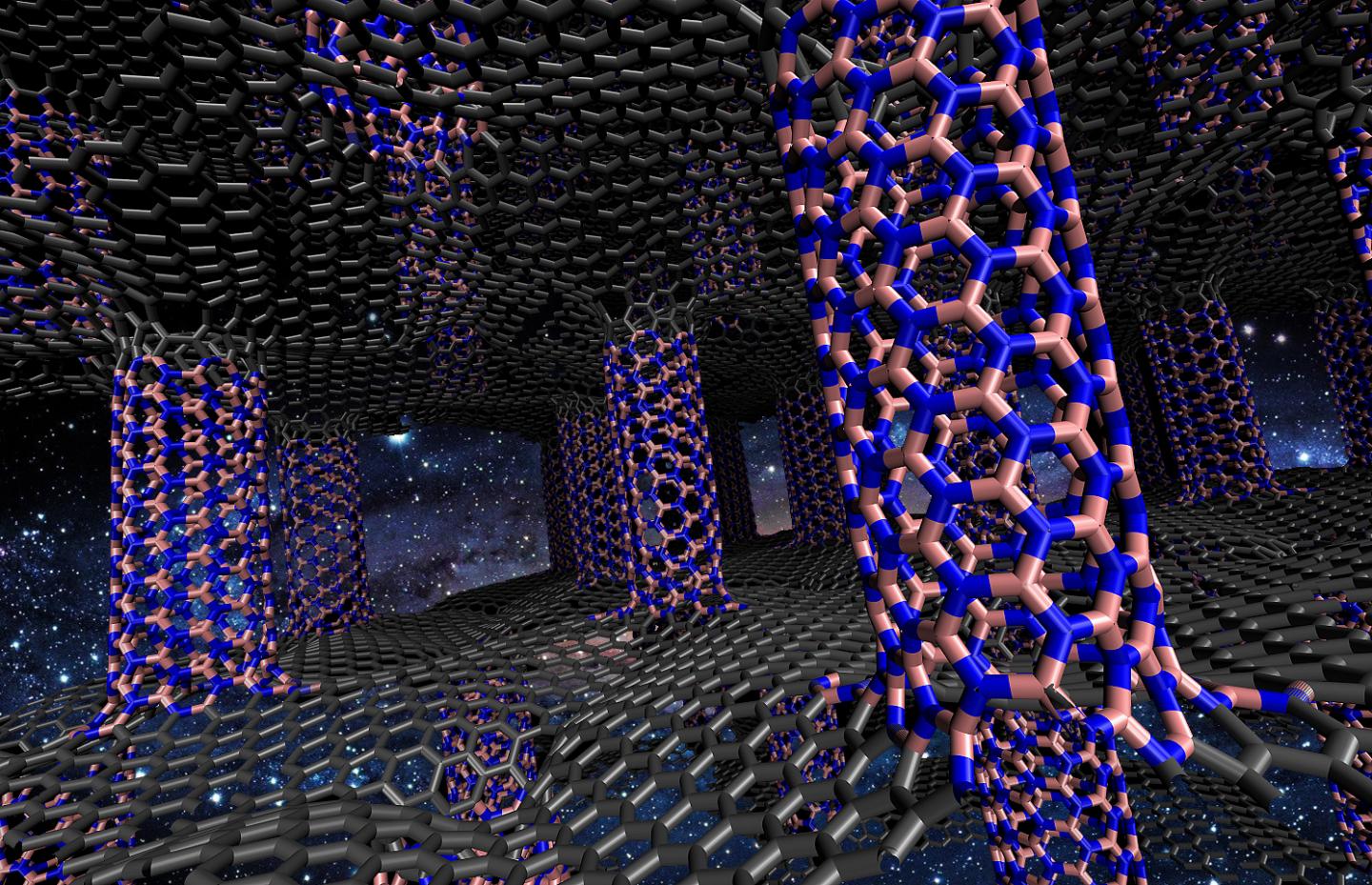

Rice materials scientist Rouzbeh Shahsavari and his team used molecular models to demonstrate their theory that weak van der Waals forces between the inner surface of the nanotube and the water molecules are strong enough to snap the oxygen and hydrogen atoms into place.

Shahsavari referred to the contents as two-dimensional “ice,” because the molecules freeze regardless of the temperature. He said the research provides valuable insight on ways to leverage atomic interactions between nanotubes and water molecules to fabricate nanochannels and energy-storing nanocapacitors.

An August 24, 2018 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert and received via email), which originated the news item, delves further,

Shahsavari and his colleagues built molecular models of carbon and boron nitride nanotubes with adjustable widths. They discovered boron nitride is best at constraining the shape of water when the nanotubes are 10.5 angstroms wide. (One angstrom is one hundred-millionth of a centimeter.)

The researchers already knew that hydrogen atoms in tightly confined water take on interesting structural properties. Recent experiments by other labs showed strong evidence for the formation of nanotube ice and prompted the researchers to build density functional theory models to analyze the forces responsible.

Shahsavari’s team modeled water molecules, which are about 3 angstroms wide, inside carbon and boron nitride nanotubes of various chiralities (the angles of their atomic lattices) and between 8 and 12 angstroms in diameter. They discovered that nanotubes in the middle diameters had the most impact on the balance between molecular interactions and van der Waals pressure that prompted the transition from a square water tube to ice.

“If the nanotube is too small and you can only fit one water molecule, you can’t judge much,” Shahsavari said. “If it’s too large, the water keeps its amorphous shape. But at about 8 angstroms, the nanotubes’ van der Waals force [if you’re not familiar with the term, see below the link and citation for my brief explanation] starts to push water molecules into organized square shapes.”

He said the strongest interactions were found in boron nitride nanotubes due to the particular polarization of their atoms.

Shahsavari said nanotube ice could find use in molecular machines or as nanoscale capillaries, or foster ways to deliver a few molecules of water or sequestered drugs to targeted cells, like a nanoscale syringe.

Lead author Farzaneh Shayeganfar, a former visiting scholar at Rice, is an instructor at Shahid Rajaee Teacher Training University in Tehran, Iran. Co-principal investigator Javad Beheshtian is a professor at Amirkabir University, Tehran.

Supercomputer resources were provided with support from the [US] National Institutes of Health and an IBM Shared Rice University Research grant.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

First Principles Study of Water Nanotubes Captured Inside Carbon/Boron Nitride Nanotubes by Farzaneh Shayeganfar, Javad Beheshtian, and Rouzbeh Shahsavari. Langmuir, DOI: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b00856 Publication Date (Web): August 23, 2018

Copyright © 2018 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

For the purposes of the posting, van der Waals force(s) are weak adhesive forces measured at the nanoscale. Humans don’t feel them (we’re too big) but gecko lizards can exploit those forces which is why they are able to hang from the ceiling by a single toe. There’s a more informed description here in the van der Waals force entry on Wikipedia.