Having written about memristors and neuromorphic engineering a number of times here, I’m quite intrigued to see some research into another nanoscale device for mimicking the functions of a human brain.

The announcement about the latest research from the team at the US Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory is in a Feb. 14, 2017 news item on Nanowerk (Note: A link has been removed),

Research published in Nature Scientific Reports (“Ferroelectric symmetry-protected multibit memory cell”) lays out a theoretical map to use ferroelectric material to process information using multivalued logic – a leap beyond the simple ones and zeroes that make up our current computing systems that could let us process information much more efficiently.

A Feb. 10, 2017 Argonne National Laboratory news release by Louise Lerner, which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

The language of computers is written in just two symbols – ones and zeroes, meaning yes or no. But a world of richer possibilities awaits us if we could expand to three or more values, so that the same physical switch could encode much more information.

“Most importantly, this novel logic unit will enable information processing using not only “yes” and “no”, but also “either yes or no” or “maybe” operations,” said Valerii Vinokur, a materials scientist and Distinguished Fellow at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory and the corresponding author on the paper, along with Laurent Baudry with the Lille University of Science and Technology and Igor Lukyanchuk with the University of Picardie Jules Verne.

This is the way our brains operate, and they’re something on the order of a million times more efficient than the best computers we’ve ever managed to build – while consuming orders of magnitude less energy.

“Our brains process so much more information, but if our synapses were built like our current computers are, the brain would not just boil but evaporate from the energy they use,” Vinokur said.

While the advantages of this type of computing, called multivalued logic, have long been known, the problem is that we haven’t discovered a material system that could implement it. Right now, transistors can only operate as “on” or “off,” so this new system would have to find a new way to consistently maintain more states – as well as be easy to read and write and, ideally, to work at room temperature.

Hence Vinokur and the team’s interest in ferroelectrics, a class of materials whose polarization can be controlled with electric fields. As ferroelectrics physically change shape when the polarization changes, they’re very useful in sensors and other devices, such as medical ultrasound machines. Scientists are very interested in tapping these properties for computer memory and other applications; but the theory behind their behavior is very much still emerging.

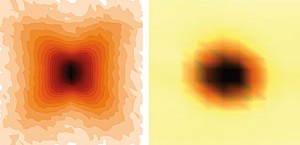

The new paper lays out a recipe by which we could tap the properties of very thin films of a particular class of ferroelectric material called perovskites.

According to the calculations, perovskite films could hold two, three, or even four polarization positions that are energetically stable – “so they could ‘click’ into place, and thus provide a stable platform for encoding information,” Vinokur said.

The team calculated these stable configurations and how to manipulate the polarization to move it between stable positions using electric fields, Vinokur said.

“When we realize this in a device, it will enormously increase the efficiency of memory units and processors,” Vinokur said. “This offers a significant step towards realization of so-called neuromorphic computing, which strives to model the human brain.”

Vinokur said the team is working with experimentalists to apply the principles to create a working system

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Ferroelectric symmetry-protected multibit memory cell by Laurent Baudry, Igor Lukyanchuk, & Valerii M. Vinokur. Scientific Reports 7, Article number: 42196 (2017) doi:10.1038/srep42196 Published online: 08 February 2017

This paper is open access.