Covering this art/sci piece in Saskatchewan proved to be an adventure that led from an evolutionary biologist in Saskatchewan to the Canadian Light Source to 3D models and fish to fractals and Fibonacci sequences to a Fransaskois video artist and sculptor and to much more.

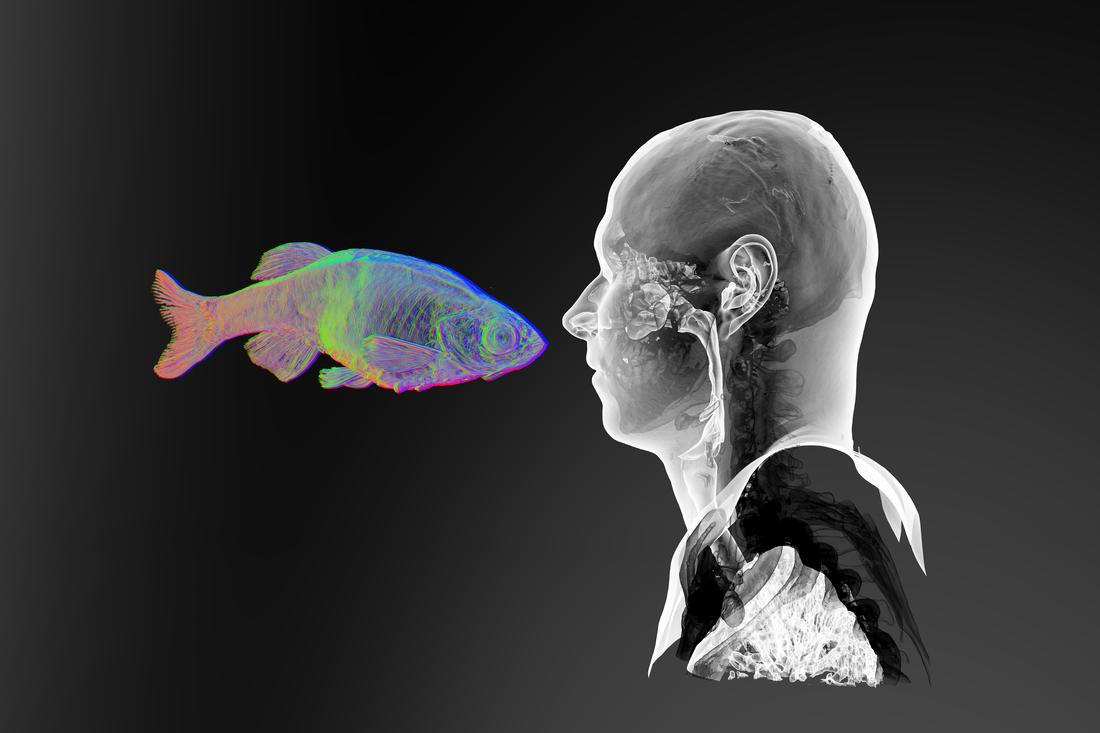

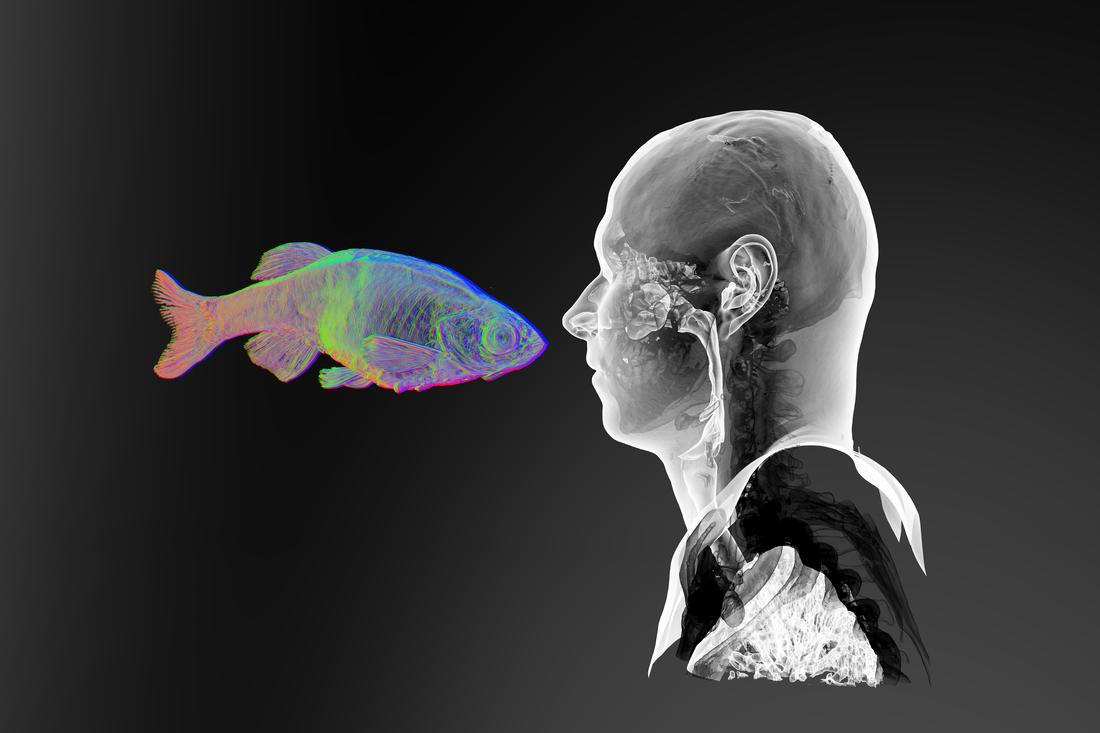

Starting from the end, there’s this,

“Face-to-Face 1” (2017). Digital rendering from synchrotron X-ray microtomography of adult zebrafish and CT scan of adult human. Image courtesy of JS Gauthier. [downloaded from https://www.sciartmagazine.com/collaboration-shining-a-light-on-unity.html]

Of course, it’s debatable as to whether this image could really be described as the end of anything especially since it’s referencing evolutionary biology. (The result of an art/sci project, the image is from the April 2017 exhibition, “Dans la Mesure / Within Measure,” by Jean-Sébastien Gauthier, and was hosted by the University of Saskatchewan College of Arts and Science at their Gordon Snelgrove Gallery.)

Perhaps it would be better to describe it as the end of the beginning which started when Gauthier (who’d been on a tour of the facility) posted a call for scientist collaborators in a Canadian Light Source (synchrotron) newsletter. From an October 2017 article by Erin Prosser-Loose for SciArt Magazine,

… The same day the newsletter went out he [Gautheir] received numerous replies, but one especially well-articulated response stood out to him.

Dr. Brian Eames in the College of Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan who kindly spoke with me at length about his involvement was the author of the letter which led, initially, to what sounds like a date. Eames and Gauthier met for coffee and conversation designed to gauge their compatibility. “We shared concepts on evolutionary biology and spitballed ideas for using the snychrotron to explore evolution.” Afterwards, they went to Eames’ laboratory where Gauthier was introduced to zebrafish in the lab’s downstairs aquaria.

Morphogenesis (the process that causes an organism to take its shape; for more see: this Wikipeida entry) was central to their first discussion and was the first working title for their project,

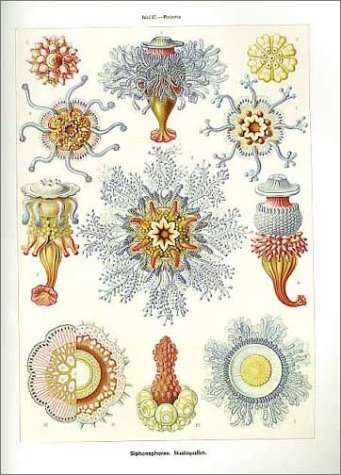

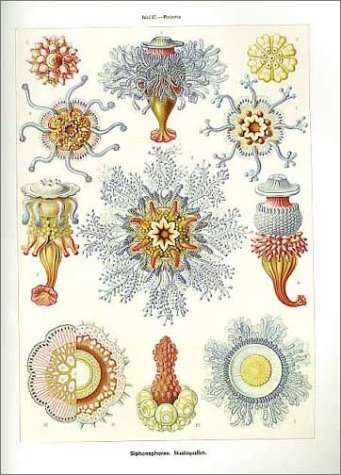

After their collaboration had been established, something serendipitous occurred. According to Gauthier, “We were imaging one of the first zebrafish samples in the lab when I noted the book on Brian’s desk in his office. It was a gift from PhD student, Patsy Gomez to Brian. It was an absolutely seminal point of reference for our work as it opened up a clear historical precedent for artsci.” “Art Forms in Nature: The Prints of Ernst Haeckel” was the book and, for anyone unfamiliar with Haeckel, he was a philosopher, a biologist, an artist, and more.

This description from the “Art Forms in Nature: The Prints of Ernst Haeckel’s” Amazon webpage gives some insight into the interplay between the artist and scientist that was Haeckel and which inspired the artist/scientist pairing of Gauthier and Eames almost 100 years after his death,

The geometric shapes and natural forms, captured with exceptional precision in Ernst Haeckel’s prints, still influence artists and designers to this day. This volume highlights the research and findings of this natural scientist. Powerful modern microscopes have confirmed the accuracy of Haeckel’s prints, which even in their day, became world famous. Haeckel’s portfolio, first published between 1899 and 1904 in separate installments, is described in the opening essays. The plates illustrate Haeckel’s fundamental monistic notion of the “unity of all living things” and the wide variety of forms are executed with utmost delicacy. Incipient microscopic organisms are juxtaposed with highly developed plants and animals. The pages, ordered according to geometric and “constructive” aspects, document the oness of the world in its most diversified forms. This collection of plates was not only well-received by scientists, but by artists and architects as well. Rene Binet, a pioneer of glass and iron constructions, Emile Galle, a renowned Art Nouveau designer, and the photographer Karl Blossfeld all make explicit reference to Haeckel in their work.

Here’s one of the images made available by Amazon,

[downloaded from https://www.amazon.com/Art-Forms-Nature-Prints-Haeckel/dp/3791319906]

Connectedness

‘Oneness’ and repetition of patterns? In mathematics, there are fractals and the Fibonacci sequence.

Fractals

The Fractal Foundation offers an explanation on their What are fractals? webpage,

A fractal is a never-ending pattern. Fractals are infinitely complex patterns that are self-similar across different scales. They are created by repeating a simple process over and over in an ongoing feedback loop. Driven by recursion, fractals are images of dynamic systems – the pictures of Chaos. Geometrically, they exist in between our familiar dimensions. Fractal patterns are extremely familiar, since nature is full of fractals. For instance: trees, rivers, coastlines, mountains, clouds, seashells, hurricanes, etc. Abstract fractals – such as the Mandelbrot Set – can be generated by a computer calculating a simple equation over and over.

[downloaded from http://fractalfoundation.org/2017/12/festive-fractals-show-128-at-7-pm/]

Fibonacci sequence

The Fibonacci sequence is another approach to connectedness (from the Temple University Math page on the Fibbonacci sequence, spirals and golden mean),

The story began in Pisa, Italy in the year 1202. Leonardo Pisano Bigollo was a young man in his twenties, a member of an important trading family of Pisa. In his travels throughout the Middle East, he was captivated by the mathematical ideas that had come west from India through the Arabic countries. When he returned to Pisa he published these ideas in a book on mathematics called Liber Abaci, which became a landmark in Europe. Leonardo, who has since come to be known as Fibonacci, became the most celebrated mathematician of the Middle Ages. His book was a discourse on mathematical methods in commerce, but is now remembered mainly for two contributions, one obviously important at the time and one seemingly insignificant.

The important one: he brought to the attention of Europe the Hindu system for writing numbers. European tradesmen and scholars were still clinging to the use of the old Roman numerals; modern mathematics would have been impossible without this change to the Hindu system, which we call now Arabic notation, since it came west through Arabic lands.

The other: hidden away in a list of brain-teasers , Fibonacci posed the following question:

If a pair of rabbits is placed in an enclosed area, how many rabbits will be born there if we assume that every month a pair of rabbits produces another pair, and that rabbits begin to bear young two months after their birth?

This apparently innocent little question has as an answer a certain sequence of numbers, known now as the Fibonacci sequence, which has turned out to be one of the most interesting ever written down. It has been rediscovered in an astonishing variety of forms, in branches of mathematics way beyond simple arithmetic. Its method of development has led to far-reaching applications in mathematics and computer science.

But even more fascinating is the surprising appearance of Fibonacci numbers, and their relative ratios, in arenas far removed from the logical structure of mathematics: in Nature and in Art, in classical theories of beauty and proportion.

As noted in my January 23, 2018 posting: What human speech, jazz, and whale song have in common and in my April 14, 2015 posting about gold nanoparticles and their resemblance to the Milky Way and DNA’s (deoxyribonucleic acid) double helix, repetitions and similarities can be found in many places .

Getting back to Brian Eames and Jean-Sébastien Gauthier, after exploring areas of mutual interest from a conversational perspective they went on to develop a project focused on unity and forms. “No matter what vertebrate (animals with bones) you compare, a chick or a mouse or a human or a zebrafish, they are very similar,” says Eames.

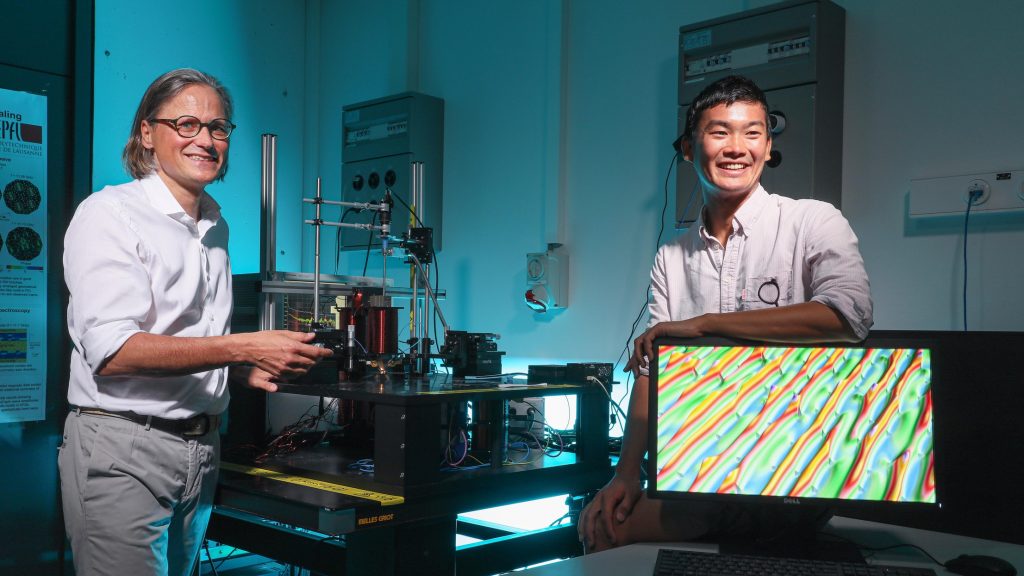

The scientist, the artist, and the synchrotron (Canadian Light Source)

Dr. Brian Eames

Eames’ research interests are, as noted on his faculty page where it’s Dr. Brian Eames, PhD., Faculty, Anatomy and Cell Biology, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan,

Research Areas

- Skeletal development and evolution

- molecular genetics

- synchrotron imaging

- 3D bioprinted tissue engineering

- Comparative transcriptomics

Specifically, Eames studies zebrafish and one of his main areas of research is (from an Oct. 23, 2017 article in the Saskatchewan Heath Research Foundation‘s publication, ‘Research for Health’, issue no. 4),

… defects associated with osteoarthritis that degrade the cartilage protecting the bones leaving them exposed and susceptible to damage. He did this in two ways: through the use of zebrafish embryos and with the cutting-edge imaging capabilities available at the synchrotron.

Originally from Ohio (US), Eames first studied at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where he developed an interest in virology at a time when HIV as a causative agent for AIDS was a hot topic. He went on to work at a Stanford University (California) laboratory before undertaking graduate studies at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) where he earned a PhD in Biomedical Sciences.

Eames discussed how his PhD was influenced by his earlier studies at UNC, “HIV taught me how genetic evolution worked, and I made a decision to study genetic evolution in a more complex system, the skeleton–so I picked a lab that studied skeletal development in the embryo for my PhD .” In fact, even before he’d studied HIV and genetic evolution in detail, Eames had a summer job after his second year in university where he worked on getting stem cells to differentiate into bone cells in a lab at Case Western Reserve University (iOhio).

He didn’t know it at the time but all all his research interests and work were to bring him to the University of Saskatchewan.

Jean-Sébastien Gauthier

Gauthier, by comparison, has a vastly different background and interests (from a biography page (PDF) on the Live Arts Saskatechewan website),

This dynamic program introduces students to new ways of making visual art. Using examples from contemporary and historical art, Jean-Sébastien will discuss performative approaches to art making. Students will learn how to create living sculptures from their own bodies and everyday materials, and will be inspired to use these temporary constructions as models for sketching and drawing.

…

Artist Biography

Jean-Sébastien (JS) Gauthier is a Fransaskois [Franco-Saskatchewanian] artist from Saskatoon. His art practice combines a range of disciplines, including sculpture, video, and performance. JS is the grandson of sculptor Bill Epp, well known for creating public sculpture for cities throughout Saskatchewan and the world. As a child JS apprenticed in his grandfather’s bronze foundry. After high school, JS studied animation, worked in a sculpture foundry in France, and studied Fine Arts at Concordia University in Montreal [Québec, Canada].

JS’s sculptures, videos, and performances have been exhibited throughout Canada, the US, and Europe. In 2014, he collaborated with two other Saskatoon artists to create a bronze monument titled «The Spirit of Alliance». This public work commemorates the alliance between First Nations People and the British Crown during the War of 1812.

In a sense, the Eames/Gauthier coffee date could have been described as Colliding Worlds (a 2014 book by Arthur I. Miller which is subtitled: How cutting edge science is redefining contemporary art) and was mentioned by Eames in his interview.

The resulting Gautheir/Eames collaboration has been celebrated in an interactive, immersive video installation exploring “developmental biology, evolution, and the complex unity between humans and other life forms, specifically the zebrafish.” (from the University of Saskatchewan exhibit description)

First, however, there was the science. “In the end he [Gauthier] did a science project and I was like a cheerleader encouraging him as he went through all the ups and downs of research,” said Eames. Both Eames and Gauthier had to develop new skills, Gauthier learning how to prepare samples, handle data, and process 3D scans while Eames refined his approach to preparing samples. ” We had to try a bunch of different techniques to ensure that the sample would stay still during the hours-long imaging sessions (if it moved even a little bit–a few microns [a micron is one millionth], then you can’t reconstruct 3D models of the sample!)–… JS got some art straws (used to protect art brushes during shipment), and then we’d immerse the sample in a seaweed jelly, put it in the straw, and seal the ends with melted wax. We also had to find the best settings [for] the imaging equipment (and the synchrotron equivalent equipment) to get the best resolution images possible.”

It’s all about the light

Synchrotrons are also known as ‘light sources’ and ours is the Canadian Light Source and for most Canadians finding out that Saskatoon is home to a world class facility and one of approximately 40 synchrotrons in the world (and the only one in Canada) will come as a bit of a shock. This description about synchrotrons from my May 31, 2011 posting about ours and the UK’s synchrotron still stands (the description can also be found on the Canadian Light Source’s What is a Synchrotron webpage),

A synchrotron is a source of brilliant light that scientists can use to gather information about the structural and chemical properties of materials at the molecular level.

A synchrotron produces the light by using powerful electro-magnets and radio frequency waves to accelerate electrons to nearly the speed of light. Energy is added to the electrons as they accelerate so that, when the magnets alter their course, they naturally emit a very brilliant, highly focused light. Different spectra of light, such as Infrared, Ultraviolet, and X-rays, are directed down beamlines where researchers choose the desired wavelength to study their samples. The researchers observe the interaction between the light and the matter in their sample at the endstations (small laboratories).

This tool can be used to probe the matter and analyze a host of physical, chemical, geological, and biological processes. Information obtained by scientists can be used to help design new drugs, examine the structure of surfaces to develop more effective motor oils, build smaller, more powerful computer chips, develop new materials for safer medical implants, and help with clean-up of mining wastes, to name just a few applications.

The Canadian Light Source’s Wikipedia entry provides some insight into the facility’s importance nationally (Note: Links have been removed),

The Canadian Light Source (CLS) (French: Centre canadien de rayonnement synchrotron – CCRS) is Canada’s national synchrotron light source facility, located on the grounds of the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.[1] The CLS has a third-generation 2.9 GeV storage ring, and the building occupies a footprint the size of a football field.[2] It opened in 2004 after a 30-year campaign by the Canadian scientific community to establish a synchrotron radiation facility in Canada.[3] It has expanded both its complement of beamlines and its building in two phases since opening, and its official visitors have included Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip. As a national synchrotron facility[4] with over 1000 individual users, it hosts scientists from all regions of Canada and around 20 other countries.[5] Research at the CLS has ranged from viruses[6] to superconductors[7] to dinosaurs,[8] and it has also been noted for its industrial science [9][10] and its high school education programs.[11]

Here’s an image of the synchrotron,

Synchrotron facility. Image credit Canadian Light Source Inc. [downloaded from https://www.sciartmagazine.com/collaboration-shining-a-light-on-unity.html]

The attraction for Eames, Gauthier, and countless scientists is the ability to see high resolution detail at extraordinarily small scales and, in some cases, to create 3D models using the data from the synchrotron. (After all, Gauthier is a sculptor and one of Eames’ research interests is molecular genetics.)

Prosser-Loose’s October 2017 article offers more detail about the collaboration,

The zebrafish is well known among biological scientists as a model organism for the study of developmental and genetic vertebrate biology. Using zebrafish in the project began for practical reasons as Brian had access to a large quantity of the embryos, which would be important for trouble shooting imaging techniques and for use on the synchrotron. From his perspective, JS [Gauthier] liked the idea of using a well-characterized, scientific model organism for his art, “As an artist, I believe that anything can be significant to my art practice, that I don’t need to have reasons beyond curious engagement to undertake explorations. …”

The first step was to image the zebrafish embryo in 3D. As Brian [Eames] explains, “the basic idea is that you stabilize the sample (the zebrafish embryo) by embedding it in a thick gel, so that it doesn’t move, put it on something like a record player, and take a series of X-rays, rotating the sample slightly each time.” From these 2D images, JS utilized software to make 3D models. For the interactive piece project, the 3D images were further processed through a mix of sculpting and rendering software, which made them useable in an interactive game engine. …

Before moving onto the art and because it fascinates me, here are a few quick facts about the Canadian Light Source (CLS) from their What is a Synchrotron webpage),

- … The Canadian synchrotron is competitive with the brightest facilities in Japan, the U.S. and Europe.

- …

- More than 3,000 scientists have used the CLS more than 5,000 times.

- Beamlines carry the synchrotron light to scientific work stations that operate 24 hours per day, 6 days per week, approximately 42 weeks of the year.

- …

- CLS utility costs are approximately $1.8M annually including electricity, steam and water. When we are operating the facility with stored beam, consumption is approximately 3.2-3.5 megawatts to produce approximately 200 kW of synchrotron radiation. This translates to approximately $1,000 worth of electricity daily.

- The six-storey building (Phase I construction) required 1,300 tons of steel and enough concrete to build 160 1,200-square-foot homes. This concrete base has more than 700 piles each 10-20m deep with vibrational isolation from the foundation for the walls in order to ensure stability.

- A 2010 economic impact study estimated that CLS operations directly contributed almost $90M to the Canadian GDP. This means that for every dollar of CLS operating funding (approximately $23M) our operations contributed three to the Canadian economy.

As for the ‘light’ produced by a synchrotron, Eames describes it this way, “It’s like an x-ray but the source in this case is more intense. The term is “brilliance” for the brightness and other qualities of the synchrotron light, no joke.”

The art/sci piece: Dans la Mesure / Within Measure and beyond

This video gives a little insight into how the senses (sight, hearing, and kinesthetia) are engaged by “Dans la Mesure / Within Measure”,

The sound you hear in the video is from a session when musician and sound artist Andy Rudolph had Eames and Gauthier place a microphone in the synchrotron to record the sound while they were imaging one of their samples.

In a later (after the University of Saskatchewan exhibit in April 2017) , simultaneous installation of Dans la Mesure / Within Measure at la ‘Nuit Blanche Saskatoon‘ and la ‘Nuit Blanche Toronto‘ on September 30, 2017, Gauthier said there were, “… proximity sensors [or] ultrasonic rangefinders. They detect[ed] viewers’ positions using high frequency sonar. The sensors were in plain view, (though their function was not made evident to the audience, unless someone was interacting with them at that particular time). These sensors didn’t really “activate the projector”; they would translate and magnify the scale and rotation of embryonic 3D models from a single pixel on the wall to a monumental scale. The default single pixel projections were still bigger than the most of the actual samples that were modelled ,so the display played upon senses of scale also. The proximity of the viewer also alter[ed] the volume and location of audio samples in the soundscape.” In effect, the viewer would experience the development of a zebrafish embryo by walking through a series of eight 3D models

In summing up the idea behind the Eames/Guathier project and, in reality, all artists and scientists working in collaboration, Jeff Cutler (CLS [Canadian Light Source] Chief Strategic Relations officer) in Prosser-Loose’s October 2017 article does a beautiful job,

… “Art and science are natural collaborators. In the same way that art alters a perspective, or provides an unexpected revelation, so does science. Researchers from around the world come to our light source in order to see things differently, and their findings often change how we look at the world. It’s this search for a new way of seeing things that brings art and science together, and that’s why it’s important for us to work with artists like JS. Not only does his work introduce the CLS to a new audience, but he has also challenged us to see our own work differently.”

Eames adds to the reasons for art/sci collaboration,

“My work depends upon taxpayer money! So really, everyone should get something from my work, since they paid for it. What can they get out of it? Well, the synchrotron is an amazing investment by Canadians that provides unique and wonderfully insightful views of all sorts of things in the world. The fact that it’s in Saskatoon should bring even more pride to the people of Saskatchewan. Also, JS and I feel strongly that many problems that humans have today are due to a lack of understanding of how all forms of life are related, so this is a major driving force in our collaboration so far.”

Beyond (future plans)

Eames and Gauthier have big plans for what comes next. Building on their first project, which was supported by a Canada Council for the Arts grant, they are currently embarking on a more technically complex piece with more sculptures and more viewer interaction with the objects. Their aim is to heighten the immersive and interactive experience.

They’re planning to make greater interaction possible through [augmented] reality (AR)* which will engage viewers in a sensory field, as well as, allowing accessibility outside of a gallery. Similar to their first installation, Eames and Gauthier are also planning a generative soundscape based on viewers’ position in the gallery.

In November 2017, Eames and Gauthier received the news that “All Forms at All Times / Toutes formes et en tout temps” had received funding from the Canada Council for the Arts with contributions from the University of Saskatchewan.

This time, specimens from other species will be included. As Eames explains about this new work, ” [We’re once again] hitting the commonality of life on Earth…plus I find that each animal’s embryos has its unique beauties; I’m very interested to see how JS puts the various images together aesthetically.”

Final thoughts

it’s exciting to hear of this art/sci work (or SciArt as it’s sometimes called) in Saskatchewan. There seems to be a movement in Canada building towards these kinds of collaborations and interactions. There’s Curiosity Collider which holds events in Vancouver (BC); Beakerhead, a five-day art, science, and engineering festival held in Calgary (Alberta) annually since 2013, the Art/Sci Salon holds events in Toronto (Ontario), and Art the Science; “a Canadian Science-Art nonprofit (likely in Ontario), which helps set up artist residencies in science facilities. Art the Science has regularly updated blog featuring creators and various Science-Art projects.

This isn’t the first time there’s been an art/sci ‘movement’ in Canada. About 15 or 20 years ago (in the early 2000’s), the Canada Council for the Arts worked with Canada’s Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) and the National Research Council (NRC) of Canada to award grants for art/sci collaborations and for artist residencies in science facilities.

At the time, I spoke with artist Alan Storey who had a residency at TRIUMF (if memory serves) which is now billing itself as “Canada’s particle accelerator centre.” (It was “Canada’s National Laboratory for Particle and Nuclear Physics”.) He was a bit discouraged as there wasn’t much interest in anything other than his welding skills (artists often need to develop a broad range of skills to realize their artistic vision and to support themselves). The grants programme died within a year or two after that. So, it’s great to see an art/sci (or SciArt) movement taking place now in what seems to have been a bottom-up process (or what used to be called a grassroots movement).

As mentioned earlier in this posting, the notion of exploring connections between various natural forms has long held great interest for me. The experiential element of the exhibit underscores the notion of connections between the viewer and the object while giving the viewer something more to do than gaze at art works. There’s nothing wrong with gazing at art works; it can be a very powerful experience but “Dans la Mesure / Within Measure” arises from ideas about evolutionary biology and it could be said that biology and evolution are about movement (especially given Eames’ research into knee cartilage) and change.

Gauthier and Eames have created a very male installation. All of the figures I’ve seen in the video and in Prosser-Loose’s October 2017 article (I encourage you to read it if you have time; my excerpts don’t do justice to it and the many images embedded in it) feature what appear to be male figures only. It’s an unexpected approach since females are usually associated with embryos and reproduction. It challenges preconceptions about reproduction and, by extension, evolutionary biology in some subtle ways.

Of course, there may have been purely practical reasons for using a male figure throughout. Cost and convernience. It’s the same reason zerbrafish embryos were used. Anyway, it will be interesting to note if more funding will affect the ‘figures’ in future projects.

Connect to and/or presenting “Dans la Mesure / Within Measure”?

For anyone interested in hosting “Dans la Mesure / Within Measure,” Gauthier and Eames are very interested in bringing their work to new venues.

Contact either the artist or the scientist:

JS Gauthier:

videosculpture@gmail.com

jsgauthier.com

Brian Eames:

b.frank@usask.ca

www.eameslab.ca

https://medicine.usask.ca/profiles/anatomy-and-cell-biology/brian-eames.php

You can also preview the installation online (although these things do tend to be somewhat site specific),

video of the project at: vimeo.com/jsgauthier

Added bonus:

3d models from the collaboration at

sketchfab.com/jsgauthier

Breaking news

Eames and Gauthier are currently in talks with Calgary’s Beakerhead to present their newest, “All Forms at All Times / Toutes formes et en tout temps” as part of the Beakerhead festival in Calgary, September 19 -23, 2018. Details are still being discussed. Meanwhile, an exhibition for the news installation is being planned for early 2019.

*AR/MR/VR stand for augmented reality, mixed reality, and virtual reality respectively. While VR, which requires equipment such as specialized helmets and induce immersion in a ‘counterfeit reality’ has a largely standard definition, AR and MR do not with AR and MR sometimes being used interchangeably to describe a reality composed of ‘real’ and ‘counterfeit’ elements. You’ll get much better definitions from foundry.com’s VR? AR? MR? Sorry I’m confused webpage.