In the years since this blog began (2006), there’ve been pretty regular postings about nanosunscreens. While there are always concerns about nanoparticles and health, there has been no evidence to support a ban (personal or governmental) on nanosunscreens. A June 2016 report by Paul FA Wright (full reference information to follow) in an Australian medical journal provides the latest insights on safety and nanosunscreens. Wright first offers a general introduction to risks and nanomaterials (Note: Links have been removed),

In reality, a one-size-fits-all approach to evaluating the potential risks and benefits of nanotechnology for human health is not possible because it is both impractical and would be misguided. There are many types of engineered nanomaterials, and not all are alike or potential hazards. Many factors should be considered when evaluating the potential risks associated with an engineered nanomaterial: the likelihood of being exposed to nanoparticles (ranging in size from 1 to 100 nanometres, about one-thousandth of the width of a human hair) that may be shed by the nanomaterial; whether there are any hotspots of potential exposure to shed nanoparticles over the whole of the nanomaterial’s life cycle; identifying who or what may be exposed; the eventual fate of the shed nanoparticles; and whether there is a likelihood of adverse biological effects arising from these exposure scenarios.1

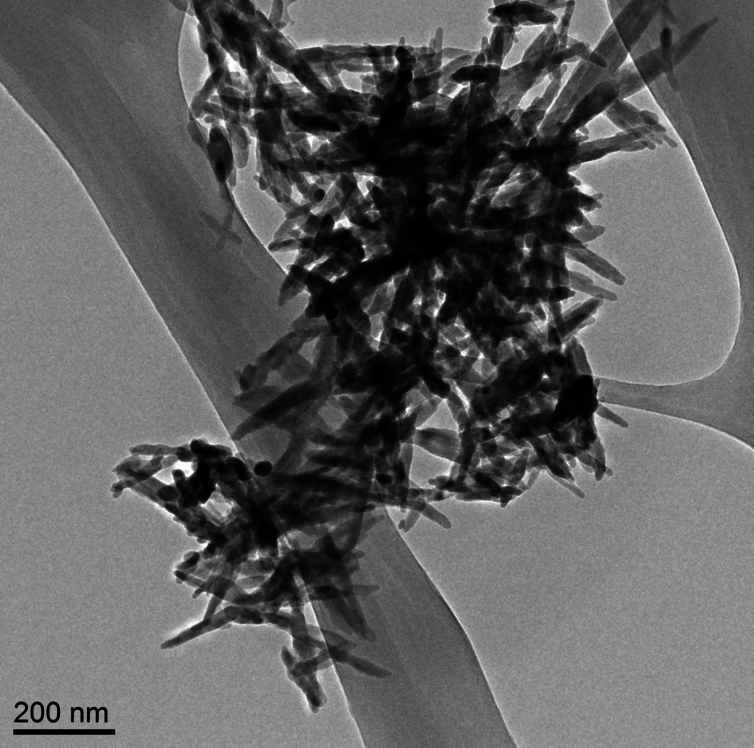

The intrinsic toxic properties of compounds contained in the nanoparticle are also important, as well as particle size, shape, surface charge and physico-chemical characteristics, as these greatly influence their uptake by cells and the potential for subsequent biological effects. In summary, nanoparticles are more likely to have higher toxicity than bulk material if they are insoluble, penetrate biological membranes, persist in the body, or (where exposure is by inhalation) are long and fibre-like.1 Ideally, nanomaterial development should incorporate a safety-by-design approach, as there is a marketing edge for nano-enabled products with a reduced potential impact on health and the environment.1

Wright also covers some of nanotechnology’s hoped for benefits but it’s the nanosunscreen which is the main focus of this paper (Note: Links have been removed),

Public perception of the potential risks posed by nanotechnology is very different in certain regions. In Asia, where there is a very positive perception of nanotechnology, some products have been marketed as being nano-enabled to justify charging a premium price. This has resulted in at least four Asian economies adopting state-operated, user-financed product testing schemes to verify nano-related marketing claims, such as the original “nanoMark” certification system in Taiwan.4

In contrast, the negative perception of nanotechnology in some other regions may result in questionable marketing decisions; for example, reducing the levels of zinc oxide nanoparticles included as the active ingredient in sunscreens. This is despite their use in sunscreens having been extensively and repeatedly assessed for safety by regulatory authorities around the world, leading to their being widely accepted as safe to use in sunscreens and lip products.5

Wright goes on to describe the situation in Australia (Note: Links have been removed),

Weighing the potential risks and benefits of using sunscreens with UV-filtering nanoparticles is an important issue for public health in Australia, which has the highest rate of skin cancer in the world as the result of excessive UV exposure. Some consumers are concerned about using these nano-sunscreens,6 despite their many advantages over conventional organic chemical UV filters, which can cause skin irritation and allergies, need to be re-applied more frequently, and are absorbed by the skin to a much greater extent (including some with potentially endocrine-disrupting activity). Zinc oxide nanoparticles are highly suitable for use in sunscreens as a physical broad spectrum UV filter because of their UV stability, non-irritating nature, hypo-allergenicity and visible transparency, while also having a greater UV-attenuating capacity than bulk material (particles larger than 100 nm in diameter) on a per weight basis.7

Concerns about nano-sunscreens began in 2008 with a report that nanoparticles in some could bleach the painted surfaces of coated steel.8 This is a completely different exposure situation to the actual use of nano-sunscreen by people; here they are formulated to remain on the skin’s surface, which is constantly shedding its outer layer of dead cells (the stratum corneum). Many studies have shown that metal oxide nanoparticles do not readily penetrate the stratum corneum of human skin, including a hallmark Australian investigation by Gulson and co-workers of sunscreens containing only a less abundant stable isotope of zinc that allowed precise tracking of the fate of sunscreen zinc.9 The researchers found that there was little difference between nanoparticle and bulk zinc oxide sunscreens in the amount of zinc absorbed into the body after repeated skin application during beach trials. The amount absorbed was also extremely small when compared with the normal levels of zinc required as an essential mineral for human nutrition, and the rate of skin absorption was much lower than that of the more commonly used chemical UV filters.9 Animal studies generally find much higher skin absorption of zinc from dermal application of zinc oxide sunscreens than do human studies, including the meticulous studies in hairless mice conducted by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) using both nanoparticle and bulk zinc oxide sunscreens that contained the less abundant stable zinc isotope.10 These researchers reported that the zinc absorbed from sunscreen was distributed throughout several major organs, but it did not alter their total zinc concentrations, and that overall zinc homeostasis was maintained.10

He then discusses titanium dioxide nanoparticles (also used in nanosunscreens, Note: Links have been removed),

The other metal oxide UV filter is titanium dioxide. Two distinct crystalline forms have been used: the photo-active anatase form and the much less photo-active rutile form,7 which is preferable for sunscreen formulations. While these insoluble nanoparticles may penetrate deeper into the stratum corneum than zinc oxide, they are also widely accepted as being safe to use in non-sprayable sunscreens.11

Investigation of their direct effects on human skin and immune cells have shown that sunscreen nanoparticles of zinc oxide and rutile titanium dioxide are as well tolerated as zinc ions and conventional organic chemical UV filters in human cell test systems.12 Synchrotron X-ray fluorescence imaging has also shown that human immune cells break down zinc oxide nanoparticles similar to those in nano-sunscreens, indicating that immune cells can handle such particles.13 Cytotoxicity occurred only at very high concentrations of zinc oxide nanoparticles, after cellular uptake and intracellular dissolution,14 and further modification of the nanoparticle surface can be used to reduce both uptake by cells and consequent cytotoxicity.15

The ongoing debate about the safety of nanoparticles in sunscreens raised concerns that they may potentially increase free radical levels in human skin during co-exposure to UV light.6 On the contrary, we have seen that zinc oxide and rutile titanium dioxide nanoparticles directly reduce the quantity of damaging free radicals in human immune cells in vitro when they are co-exposed to the more penetrating UV-A wavelengths of sunlight.16 We also identified zinc-containing nanoparticles that form immediately when dissolved zinc ions are added to cell culture media and pure serum, which suggests that they may even play a role in natural zinc transport.17

Here’s a link to and a citation for Wright’s paper,

Potential risks and benefits of nanotechnology: perceptions of risk in sunscreens by Paul FA Wright. Med J Aust 2016; 204 (10): 369-370. doi:10.5694/mja15.01128 Published June 6, 2016

This paper appears to be open access.

The situation regarding perceptions of nanosunscreens in Australia was rather unfortunate as I noted in my Feb. 9, 2012 posting about a then recent government study which showed that some Australians were avoiding all sunscreens due to fears about nanoparticles. Since then Friends of the Earth seems to have moderated its stance on nanosunscreens but there is a July 20, 2010 posting (includes links to a back-and-forth exchange between Dr. Andrew Maynard and Friends of the Earth representatives) which provides insight into the ‘debate’ prior to the 2012 ‘debacle’. For a briefer overview of the situation you could check out my Oct. 4, 2012 posting.