Markus Buehler at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has been working with music and science for a number of years. My December 9, 2011 posting, Music, math, and spiderwebs, was the first one here featuring his work. My November 28, 2012 posting, Producing stronger silk musically, was a followup to Buehler’s previous work.

A June 28, 2019 news item on Azonano provides a recent update,

Composers string notes of different pitch and duration together to create music. Similarly, cells join amino acids with different characteristics together to make proteins.

Now, researchers have bridged these two seemingly disparate processes by translating protein sequences into musical compositions and then using artificial intelligence to convert the sounds into brand-new proteins. …

A June 26, 2019 American Chemical Society (ACS) news release, which originated the news item, provides more detail and a video,

To make proteins, cellular structures called ribosomes add one of 20 different amino acids to a growing chain in combinations specified by the genetic blueprint. The properties of the amino acids and the complex shapes into which the resulting proteins fold determine how the molecule will work in the body. To better understand a protein’s architecture, and possibly design new ones with desired features, Markus Buehler and colleagues wanted to find a way to translate a protein’s amino acid sequence into music.

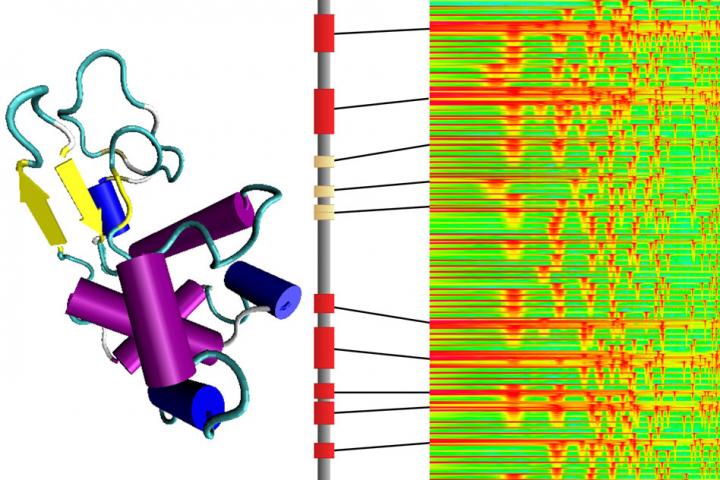

The researchers transposed the unique natural vibrational frequencies of each amino acid into sound frequencies that humans can hear. In this way, they generated a scale consisting of 20 unique tones. Unlike musical notes, however, each amino acid tone consisted of the overlay of many different frequencies –– similar to a chord. Buehler and colleagues then translated several proteins into audio compositions, with the duration of each tone specified by the different 3D structures that make up the molecule. Finally, the researchers used artificial intelligence to recognize specific musical patterns that corresponded to certain protein architectures. The computer then generated scores and translated them into new-to-nature proteins. In addition to being a tool for protein design and for investigating disease mutations, the method could be helpful for explaining protein structure to broad audiences, the researchers say. They even developed an Android app [Amino Acid Synthesizer] to allow people to create their own bio-based musical compositions.

Here’s the ACS video,

A June 26, 2019 MIT news release (also on EurekAlert) provides some specifics and the MIT news release includes two embedded audio files,

Want to create a brand new type of protein that might have useful properties? No problem. Just hum a few bars.

In a surprising marriage of science and art, researchers at MIT have developed a system for converting the molecular structures of proteins, the basic building blocks of all living beings, into audible sound that resembles musical passages. Then, reversing the process, they can introduce some variations into the music and convert it back into new proteins never before seen in nature.

Although it’s not quite as simple as humming a new protein into existence, the new system comes close. It provides a systematic way of translating a protein’s sequence of amino acids into a musical sequence, using the physical properties of the molecules to determine the sounds. Although the sounds are transposed in order to bring them within the audible range for humans, the tones and their relationships are based on the actual vibrational frequencies of each amino acid molecule itself, computed using theories from quantum chemistry.

The system was developed by Markus Buehler, the McAfee Professor of Engineering and head of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at MIT, along with postdoc Chi Hua Yu and two others. As described in the journal ACS Nano, the system translates the 20 types of amino acids, the building blocks that join together in chains to form all proteins, into a 20-tone scale. Any protein’s long sequence of amino acids then becomes a sequence of notes.

While such a scale sounds unfamiliar to people accustomed to Western musical traditions, listeners can readily recognize the relationships and differences after familiarizing themselves with the sounds. Buehler says that after listening to the resulting melodies, he is now able to distinguish certain amino acid sequences that correspond to proteins with specific structural functions. “That’s a beta sheet,” he might say, or “that’s an alpha helix.”

Learning the language of proteins

The whole concept, Buehler explains, is to get a better handle on understanding proteins and their vast array of variations. Proteins make up the structural material of skin, bone, and muscle, but are also enzymes, signaling chemicals, molecular switches, and a host of other functional materials that make up the machinery of all living things. But their structures, including the way they fold themselves into the shapes that often determine their functions, are exceedingly complicated. “They have their own language, and we don’t know how it works,” he says. “We don’t know what makes a silk protein a silk protein or what patterns reflect the functions found in an enzyme. We don’t know the code.”

By translating that language into a different form that humans are particularly well-attuned to, and that allows different aspects of the information to be encoded in different dimensions — pitch, volume, and duration — Buehler and his team hope to glean new insights into the relationships and differences between different families of proteins and their variations, and use this as a way of exploring the many possible tweaks and modifications of their structure and function. As with music, the structure of proteins is hierarchical, with different levels of structure at different scales of length or time.

The team then used an artificial intelligence system to study the catalog of melodies produced by a wide variety of different proteins. They had the AI system introduce slight changes in the musical sequence or create completely new sequences, and then translated the sounds back into proteins that correspond to the modified or newly designed versions. With this process they were able to create variations of existing proteins — for example of one found in spider silk, one of nature’s strongest materials — thus making new proteins unlike any produced by evolution.

Although the researchers themselves may not know the underlying rules, “the AI has learned the language of how proteins are designed,” and it can encode it to create variations of existing versions, or completely new protein designs, Buehler says. Given that there are “trillions and trillions” of potential combinations, he says, when it comes to creating new proteins “you wouldn’t be able to do it from scratch, but that’s what the AI can do.”

“Composing” new proteins

By using such a system, he says training the AI system with a set of data for a particular class of proteins might take a few days, but it can then produce a design for a new variant within microseconds. “No other method comes close,” he says. “The shortcoming is the model doesn’t tell us what’s really going on inside. We just know it works.

This way of encoding structure into music does reflect a deeper reality. “When you look at a molecule in a textbook, it’s static,” Buehler says. “But it’s not static at all. It’s moving and vibrating. Every bit of matter is a set of vibrations. And we can use this concept as a way of describing matter.”

The method does not yet allow for any kind of directed modifications — any changes in properties such as mechanical strength, elasticity, or chemical reactivity will be essentially random. “You still need to do the experiment,” he says. When a new protein variant is produced, “there’s no way to predict what it will do.”

The team also created musical compositions developed from the sounds of amino acids, which define this new 20-tone musical scale. The art pieces they constructed consist entirely of the sounds generated from amino acids. “There are no synthetic or natural instruments used, showing how this new source of sounds can be utilized as a creative platform,” Buehler says. Musical motifs derived from both naturally existing proteins and AI-generated proteins are used throughout the examples, and all the sounds, including some that resemble bass or snare drums, are also generated from the sounds of amino acids.

The researchers have created a free Android smartphone app, called Amino Acid Synthesizer, to play the sounds of amino acids and record protein sequences as musical compositions.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A Self-Consistent Sonification Method to Translate Amino Acid Sequences into Musical Compositions and Application in Protein Design Using Artificial Intelligence by Chi-Hua Yu, Zhao Qin, Francisco J. Martin-Martinez, Markus J. Buehler. ACS Nano 2019 XXXXXXXXXX-XXX DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b02180 Publication Date:June 26, 2019 Copyright © 2019 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

ETA October 23, 2019 1000 hours: Ooops! I almost forgot the link to the Aminot Acid Synthesizer.