Scientists working on The Materials Project have taken the notion of open science to their hearts and opened up access to their data according to a June 9, 2016 news item on Nanowerk,

The Materials Project, a Google-like database of material properties aimed at accelerating innovation, has released an enormous trove of data to the public, giving scientists working on fuel cells, photovoltaics, thermoelectrics, and a host of other advanced materials a powerful tool to explore new research avenues. But it has become a particularly important resource for researchers working on batteries. Co-founded and directed by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) scientist Kristin Persson, the Materials Project uses supercomputers to calculate the properties of materials based on first-principles quantum-mechanical frameworks. It was launched in 2011 by the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Office of Science.

A June 8, 2016 Berkeley Lab news release, which originated the news item, provides more explanation about The Materials Project,

The idea behind the Materials Project is that it can save researchers time by predicting material properties without needing to synthesize the materials first in the lab. It can also suggest new candidate materials that experimentalists had not previously dreamed up. With a user-friendly web interface, users can look up the calculated properties, such as voltage, capacity, band gap, and density, for tens of thousands of materials.

…

Two sets of data were released last month: nearly 1,500 compounds investigated for multivalent intercalation electrodes and more than 21,000 organic molecules relevant for liquid electrolytes as well as a host of other research applications. Batteries with multivalent cathodes (which have multiple electrons per mobile ion available for charge transfer) are promising candidates for reducing cost and achieving higher energy density than that available with current lithium-ion technology.

The sheer volume and scope of the data is unprecedented, said Persson, who is also a professor in UC Berkeley’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering. “As far as the multivalent cathodes, there’s nothing similar in the world that exists,” she said. “To give you an idea, experimentalists are usually able to focus on one of these materials at a time. Using calculations, we’ve added data on 1,500 different compositions.”

While other research groups have made their data publicly available, what makes the Materials Project so useful are the online tools to search all that data. The recent release includes two new web apps—the Molecules Explorer and the Redox Flow Battery Dashboard—plus an add-on to the Battery Explorer web app enabling researchers to work with other ions in addition to lithium.

“Not only do we give the data freely, we also give algorithms and software to interpret or search over the data,” Persson said.

The Redox Flow Battery app gives scientific parameters as well as techno-economic ones, so battery designers can quickly rule out a molecule that might work well but be prohibitively expensive. The Molecules Explorer app will be useful to researchers far beyond the battery community.

“For multivalent batteries it’s so hard to get good experimental data,” Persson said. “The calculations provide rich and robust benchmarks to assess whether the experiments are actually measuring a valid intercalation process or a side reaction, which is particularly difficult for multivalent energy technology because there are so many problems with testing these batteries.”

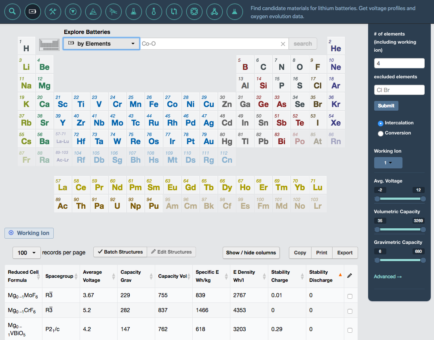

Here’s a screen capture from the Battery Explorer app,

The Materials Project’s Battery Explorer app now allows researchers to work with other ions in addition to lithium. Courtesy: The Materials Project

The news release goes on to describe a new discovery made possible by The Materials Project (Note: A link has been removed),

Together with Persson, Berkeley Lab scientist Gerbrand Ceder, postdoctoral associate Miao Liu, and MIT graduate student Ziqin Rong, the Materials Project team investigated some of the more promising materials in detail for high multivalent ion mobility, which is the most difficult property to achieve in these cathodes. This led the team to materials known as thiospinels. One of these thiospinels has double the capacity of the currently known multivalent cathodes and was recently synthesized and tested in the lab by JCESR researcher Linda Nazar of the University of Waterloo, Canada.

“These materials may not work well the first time you make them,” Persson said. “You have to be persistent; for example you may have to make the material very phase pure or smaller than a particular particle size and you have to test them under very controlled conditions. There are people who have actually tried this material before and discarded it because they thought it didn’t work particularly well. The power of the computations and the design metrics we have uncovered with their help is that it gives us the confidence to keep trying.”

The researchers were able to double the energy capacity of what had previously been achieved for this kind of multivalent battery. The study has been published in the journal Energy & Environmental Science in an article titled, “A High Capacity Thiospinel Cathode for Mg Batteries.”

“The new multivalent battery works really well,” Persson said. “It’s a significant advance and an excellent proof-of-concept for computational predictions as a valuable new tool for battery research.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A high capacity thiospinel cathode for Mg batteries by Xiaoqi Sun, Patrick Bonnick, Victor Duffort, Miao Liu, Ziqin Rong, Kristin A. Persson, Gerbrand Ceder and Linda F. Nazar. Energy Environ. Sci., 2016, Advance Article DOI: 10.1039/C6EE00724D First published online 24 May 2016

This paper seems to be behind a paywall.

Getting back to the news release, there’s more about The Materials Project in relationship to its membership,

The Materials Project has attracted more than 20,000 users since launching five years ago. Every day about 20 new users register and 300 to 400 people log in to do research.

One of those users is Dane Morgan, a professor of engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who develops new materials for a wide range of applications, including highly active catalysts for fuel cells, stable low-work function electron emitter cathodes for high-powered microwave devices, and efficient, inexpensive, and environmentally safe solar materials.

“The Materials Project has enabled some of the most exciting research in my group,” said Morgan, who also serves on the Materials Project’s advisory board. “By providing easy access to a huge database, as well as tools to process that data for thermodynamic predictions, the Materials Project has enabled my group to rapidly take on materials design projects that would have been prohibitive just a few years ago.”

More materials are being calculated and added to the database every day. In two years, Persson expects another trove of data to be released to the public.

“This is the way to reach a significant part of the research community, to reach students while they’re still learning material science,” she said. “It’s a teaching tool. It’s a science tool. It’s unprecedented.”

Supercomputing clusters at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a DOE Office of Science User Facility hosted at Berkeley Lab, provide the infrastructure for the Materials Project.

Funding for the Materials Project is provided by the Office of Science (US Department of Energy], including support through JCESR [Joint Center for Energy Storage Research].

Happy researching!