All three of these University of Waterloo (UW) startups could be said to feature windows in one fashion or another but it is a bit of a stretch to describe their products as ‘window-oriented’ since these entrepreneurs have big plans.

The first company I’m mentioning is Lumotune, a company whose homepage features NanoShutters and this tagline, “Smarter Glass for a Smarter World”. A Dec. 10, 2013 article by Terry Pender for GuelphMercury.com provides a description of this product which is controlled by a smartphone application,

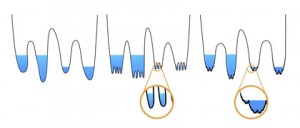

The product is made of two thin sheets of clear plastic. In between the sheets is the nanotechnology the trio started developing as a school project. The optics of the glass can easily be changed from clear to opaque using a laptop, tablet or smartphone.

The NanoShutters adhere to a window and are connected to a control box with tiny wires. The control box can be plugged into a laptop or controlled wirelessly with tablets and smartphones.

The control box is the most important part of the NanoShutters; the founders have applied for a patent to protect their ownership of it.

“That is basically the core technology,” Esfahani said. “It is futuristic to be able to control what passes through your window with your phone.”

Esfahani, Safaee and Siddiqi [Lumotune founders: Matin Esfahani, Hooman Safaee and Shafi Siddiqi] started all this as a project for their undergrad studies in 2011. They developed the technology, showcased it in March, won a lot of awards, incorporated Lumotune in April, and then collected their degrees from UW.

NanoShutters, the first commercial product to come out of Lumotune, is now in testing with a group of residential, commercial and institutional customers. The founders are using the testing to smooth out kinks and challenges in the technology and develop relationships with customers.

Safaee estimates the market for NanoShutters will be worth about $4 billion a year by 2016.

But the company was founded with much bigger ideas in mind. Instead of using their invention to make windows more or less transparent, they want the product to be used for digital displays that can be put on any surface with no visible technology.

I was not able to find any more details about how nanotechnology enables this window or, more accurately, glass ‘frosting’ experience (perhaps there’s some information in the installation guide mentioned later in this post) but the inventors do offer this video demonstrating their product,

Here’s more from the company’s homepage,

Windows drain energy and reduce privacy. NanoShutters can be fully automated to turn your window opaque or transparent according to the weather and your schedule. They can help lower heating and cooling costs by up to 20%, while always enabling privacy when you need it.

…

If you’re comfortable putting up a poster and setting up a toaster, you can install NanoShutters yourself. It takes less than 30 minutes. See how easy it is.

You can also get installation from a local NanoShutters Certified Professional.

I did click to find out if there’s a NanoShutter professional nearby but it appears there aren’t any entries yet so this may be an opportunity for entrepreneurial types.

The next two University of Waterloo startups are here courtesy of a Dec. 10, 2013 news item on DigitalJournal.com,

Harsh winter conditions may be easier for Canadians to manage with new products invented by two University of Waterloo graduates.

“Frost is a major problem for individuals and businesses daily. Not only is it inconvenient but it has an impact on safety and can even hinder economic activity,” said Abhinay Kondamreddy, a nanotechnology engineering graduate who developed Neverfrost along with three classmates.

…

For contractors who drop salt on parking lots and sidewalks, as well as the municipalities or owners who pay for it, there’s never been a way to measure how much salt is actually dispensed. Smart Scale, an automated salt logging and tracking system designed specifically for the winter maintenance industry is changing that.

The Dec. 10, 2013 University of Waterloo news release, which originated the news item, provides more detail about both Neverfrost and Smart Scale (Note: Links have been removed),

Neverfrost is an environmentally-friendly technology that prevents frost, fog, and ice formation. The innovation is the foundation for a new startup, also called Neverfrost.

By spraying Neverfrost on a windshield at night, drivers can avoid scraping and defrosting it on cold winter mornings, and clear the windshield simply by running the wipers. The Neverfrost technology prevents snow from freezing to the glass as well as fog and frost. Neverfrost expects to begin taking pre-orders for the spray with a Kickstarter campaign in March.Future plans for Neverfrost include incorporating it directly into washer fluids.

Frost and ice create challenges for aircrafts, air conditioning, commercial refrigerators, power lines, and agriculture – creating future opportunities for the Neverfrost technology.

Kondamreddy is one of two entrepreneurs who continue to further their technologies and startups thanks to a $60,000 Scientists and Engineers in Business fellowship. The fellowship is a University of Waterloo program supported by the Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario for promising entrepreneurs who want to commercialize their innovations and start high-tech businesses.

…

Developed by Raqib Omer, a Waterloo Engineering graduate, Smart Scale uses exclusive hardware wirelessly paired with GPS-enabled smart phones to track the location of a maintenance vehicle and amount of salt dispensed, and logs the information on a cloud-based system in real time. Since the cost of salt is based on size of load, property owners can be assured they’re getting what they paid for, as well as reducing risks that exist in the industry.

“With growing public concern on the environmental effects of salt, rising salt prices, and increasing fear of litigation due to slips and falls, as well as driving conditions, reliable and accurate information on salt application is becoming a necessity for maintenance contractors,” said Omer.

More than 20 winter maintenance contractors in Canada and the U.S., including Urban Meadows Property Maintenance Group in Ayr, Ontario, currently use Smart Scale.

Urban Meadows owner, William Jordan, met Omer in the early testing phase of Smart Scale and the startup phase of Omer’s company, Viaesys. As the first contractor to test Smart Scale, he quickly learned there were times his company was using too much salt.

“The accuracy rate wasn’t there at all,” said Jordan. “We’re now able to accurately monitor salt usage, prevent excessive material use, keep bullet-proof records of our work and job-cost a lot better. The real time tracking of salt has helped us use up to 30 per cent less salt.”

Smart Scale is now installed on all four of his company’s trucks which service 75 properties in Cambridge and Ayr, including parking lots for grocery stores and post offices.

Jordan, who is also chair of the snow and ice committee management sector for the horticultural trade association, Landscape Ontario, says he quickly jumped on board with Omer’s research and would like to see Smart Scale change the way salt is applied across Ontario. With no industry standards for salt application currently in place, Smart Scale could make this possible.

You can find Neverfrost and an opportunity to beta test the product here. I’ve not been able to find a website featuring Smart Scale but here’s Viaesys, a company founded by Raqib Omer, the person who developed the product. I was not able to find additional technical details for either Neverfrost or Smart Scale on either of the company websites.

* ‘Unviersity’ corrected to ‘University’ in posting header on Dec. 13, 2013. I uttered a very loud Drat! when I saw it.