A May 11, 2020 news item on ScienceDaily provides a description of the current ‘memristor scene’ along with an announcement about a piece of recent research,

Scientists around the world are intensively working on memristive devices, which are capable in extremely low power operation and behave similarly to neurons in the brain. Researchers from the Jülich Aachen Research Alliance (JARA) and the German technology group Heraeus have now discovered how to systematically control the functional behaviour of these elements. The smallest differences in material composition are found crucial: differences so small that until now experts had failed to notice them. The researchers’ design directions could help to increase variety, efficiency, selectivity and reliability for memristive technology-based applications, for example for energy-efficient, non-volatile storage devices or neuro-inspired computers.

Memristors are considered a highly promising alternative to conventional nanoelectronic elements in computer Chips [sic]. Because of the advantageous functionalities, their development is being eagerly pursued by many companies and research institutions around the world. The Japanese corporation NEC installed already the first prototypes in space satellites back in 2017. Many other leading companies such as Hewlett Packard, Intel, IBM, and Samsung are working to bring innovative types of computer and storage devices based on memristive elements to market.

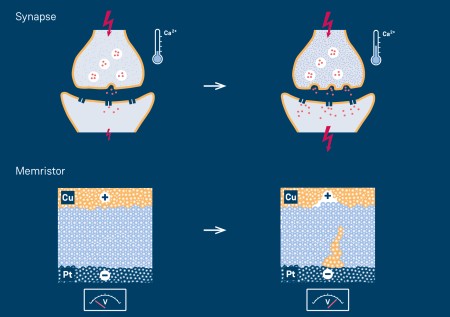

Fundamentally, memristors are simply “resistors with memory,” in which high resistance can be switched to low resistance and back again. This means in principle that the devices are adaptive, similar to a synapse in a biological nervous system. “Memristive elements are considered ideal candidates for neuro-inspired computers modelled on the brain, which are attracting a great deal of interest in connection with deep learning and artificial intelligence,” says Dr. Ilia Valov of the Peter Grünberg Institute (PGI-7) at Forschungszentrum Jülich.

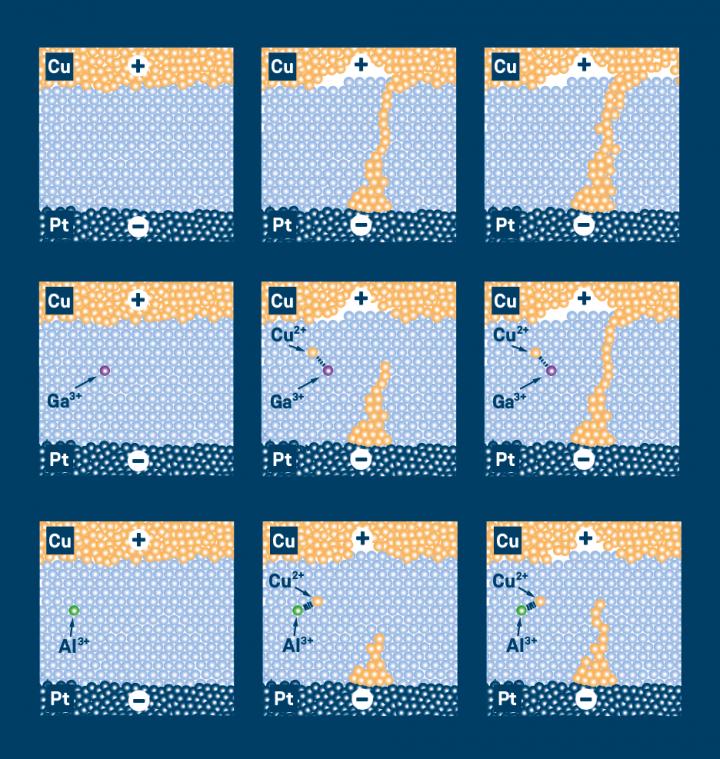

In the latest issue of the open access journal Science Advances, he and his team describe how the switching and neuromorphic behaviour of memristive elements can be selectively controlled. According to their findings, the crucial factor is the purity of the switching oxide layer. “Depending on whether you use a material that is 99.999999 % pure, and whether you introduce one foreign atom into ten million atoms of pure material or into one hundred atoms, the properties of the memristive elements vary substantially” says Valov.

A May 11, 2020 Forschungszentrum Juelich press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, delves into the theme of increasing control over memristive systems,

This effect had so far been overlooked by experts. It can be used very specifically for designing memristive systems, in a similar way to doping semiconductors in information technology. “The introduction of foreign atoms allows us to control the solubility and transport properties of the thin oxide layers,” explains Dr. Christian Neumann of the technology group Heraeus. He has been contributing his materials expertise to the project ever since the initial idea was conceived in 2015.

“In recent years there has been remarkable progress in the development and use of memristive devices, however that progress has often been achieved on a purely empirical basis,” according to Valov. Using the insights that his team has gained, manufacturers could now methodically develop memristive elements selecting the functions they need. The higher the doping concentration, the slower the resistance of the elements changes as the number of incoming voltage pulses increases and decreases, and the more stable the resistance remains. “This means that we have found a way for designing types of artificial synapses with differing excitability,” explains Valov.

Design specification for artificial synapses

The brain’s ability to learn and retain information can largely be attributed to the fact that the connections between neurons are strengthened when they are frequently used. Memristive devices, of which there are different types such as electrochemical metallization cells (ECMs) or valence change memory cells (VCMs), behave similarly. When these components are used, the conductivity increases as the number of incoming voltage pulses increases. The changes can also be reversed by applying voltage pulses of the opposite polarity.

The JARA researchers conducted their systematic experiments on ECMs, which consist of a copper electrode, a platinum electrode, and a layer of silicon dioxide between them. Thanks to the cooperation with Heraeus researchers, the JARA scientists had access to different types of silicon dioxide: one with a purity of 99.999999 % – also called 8N silicon dioxide – and others containing 100 to 10,000 ppm (parts per million) of foreign atoms. The precisely doped glass used in their experiments was specially developed and manufactured by quartz glass specialist Heraeus Conamic, which also holds the patent for the procedure. Copper and protons acted as mobile doping agents, while aluminium and gallium were used as non-volatile doping.

Record switching time confirms theory

Based on their series of experiments, the researchers were able to show that the ECMs’ switching times change as the amount of doping atoms changes. If the switching layer is made of 8N silicon dioxide, the memristive component switches in only 1.4 nanoseconds. To date, the fastest value ever measured for ECMs had been around 10 nanoseconds. By doping the oxide layer of the components with up to 10,000 ppm of foreign atoms, the switching time was prolonged into the range of milliseconds. “We can also theoretically explain our results. This is helping us to understand the physico-chemical processes on the nanoscale and apply this knowledge in the practice” says Valov. Based on generally applicable theoretical considerations, supported by experimental results, some also documented in the literature, he is convinced that the doping/impurity effect occurs and can be employed in all types memristive elements.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Design of defect-chemical properties and device performance in memristive systems by M. Lübben, F. Cüppers, J. Mohr, M. von Witzleben, U. Breuer, R. Waser, C. Neumann, and I. Valov. Science Advances 08 May 2020: Vol. 6, no. 19, eaaz9079 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz9079

This paper is open access.

For anyone curious about the German technology group, Heraeus, there’s a fascinating history in its Wikipedia entry. The technology company was formally founded in 1851 but it can be traced back to the 17th century and the founding family’s apothecary.