Professor Wei Lu (whose work on memristors has been mentioned here a few times [an April 15, 2010 posting and an April 19, 2012 posting]) has made a discovery about memristors with significant implications (from a June 25, 2014 news item on Azonano),

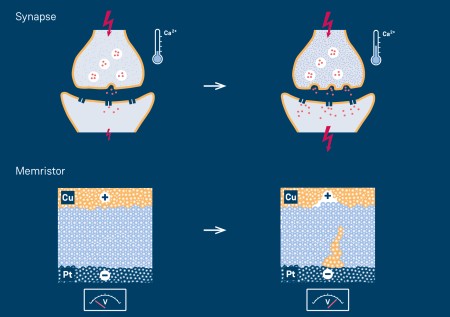

In work that unmasks some of the magic behind memristors and “resistive random access memory,” or RRAM—cutting-edge computer components that combine logic and memory functions—researchers have shown that the metal particles in memristors don’t stay put as previously thought.

The findings have broad implications for the semiconductor industry and beyond. They show, for the first time, exactly how some memristors remember.

A June 24, 2014 University of Michigan news release, which originated the news item, includes Lu’s perspective on this discovery and more details about it,

“Most people have thought you can’t move metal particles in a solid material,” said Wei Lu, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Michigan. “In a liquid and gas, it’s mobile and people understand that, but in a solid we don’t expect this behavior. This is the first time it has been shown.”

…

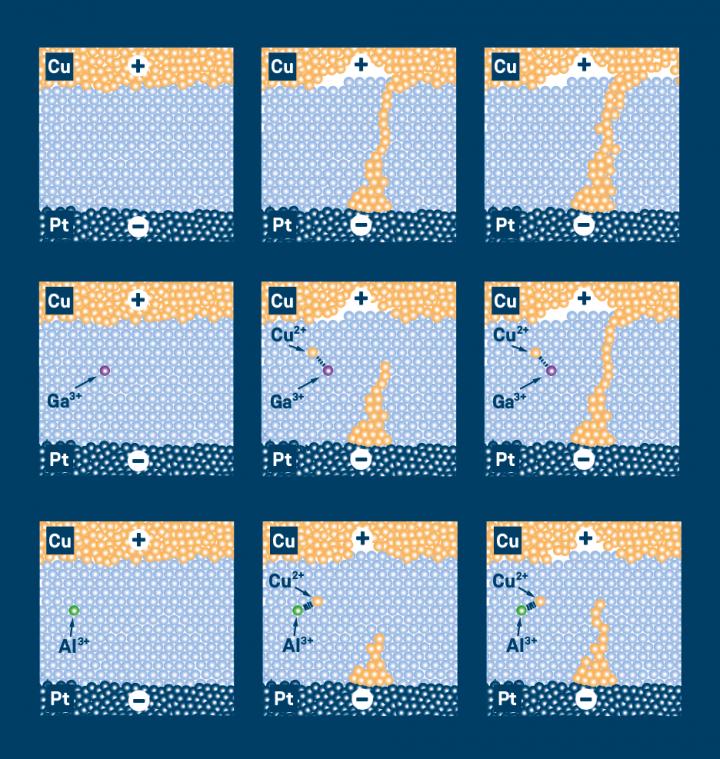

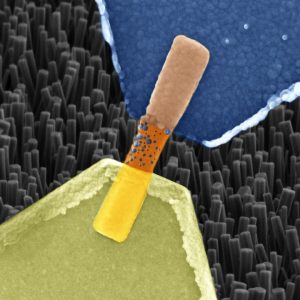

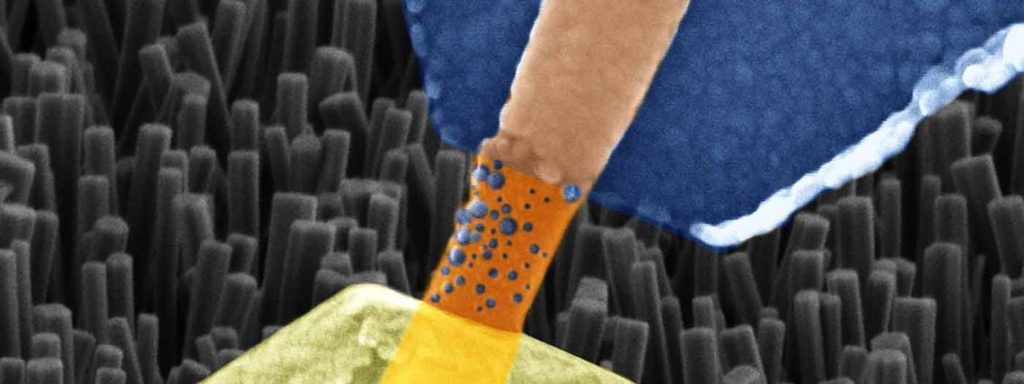

Lu, who led the project, and colleagues at U-M and the Electronic Research Centre Jülich in Germany used transmission electron microscopes to watch and record what happens to the atoms in the metal layer of their memristor when they exposed it to an electric field. The metal layer was encased in the dielectric material silicon dioxide, which is commonly used in the semiconductor industry to help route electricity.

They observed the metal atoms becoming charged ions, clustering with up to thousands of others into metal nanoparticles, and then migrating and forming a bridge between the electrodes at the opposite ends of the dielectric material.

They demonstrated this process with several metals, including silver and platinum. And depending on the materials involved and the electric current, the bridge formed in different ways.

The bridge, also called a conducting filament, stays put after the electrical power is turned off in the device. So when researchers turn the power back on, the bridge is there as a smooth pathway for current to travel along. Further, the electric field can be used to change the shape and size of the filament, or break the filament altogether, which in turn regulates the resistance of the device, or how easy current can flow through it.

Computers built with memristors would encode information in these different resistance values, which is in turn based on a different arrangement of conducting filaments.

Memristor researchers like Lu and his colleagues had theorized that the metal atoms in memristors moved, but previous results had yielded different shaped filaments and so they thought they hadn’t nailed down the underlying process.

“We succeeded in resolving the puzzle of apparently contradicting observations and in offering a predictive model accounting for materials and conditions,” said Ilia Valov, principle investigator at the Electronic Materials Research Centre Jülich. “Also the fact that we observed particle movement driven by electrochemical forces within dielectric matrix is in itself a sensation.”

The implications for this work (from the news release),

The results could lead to a new approach to chip design—one that involves using fine-tuned electrical signals to lay out integrated circuits after they’re fabricated. And it could also advance memristor technology, which promises smaller, faster, cheaper chips and computers inspired by biological brains in that they could perform many tasks at the same time.

As is becoming more common these days (from the news release),

Lu is a co-founder of Crossbar Inc., a Santa Clara, Calif.-based startup working to commercialize RRAM. Crossbar has just completed a $25 million Series C funding round.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Electrochemical dynamics of nanoscale metallic inclusions in dielectrics by Yuchao Yang, Peng Gao, Linze Li, Xiaoqing Pan, Stefan Tappertzhofen, ShinHyun Choi, Rainer Waser, Ilia Valov, & Wei D. Lu. Nature Communications 5, Article number: 4232 doi:10.1038/ncomms5232 Published 23 June 2014

This paper is behind a paywall.

The other party instrumental in the development and, they hope, the commercialization of memristors is HP (Hewlett Packard) Laboratories (HP Labs). Anyone familiar with this blog will likely know I have frequently covered the topic starting with an essay explaining the basics on my Nanotech Mysteries wiki (or you can check this more extensive and more recently updated entry on Wikipedia) and with subsequent entries here over the years. The most recent entry is a Jan. 9, 2014 posting which featured the then latest information on the HP Labs memristor situation (scroll down about 50% of the way). This new information is more in the nature of a new revelation of details rather than an update on its status. Sebastian Anthony’s June 11, 2014 article for extremetech.com lays out the situation plainly (Note: Links have been removed),

HP, one of the original 800lb Silicon Valley gorillas that has seen much happier days, is staking everything on a brand new computer architecture that it calls… The Machine. Judging by an early report from Bloomberg Businessweek, up to 75% of HP’s once fairly illustrious R&D division — HP Labs – are working on The Machine. As you would expect, details of what will actually make The Machine a unique proposition are hard to come by, but it sounds like HP’s groundbreaking work on memristors (pictured top) and silicon photonics will play a key role.

…

First things first, we’re probably not talking about a consumer computing architecture here, though it’s possible that technologies commercialized by The Machine will percolate down to desktops and laptops. Basically, HP used to be a huge player in the workstation and server markets, with its own operating system and hardware architecture, much like Sun. Over the last 10 years though, Intel’s x86 architecture has rapidly taken over, to the point where HP (and Dell and IBM) are essentially just OEM resellers of commodity x86 servers. This has driven down enterprise profit margins — and when combined with its huge stake in the diminishing PC market, you can see why HP is rather nervous about the future. The Machine, and IBM’s OpenPower initiative, are both attempts to get out from underneath Intel’s x86 monopoly.

…

While exact details are hard to come by, it seems The Machine is predicated on the idea that current RAM, storage, and interconnect technology can’t keep up with modern Big Data processing requirements. HP is working on two technologies that could solve both problems: Memristors could replace RAM and long-term flash storage, and silicon photonics could provide faster on- and off-motherboard buses. Memristors essentially combine the benefits of DRAM and flash storage in a single, hyper-fast, super-dense package. Silicon photonics is all about reducing optical transmission and reception to a scale that can be integrated into silicon chips (moving from electrical to optical would allow for much higher data rates and lower power consumption). Both technologies can be built using conventional fabrication techniques.

In a June 11, 2014 article by Ashlee Vance for Bloomberg Business Newsweek, the company’s CTO (Chief Technical Officer), Martin Fink provides new details,

That’s what they’re calling it at HP Labs: “the Machine.” It’s basically a brand-new type of computer architecture that HP’s engineers say will serve as a replacement for today’s designs, with a new operating system, a different type of memory, and superfast data transfer. The company says it will bring the Machine to market within the next few years or fall on its face trying. “We think we have no choice,” says Martin Fink, the chief technology officer and head of HP Labs, who is expected to unveil HP’s plans at a conference Wednesday [June 11, 2014].

In my Jan. 9, 2014 posting there’s a quote from Martin Fink stating that 2018 would be earliest date for the company’s StoreServ arrays to be packed with 100TB Memristor drives (the Machine?). The company later clarified the comment by noting that it’s very difficult to set dates for new technology arrivals.

Vance shares what could be a stirring ‘origins’ story of sorts, provided the Machine is successful,

The Machine started to take shape two years ago, after Fink was named director of HP Labs. Assessing the company’s projects, he says, made it clear that HP was developing the needed components to create a better computing system. Among its research projects: a new form of memory known as memristors; and silicon photonics, the transfer of data inside a computer using light instead of copper wires. And its researchers have worked on operating systems including Windows, Linux, HP-UX, Tru64, and NonStop.

Fink and his colleagues decided to pitch HP Chief Executive Officer Meg Whitman on the idea of assembling all this technology to form the Machine. During a two-hour presentation held a year and a half ago, they laid out how the computer might work, its benefits, and the expectation that about 75 percent of HP Labs personnel would be dedicated to this one project. “At the end, Meg turned to [Chief Financial Officer] Cathie Lesjak and said, ‘Find them more money,’” says John Sontag, the vice president of systems research at HP, who attended the meeting and is in charge of bringing the Machine to life. “People in Labs see this as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Here is the memristor making an appearance in Vance’s article,

HP’s bet is the memristor, a nanoscale chip that Labs researchers must build and handle in full anticontamination clean-room suits. At the simplest level, the memristor consists of a grid of wires with a stack of thin layers of materials such as tantalum oxide at each intersection. When a current is applied to the wires, the materials’ resistance is altered, and this state can hold after the current is removed. At that point, the device is essentially remembering 1s or 0s depending on which state it is in, multiplying its storage capacity. HP can build these chips with traditional semiconductor equipment and expects to be able to pack unprecedented amounts of memory—enough to store huge databases of pictures, files, and data—into a computer.

…

New memory and networking technology requires a new operating system. Most applications written in the past 50 years have been taught to wait for data, assuming that the memory systems feeding the main computers chips are slow. Fink has assigned one team to develop the open-source Machine OS, which will assume the availability of a high-speed, constant memory store. …

Peter Bright in his June 11, 2014 article for Ars Technica opens his article with a controversial statement (Note: Links have been removed),

In 2008, scientists at HP invented a fourth fundamental component to join the resistor, capacitor, and inductor: the memristor. [emphasis mine] Theorized back in 1971, memristors showed promise in computing as they can be used to both build logic gates, the building blocks of processors, and also act as long-term storage.

Whether or not the memristor is a fourth fundamental component has been a matter of some debate as you can see in this Memristor entry (section on Memristor definition and criticism) on Wikipedia.

Bright goes on to provide a 2016 delivery date for some type of memristor-based product and additional technical insight about the Machine,

… By 2016, the company plans to have memristor-based DIMMs, which will combine the high storage densities of hard disks with the high performance of traditional DRAM.

John Sontag, vice president of HP Systems Research, said that The Machine would use “electrons for processing, photons for communication, and ions for storage.” The electrons are found in conventional silicon processors, and the ions are found in the memristors. The photons are because the company wants to use optical interconnects in the system, built using silicon photonics technology. With silicon photonics, photons are generated on, and travel through, “circuits” etched onto silicon chips, enabling conventional chip manufacturing to construct optical parts. This allows the parts of the system using photons to be tightly integrated with the parts using electrons.

The memristor story has proved to be even more fascinating than I thought in 2008 and I was already as fascinated as could be, or so I thought.