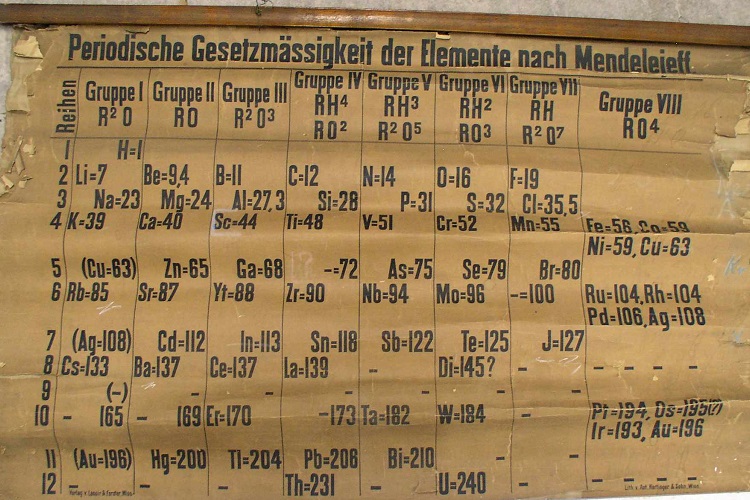

The University of St. Andrews kicked off the new year (2019) by announcing the discovery of what’s believed to the world’s oldest periodic table chart. From a January 17, 2019 news item on phys.org

A periodic table chart discovered at the University of St Andrews is thought to be the oldest in the world.

The chart of elements, dating from 1885, was discovered in the University’s School of Chemistry in 2014 by Dr. Alan Aitken during a clear out. The storage area was full of chemicals, equipment and laboratory paraphernalia that had accumulated since the opening of the chemistry department at its current location in 1968. Following months of clearing and sorting the various materials a stash of rolled up teaching charts was discovered. Within the collection was a large, extremely fragile periodic table that flaked upon handling. Suggestions that the discovery may be the earliest surviving example of a classroom periodic table in the world meant the document required urgent attention to be authenticated, repaired and restored.

A January 17, 2019 University of St. Andrews press release, which originated the news item, describes the chart and future plans for it in more detail,

Mendeleev made his famous disclosure on periodicity in 1869, the newly unearthed table was rather similar, but not identical to Mendeleev’s second table of 1871. However, the St Andrews table was clearly an early specimen. The table is annotated in German, and an inscription at the bottom left – ‘Verlag v. Lenoir & Forster, Wien’ – identifies a scientific printer who operated in Vienna between 1875 and 1888. Another inscription – ‘Lith. von Ant. Hartinger & Sohn, Wien’ – identifies the chart’s lithographer, who died in 1890. Working with the University’s Special Collections team, the University sought advice from a series of international experts. Following further investigations, no earlier lecture chart of the table appears to exist. Professor Eric Scerri, an expert on the history of the periodic table based at the University of California, Los Angeles, dated the table to between 1879 and 1886 based on the represented elements. For example, both gallium and scandium, discovered in 1875 and 1879 respectively, are present, while germanium, discovered in 1886, is not.

In view of the table’s age and emerging uniqueness it was important for the teaching chart to be preserved for future generations. The paper support of the chart was fragile and brittle, its rolled format and heavy linen backing contributed to its poor mechanical condition. To make the chart safe for access and use it received a full conservation treatment. The University’s Special Collections was awarded a funding grant from the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust (NMCT) for the conservation of the chart in collaboration with private conservator Richard Hawkes (Artworks Conservation). Treatment to the chart included: brushing to remove loose surface dirt and debris, separating the chart from its heavy linen backing, washing the chart in de-ionised water adjusted to a neutral pH with calcium hydroxide to remove the soluble discolouration and some of the acidity, a ‘de-acidification’ treatment by immersion in a bath of magnesium hydrogen carbonate to deposit an alkaline reserve in the paper, and finally repairing tears and losses using a Japanese kozo paper and wheat starch paste. The funding also allowed production of a full-size facsimile which is now on display in the School of Chemistry. The original periodic table has been rehoused in conservation grade material and is stored in Special Collections’ climate-controlled stores in the University.

A researcher at the University, M Pilar Gil from Special Collections, found an entry in the financial transaction records in the St Andrews archives recording the purchase of an 1885 table by Thomas Purdie from the German catalogue of C Gerhardt (Bonn) for the sum of 3 Marks in October 1888. This was paid from the Class Account and included in the Chemistry Class Expenses for the session 1888-1889. This entry and evidence of purchase by mail order appears to define the provenance of the St Andrews periodic table. It was produced in Vienna in 1885 and was purchased by Purdie in 1888. Purdie was professor of Chemistry from 1884 until his retirement in 1909. This in itself is not so remarkable, a new professor setting up in a new position would want the latest research and teaching materials. Purdie’s appointment was a step-change in experimental research at St Andrews. The previous incumbents had been mineralogists, whereas Purdie had been influenced by the substantial growth that was taking place in organic chemistry at that time. What is remarkable however is that this table appears to be the only surviving one from this period across Europe. The University is keen to know if there are others out there that are close in age or even predate the St Andrews table.

Professor David O’Hagan, recent ex-Head of Chemistry at the University of St Andrews, said: “The discovery of the world’s oldest classroom periodic table at the University of St Andrews is remarkable. The table will be available for research and display at the University and we have a number of events planned in 2019, which has been designated international year of the periodic table by the United Nations, to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the table’s creation by Dmitri Mendeleev.”

Gabriel Sewell, Head of Special Collections, University of St Andrews, added: “We are delighted that we now know when the oldest known periodic table chart came to St Andrews to be used in teaching. Thanks to the generosity of the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust, the table has been preserved for current and future generations to enjoy and we look forward to making it accessible to all.”

They’ve timed their announcement very well since it’s UNESCO’s (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) 2019 International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements (IYPT2019). My January 8, 2019 posting offers more information and links about the upcoming festivities. By the way, this year is also the table’s 150th anniversary.

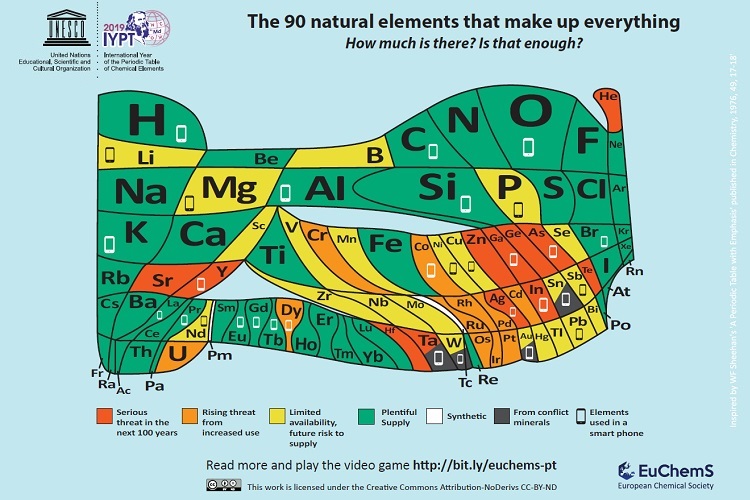

Getting back to Scotland, scientists there have created a special Periodic Table of Elements charting ‘element scarcity’, according to a January 22, 2019 University of St. Andrews press release,

Scientists from the University of St Andrews have developed a unique periodic table which highlights the scarcity of elements used in everyday devices such as smart phones and TVs.

Chemical elements which make up mobile phones are included on an ‘endangered list’ in the landmark version of the periodic table to mark its 150th anniversary. Around ten million smartphones are discarded or replaced every month in the European Union alone. The European Chemical Society (EuChemS), which represents more than 160,000 chemists, has developed the unique periodic table to highlight both the remaining availability of all 90 elements and their vulnerability.

The unique updated periodic table will be launched at the European Parliament today (Tuesday 22 January), by British MEPs Catherine Stihler and Clare Moody. The event will also highlight the recent discovery of the oldest known wallchart of the Periodic Table, discovered last year at the University of St Andrews.

Smartphones are made up of around 30 elements, over half of which give cause for concern in the years to come because of increasing scarcity – whether because of limited supplies, their location in conflict areas, or our incapacity to fully recycle them.

With finite resources being used up so fast, EuChemS Vice-President and Emeritus Professor in Chemistry at the University of St Andrews, Professor David Cole-Hamilton, has questioned the trend for replacing mobile phones every two years, urging users to recycle old phones correctly. EuChemS wants a greater recognition of the risk to the lifespan of elements, and the need to support better recycling practices and a true circular economy.

Professor David Cole-Hamilton said: “It is astonishing that everything in the world is made from just 90 building blocks, the 90 naturally occurring chemical elements.

“There is a finite amount of each and we are using some so fast that they will be dissipated around the world in less than 100 years.

“Many of these elements are endangered, so should you really change your phone every two years?”

Catherine Stihler, Labour MEP for Scotland and former Rector of the University of St Andrews, said: “As we mark the 150th anniversary of the periodic table, it’s fascinating to see it updated for the 21st century.

“But it’s also deeply worrying to see how many elements are on the endangered list, including those which make up mobile phones.

“It is a lesson to us all to care for the world around us, as these naturally-occurring elements won’t last forever unless we increase global recycling rates and governments introduce a genuine circular economy.”

Pilar Goya, EuChemS President, said: “For EuChemS, the supranational organisation representing more than 160,000 chemists from different European countries, the celebration of the International Year of the Periodic Table is a great opportunity to communicate the crucial role of chemistry in overcoming the challenges society will be facing in the near future.”

The new Periodic Table can be viewed online.‘The Periodic Table and us: its history, meaning and element scarcity’ takes place at The European Parliament, Brussels, Belgium on 22 January 2019. The two-hour session features speakers from the chemical sciences as well as representatives from the European Parliament and the European Commission.

This year (2019) is the United Nations International Year of the Periodic Table (IYPT2019) and the 150th anniversary of scientist Dmitri Mendeleev’s discovery of the periodic system as we now know it. Natalia Tarasova, Past-President of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), will present the IYPT2019.

The Periodic Table of chemical elements is one of the most significant scientific achievements and is today one of the best-known symbols of science, recognised and studied by people around the globe.

EuChemS, the European Chemical Society, coordinates the work of 48 chemical societies and other chemistry related organisations, representing more than 160,000 chemists. Through the promotion of chemistry and by providing expert and scientific advice, EuChemS aims to take part in solving today’s major societal challenges.

Here’s what the ‘new’ periodic table looks like: