It seems a little early to be talking about 6G technology, given that in Canada 5G technology is not fully implemented (from a February 8, 2021 article [unchanged as November 18, 2021] by Stephen Clark for whistleout.ca), Note: A link has been removed,

Should I Buy a 5G Phone Now?

There is no rush to buy a 5G phone for most Canadians. Current 5G smartphones offer other premium features such as leading edge Qualcomm CPU performance, brilliant OLED screens and recording video at 8K resolution. These devices can also cost well over $1,000, so you don’t shop for a 5G phone if that’s the only premium feature you are looking for. We expect that Canadians won’t see coast-to-coast coverage by 5G cell towers until at least 2022 [emphasis mine]. Besides, Canada’s 4G LTE mobile performance is among the fastest in the world, serves 99% of Canadians and 4G smartphones will continue to be supported for many years.

A study released by OpenSignal found Canadian 5G networks among the top 5 best in the world for mobile gaming. …

It’s good not to get too focused on one’s naval as there are many other countries in the world and it’s likely at least some, if not most, are more advanced with their 5G technology deployment and are looking forward to 6G. (See this November 1, 2021 University of Tokyo news release “Japan and Finland collaborate to develop 6G” on EurekAlert.)

Now to 6G news, this June 28, 2021 news item on phys.org describes a new technique for producing the new materials necessary for a future 6G deployment,

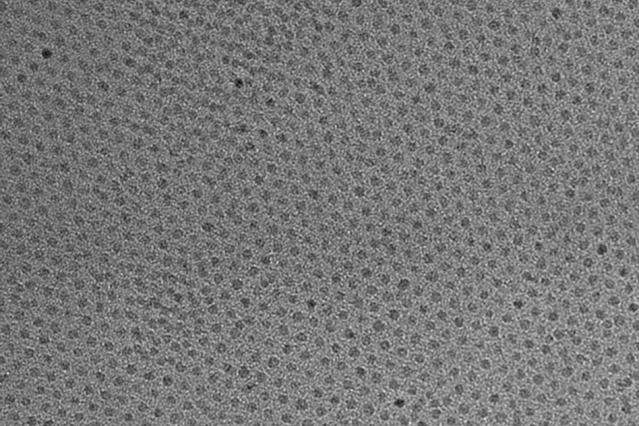

Material scientists have developed a fast method for producing epsilon iron oxide and demonstrated its promise for next-generation communications devices. Its outstanding magnetic properties make it one of the most coveted materials, such as for the upcoming 6G generation of communication devices and for durable magnetic recording. The work was published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry C, a journal of the Royal Society of Chemistry.

A June 23, 2021 Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT) press release, which originated the news item, describes the work in detail,

Iron oxide (III) is one of the most widespread oxides on Earth. It is mostly found as the mineral hematite (or alpha iron oxide, α-Fe2O3). Another stable and common modification is maghemite (or gamma modification, γ-Fe2O3). The former is widely used in industry as a red pigment, and the latter as a magnetic recording medium. The two modifications differ not only in crystalline structure ( alpha-iron oxide has hexagonal syngony and gamma-iron oxide has cubic syngony) but also in magnetic properties.

In addition to these forms of iron oxide (III), there are more exotic modifications such as epsilon-, beta-, zeta-, and even glassy. The most attractive phase is epsilon iron oxide, ε-Fe2O3. This modification has an extremely high coercive force (the ability of the material to resist an external magnetic field). The strength reaches 20 kOe at room temperature, which is comparable to the parameters of magnets based on expensive rare-earth elements. Furthermore, the material absorbs electromagnetic radiation in the sub-terahertz frequency range (100-300 GHz) through the effect of natural ferromagnetic resonance.The frequency of such resonance is one of the criteria for the use of materials in wireless communications devices – the 4G standard uses megahertz and 5G uses tens of gigahertz. There are plans to use the sub-terahertz range as a working range in the sixth generation (6G) wireless technology, which is being prepared for active introduction in our lives from the early 2030s.

The resulting material is suitable for the production of converting units or absorber circuits at these frequencies. For example, by using composite ε-Fe2O3 nanopowders it will be possible to make paints that absorb electromagnetic waves and thus shield rooms from extraneous signals, and protect signals from interception from the outside. The ε-Fe2O3 itself can also be used in 6G reception devices.

Epsilon iron oxide is an extremely rare and difficult form of iron oxide to obtain. Today, it is produced in very small quantities, with the process itself taking up to a month. This, of course, rules out its widespread application. The authors of the study developed a method for accelerated synthesis of epsilon iron oxide capable of reducing the synthesis time to one day (that is, to carry out a full cycle of more than 30 times faster!) and increasing the quantity of the resulting product. The technique is simple to reproduce, cheap and can be easily implemented in industry, and the materials required for the synthesis – iron and silicon – are among the most abundant elements on Earth.

“Although the epsilon-iron oxide phase was obtained in pure form relatively long ago, in 2004, it still has not found industrial application due to the complexity of its synthesis, for example as a medium for magnetic – recording. We have managed to simplify the technology considerably,” says Evgeny Gorbachev, a PhD student in the Department of Materials Sciences at Moscow State University and the first author of the work.

The key to successful application of materials with record-breaking characteristics is research into their fundamental physical properties. Without in-depth study, the material may be undeservedly forgotten for many years, as has happened more than once in the history of science. It was the tandem of materials scientists at Moscow State University, who synthesised the compound, and physicists at MIPT, who studied it in detail, that made the development a success.

“Materials with such high ferromagnetic resonance frequencies have enormous potential for practical applications. Today, terahertz technology is booming: it is the Internet of Things, it is ultra-fast communications, it is more narrowly focused scientific devices, and it is next-generation medical technology. While the 5G standard, which was very popular last year, operates at frequencies in the tens of gigahertz, our materials are opening the door to significantly higher frequencies (hundreds of gigahertz), which means that we are already dealing with 6G standards and higher. Now it’s up to engineers, we are happy to share the information with them and look forward to being able to hold a 6G phone in our hands,” says Dr. Liudmila Alyabyeva, Ph.D., senior researcher at the MIPT Laboratory of Terahertz Spectroscopy , where the terahertz research was carried out.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Tuning the particle size, natural ferromagnetic resonance frequency and magnetic properties of ε-Fe2O3 nanoparticles prepared by a rapid sol–gel method by Evgeny Gorbachev, Miroslav Soshnikov, Mingxi Wu, Liudmila Alyabyeva, Dmitrii Myakishev, Ekaterina Kozlyakova, Vasilii Lebedev, Evgeny Anokhin, Boris Gorshunov, Oleg Brylev, Pavel Kazin, Lev Truso. J. Mater. Chem. C, 2021,9, 6173-6179 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1039/D1TC01242H First published 26 Apr 2021

This paper is behind a paywall.