Be careful not to fall, is a familiar stricture when applied to ‘leaning out of windows’ supplying a frisson of danger to the ‘lean’ but in German, ‘aus dem Fenster lehnen’ or ‘lean out of the window’, is an expression for interdisciplinarity. It’s a nice touch for a book about an art/physics collaboration where it can feel ‘dangerous’ to move so far out of your comfort zone. The book is described this way in its Vancouver (Canada) Public Library catalogue entry,

Art and physics collide in this expansive exploration of how knowledge can be translated across disciplinary communities to activate new aesthetic and scientific perspectives.

Leaning Out of Windows shares findings from a six-year collaboration by a group of artists and physicists exploring the connections and differences between the language they use [emphasis mine], the means by which they develop knowledge, how that knowledge is visualized, and, ultimately, how they seek to understand the universe. Physicists from TRIUMF, Canada’s particle physics accelerator, presented key concepts in the physics of Antimatter, Emergence, and In/visible Forces to artists convened by Emily Carr University of Art + Design; the participants then generated conversations, process drawings, diagrams, field notes, and works of art. The “wondrous back-and-forth” of this process allowed both scientists and artists to, as Koenig [Ingrid Koenig] and Cutler [Randy Lee Cutler] describe, “lean out of our respective fields of inquiry and inhabit the infinite spaces of not knowing.”

From this leaning into uncertainty comes a rich array of work towards furthering the shared project of artists and scientists in shaping cultural understandings of the universe: Otoniya J. Okot Bitek reflects on the invisible forces of power; Jess H. Brewer contemplates emergence, free will, and magic; Mimi Gellman looks at the resonances between Indigenous Knowledge and physics; Jeff Derksen finds Hegelian dialectics within the matter-antimatter process; Sanem Güvenç considers the possibilities of the void; Nirmal Raj ponders the universe’s “special moment of light and visibility” we happen to inhabit; Sadira Rodrigues eschews the artificiality of the lab for a “boring berm of dirt”; and Marina Roy metaphorically turns beams of stable and radioactive gold particles into art of pigments, oils, liquid plastic, and wood. Combined with additional essays, diagrams, and artworks, these texts and artworks live in the intersection of disparate fields that nonetheless share a deep curiosity of the world and our place within it, and a dedication to building and sharing knowledges.

Self-published, “Leaning Out of Windows: An Art and Physics Collaboration” and edited by Ingrid Koenig & Randy Lee Cutler (who also wrote many of the essays) was produced through an entity known as Figure 1 (located in Vancouver). It can be purchased for $45 CAD here on the Figure 1 website or $41.71 (CAD?) on Amazon. (Weirdly, if you look at the back outside cover you’ll see a price of $45 USD.)

Kind of a book

“Leaning” functions as three kinds of books in one package. First, it is documentation for a six year project funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), second, a collection of essays, and, third, a catalogue for three inter-related exhibitions. (Aside: my focus is primarily on the text for an informal book review.)

Like an art exhibition catalogue, this book is printed in a large, awkward to hold format, with shiny (coated) pages. It makes reading the essays and documentation a little challenging but perfect for a picture book/coffee table book where the images are supposed to look good.

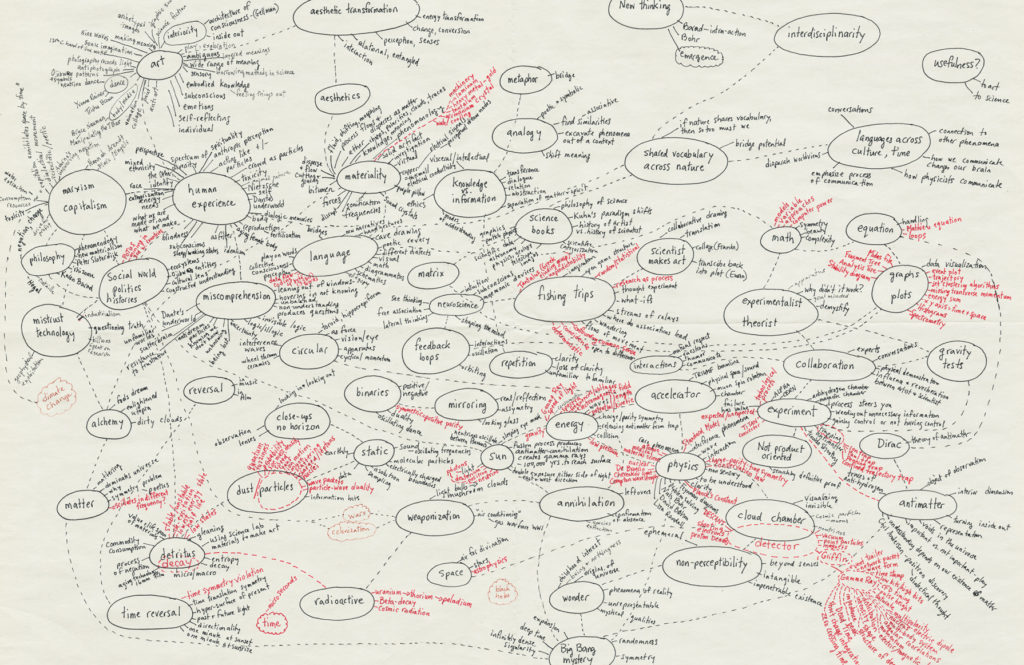

I particularly liked the maps for the various phases of the project and the images for phase 1 showing what happens when an image is passed from one artist to the next, without explanation, asking for a new image to be produced and passed on to yet another artist and so on. There is no discussion amongst the artists about the initial impetus (the first artist in the stream of four met with physicists at a science symposium to talk about antimatter).

Unexpectedly, the documentation proved to be a highlight for me. BTW, you can find out more about the Leaning Out of Windows (LOoW) project (e.g. participants, phases, and art/science resources) on its website.

Koenig should be congratulated for getting as much publicity for the book as possible, given the topic and that there are no celebrities involved. CBC gave it a mention (May 8, 2023) on its Books: Leaning Out of Windows webpage. It also got a mention by Dana Gee in a May 12, 2023 ‘Books brief‘ posting on the Vancouver Sun website.

Plus, there were a couple of articles in an art magazine highlighting the art/science project while it was in progress featuring the few images I was about to access online for this project.

A January 6, 2020 article in Canadian Art Magazine by Randy Lee Cutler and Ingrid Koenig introduces the project (Note: I’ll revisit the “metaphor and analogy” mention in this article and throughout the LOoW book later in this post),

The disciplines of art and physics share certain critical perspectives: both deal with how metaphor and analogy inform creative processes. Additionally, artists and physicists address issues of the imagination, creative thinking and communication, and how meaning is made through theoretical research and process-based investigations. There are also important differences in these perspectives. Art brings an appreciation for abstract or non-representational practices. Physics research addresses complex problems relevant to understanding the study of matter and motion through space and time. Physicists also contribute knowledge about how the universe behaves. Together, the achievements of art and physics allow the possibility of a much richer understanding of the nature of reality than each field can contribute individually.

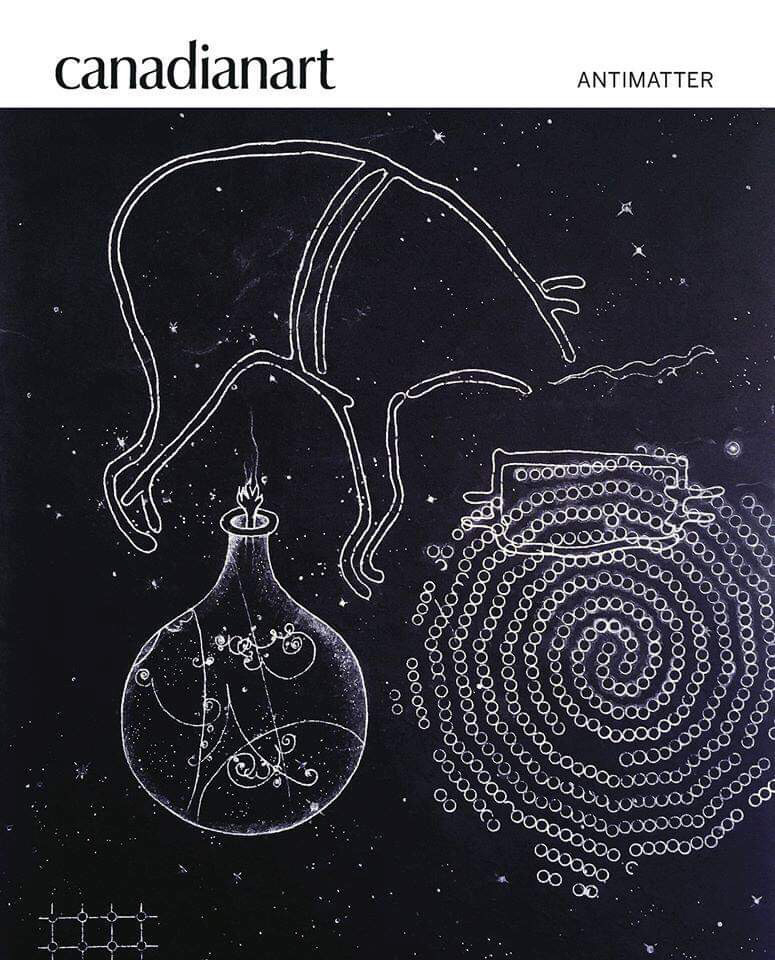

There’s a January 13, 2020 article in Canadian Art Magazine by Perrin Grauer featuring Mimi Gellman, Note: A link has been removed,

Artwork by artist and ECU Associate Professor Mimi Gellman was selected to appear on the cover of the current issue of Canadian Art magazine.

The gleaming, otherworldly image graces the magazine’s issue on antimatter —a subject which “presents a mirror world of abstract phenomena: time reversals, mutual annihilation, cosmic rays, cloud chambers, an infinite sea of sub-atomic particles that parallels our ‘real’ world of matter,” according to the issue’s editors.

Mimi describes her work as approaching some of the affinities between the biological, the perceptual, the cultural and the astronomical.

“My drawings do not explore the exterior world we perceive but rather what I call the ‘architecture of consciousness’ which permits us to perceive it,” she says.

“Recalling astronomical diagrams and reflecting the mixture of hybrid cultural worldviews in my background, they reveal deep similarities between the dimension explored by sub-atomic physics and the implicit interiority of contemporary art.”

…

I’m sorry I never saw any announcements for the project exhibitions, all of which seemed to have taken place at the Emily Carr University of Art + Design. There were three concepts each explored in three exhibitions, with different artists each time, titled: Antimatter, Emergence, and In/visible Forces, respectively.

A bouquet or two and a few nitpicks

Randy Lee Cutler and Ingrid Koenig have a wonderful quote from Karen Barad, physicist and philosopher, in their essay titled, “Collaborative Research between Artists and Physicists,”

Barad introduces the concept of intra-action and the fluidity of materialization through our bodily entanglements—through intra-action our bodies remain entangled with those around us. “Not only subjects but also objects are permeated through and through with their entangled kin, the other is not just in one’s skin, but in one’s bones, in one’s belly in one’s heart, in one’s nucleus, in one’s past and future.This is a true for electrons as it is for brittlestars as it is for the differentially constituted human.” As Barad asks herself, “How do I know where my physics begins and ends?” … [p. 13]

To the left of the page is a black and white photograph of entangled cables captioned, “GRIFFIN (Gamma Ray Infrastructure for Fundamental Investigations of Nuclei- TRIUMF.” It’s a nice touch and points to the difficulty of ‘illustrating’ or producing visual art in response to physics ideas such as quantum entanglement, something Einstein called, ‘spooky action at a distance’. From the Quantum entanglement Wikipedia entry, Note: Links have been removed,

Quantum entanglement is the phenomenon that occurs when a group of particles are generated, interact, or share spatial proximity in a way such that the quantum state of each particle of the group cannot be described independently of the state of the others [[emphasis mine], including when the particles are separated by a large distance [emphasis mine]. The topic of quantum entanglement is at the heart of the disparity between classical and quantum physics: entanglement is a primary feature of quantum mechanics not present in classical mechanics.[1]

Some of the essays

One essay that stood out in LOoW, was “A Boring Berm of Dirt’ (pp. 141-7) by Sadira Rodrigues. She notes that dirt and soil are not the same; one is dead (dirt) and the other is living (soil) and that the berm has an important role at TRIUMF. If you want a more specific discussion of the difference between dirt and soil, see David Beaulieu’s February 23, 2023 essay (Soil vs. Dirt: What’s the Difference?) on The Spruce website.

Rodrigues’ essay (part of the Emergence concept) situates the work physically (word play alert: physics/physically) whereas all of the other work is based on ideas.

In “Boring Berm … ,” radioactivity is mentioned, a term which is largely taboo these days due its association with poisoning, bombs, and death. The eassy goes into fascinating detail about TRIUMF’s underground facility and how the facility deals with its nuclear waste and the role that the berm plays. (On a more fanciful note, the danger in the title of the book is given another dimension in this essay focused on nuclear topics.) Regardless, the essay was definitely an eye-opener.

Aside: The institution has been rebranded from: TRIUMF (Canada’s National Laboratory for Particle and Nuclear Physics) to: TRIUMF (Canada’s national particle accelerator centre). You can find a reference to the ‘nuclear’ name in my October 2, 2018 posting although the name was already changed, probably in the early to mid-2010s. There is no mention of the ‘nuclear’ name in TRIUMF’s Wikipedia entry, accessed August 22, 2023.

Gellman and language

Mimi Gellman’s essay, “Crossing No Divide: Mapping Affinities in Art and Science” evokes unity, as can be seen in the title. She’s one of the more ‘lyrical’ writers,

There is a place in our imagination where east or west, or large or small, or any other opposites cease to be productive contradictions. As an artist and educator, I have become interested in the non-binary and resonance between Indigenous Knowledge and physics, between art and science, and between traditional ways of considering cognition and thinking with the hand. [p. 33]

This is how Gellman is described for the January 13, 2020 article in Canadian Art Magazine, which is archived on the Emily Carr University of Art + Design (ECUAD) website,

Mimi Gellman is an Anishinaabe/Ashkenazi (Ojibway-Jewish Métis) visual artist and educator with a multi-streamed practice in architectural glass and conceptual installation. She is currently an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Culture + Community at Emily Carr University of Art + Design in Vancouver, Canada, and is completing her research praxis PhD in Cultural Studies at Queen’s University on the metaphysics of Indigenous mapping.

…

She highlights some interesting observations about language and thinking,

The Ojibwe language, Anishinaabemowin, like many Indigenous languages is verb-based in contrast with Western languages’ noun-based constructions and these have deep implications for the development of one’s worldview. …

I suspect anyone who speaks more than one language can testify to the observation that language affects one’s worldview. More academically, it’s called linguistic relativity or the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. I find it hard to believe that it’s considered a controversial idea but here goes from the Linguistic relativity Wikipedia entry, Note: Links have been removed,

The idea of linguistic relativity, also known as the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis /səˌpɪər ˈhwɔːrf/ sə-PEER WHORF, the Whorf hypothesis, or Whorfianism, is a principle suggesting that the structure of a language influences its speakers’ worldview or cognition, and thus individuals’ languages determine or shape their perceptions of the world.[1]

The hypothesis has long been controversial, and many different, often contradictory variations have existed throughout its history.[2] The strong hypothesis of linguistic relativity, now referred to as linguistic determinism, says that language determines thought and that linguistic categories limit and restrict cognitive categories. This was held by some of the early linguists before World War II,[3] but it is generally agreed to be false by modern linguists.[4] Nevertheless, research has produced positive empirical evidence supporting a weaker version of linguistic relativity:[4][3] that a language’s structures influence and shape a speaker’s perceptions, without strictly limiting or obstructing them.

…

Gettng back to Gellman, language, linguistic relativity, worldviews, and, adding physics/science, she quotes James (Sa’ke’j) Youngblood Henderson “a research fellow at the Native Law Centre of Canada, University of Saskatchewan College of Law. He was born to the Bear Clan of the Chickasaw Nation and Cheyenne Tribe in Oklahoma in 1944 and is married to Marie Battiste, a Mi’kmaw educator. In 1974, he received a juris doctorate in law from Harvard Law School,”

[at a 1993 dialogue between Western and Indigenous scientists …]

[Youngblood Henderson] We don’t have one god. You need a noun-based language to have one god. We have forces. All forces are equal and you are just the amplifier of the forces. The way you conduct your life and the dignity you give to other things gives you access to other forces. Even trees are verbs instead of nouns. The Mi’kmaq named their trees for the sound the wind makes when it blows through the trees during the autumn about an hour after the sunset, when the wind usually comes from a certain direction. So one might be like a ‘shu-shu’ something and another more like a ‘tinka-tinka’ something. Although physics in the western world has been essentially the quest for the smallest noun (which used to be a-tom, ‘that which cannot be further divided’), as they were inside the atom things weren’t acting like nouns anymore. The physicists were intrigued with the possibilities inherent in a language that didn’t depend on nouns but could move right to verbs when the circumstances were appropriate.3

…

This work from Gellman is a favourite of mine, and is featured in the January 13, 2020 article in Canadian Art Magazine and you’ll find it in the book,

There are more LOoW images embedded in the January 6, 2020 article on the Canadian Art Magazine website.

Derksen and his poem

Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Theodor W. Adorno, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel were unexpected guest stars in Derksen’s essay, “From Two to Another: The Anti-Matter Series,” given that he is an award-winning poet. These days he has this on his profile page on the Department of English, Simon Fraser University website, “Dean and Associate Provost, Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies.”

From LOoW,

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels are well known as materialists, having helped define a materialist view of history, of economics and of capitalism. And both Marx and Engels aimed to develop Marxism as a science rather than a model based on naturalizing capitalism and “man.” … [p. 89]

Derksen includes a diagram/poem, for which I can’t find a digitized copy, but here’s what he had to say about it,

My mode of looking at this [antimatter] is through poetic research —which itself does not aim to arrive at a synthesis but instead looks for relational moments. In this I also see a poetic language emerge from both discourses [artistic/scientific]—matter-antimatter thought and dialectical thinking. For my contribution to Leaning Out of Windows, I have tried to combine the scientific aspect of dialectical thinking with the poetic aspect of matter-antimatter thought and experimentation. To do this, I have taken the diagrammatic rendering of Carl Anderson’s experiment which resulted in his 1932 paper … as a model to relate the dialectical thinking at the heart of Marxism and matter-antimatter thought. …

Towards the end of his essay, Derksen notes that he’s working (on what I would call) a real poem. I sent an email to Derksen on August 21, 2023 asking,

- Have you written the poem or is still in progress?

- If you have written it, has it been published or is it being readied for publication? I would be happy to mention where.

- If you do have it ready and would like to ‘soft launch’ the poem, could you send it to me for inclusion in the post?

No response at this time.

Flashback to Alan Storey

I think it was 2002 or 2003 when I first heard about an artist at TRIUMF, Alan Storey. The ‘residency’ was the product of a joint effort between the Canada Council for the Arts (Canada Council) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada (NSERC).

I spoke with Storey towards the end of his ;residency; and he was a little disappointed because nothing much had come of it. Nobody really seemed to know what to do with an artist at a nuclear facility and he didn’t really didn’t seem to know either. (Alan Storey’s work can be seen in the City of Vancouver’s collection of public art works here and on his website.)

My guess is that someone had a great idea but didn’t think past the ‘let’s give money to science institutions so they can host some artists who will magically produce wonderful things for us’ stage of thinking. While there is no longer a Canada Council/NSERC programme, it’s clear from LOoW (funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada [SSHRC]) that lessons have been learned.

Kudos to David Morissey who acted as an interface and convenor for the artists and to Nigel Smith (Director 2021 – present) and Jonathan Bagger (Director 2014 – 2020) for supporting the project from the TRIUMF side and to Ingrid Koenig and Randy Lee Cutler who organized and facilitated LOoW from the artists’ side.

Now, for the nits

“Co-thought” is mentioned a number of times. What is it? According to my searches, it has something to do with gestures. Here’s one of the few reference I could find for co-thought,

Co-thought and co-speech gestures are generated by the same action generation process by Mingyuan Chu and Sotaro Kita. Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2016 Feb;42(2):257-70. doi: 10.1037/xlm0000168. Epub 2015 Aug 3.

Abstract

People spontaneously gesture when they speak (co-speech gestures) and when they solve problems silently (co-thought gestures) [emphasis mine]. In this study, we first explored the relationship between these 2 types of gestures and found that individuals who produced co-thought gestures more frequently also produced co-speech gestures more frequently (Experiments 1 and 2). This suggests that the 2 types of gestures are generated from the same process. We then investigated whether both types of gestures can be generated from the representational use of the action generation process that also generates purposeful actions that have a direct physical impact on the world, such as manipulating an object or locomotion (the action generation hypothesis). To this end, we examined the effect of object affordances on the production of both types of gestures (Experiments 3 and 4). We found that individuals produced co-thought and co-speech gestures more often when the stimulus objects afforded action (objects with a smooth surface) than when they did not (objects with a spiky surface). These results support the action generation hypothesis for representational gestures. However, our findings are incompatible with the hypothesis that co-speech representational gestures are solely generated from the speech production process (the speech production hypothesis).

It would have been nice if Koenig and Cutler had noted they were borrowing a word ot coining a word and explaining how it was being used in the LOoW context.

Fruit, passports, and fishing trips

The editors/writers use the words or variants, metaphor, poetry, and analogy with great abandon.

“Fruitful bridge” (top of page) and “fruitful match-ups” (bottom of page) on p. 18 seemed a bit excessive as did the “metaphorical passport” on p. 5.

I choked a bit over this on p. 19, “… these artist/scientist interactions can be seen as ‘procedural metaphors’ that enact a thought experiment … .” Procedural metaphor? It seems a bit of a stretch.

A last example and it’s a pair: “metaphorical fishing trips whereby artist and scientists received whatever they might reel in …” on p. 42 (emphases mine). Fishing trips are mentioned in a later essay too, one of the few times there’s some sort of follow through on an analogy.

Maybe someone who wasn’t involved with the project should have taken a look at the text before it was sent to the printer.

Using the words, poetry, metaphor, and analogy can be tricky and, I want to emphasize that in my opinion, those words were not often put to good use in this book.

Moving on, arts and sciences together have a longstanding history.

*ETA October 3, 2023: Ooops! I had a comment about the use of the word ‘passports’ in the book but somewhere in all my edits, I cut it out. (huff)*

Poetry and physics

One of the giants of 19th century physics, James Clerk Maxwell was also known for his poetry. and some of the most evocative (poetic) text in the LOoW book can be found in the quotes from various physicists of the 20th century. The link between physicist and poetry is explicit in a September 17, 2018 posting (12 poignant poems (and one bizarre limerick) written by physicists about physics) by Colin Hunter for the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Canada.

Going back further, there’s De rerum natura, a poem in six books, by Lucretius ((c. 99 BCE– c. 55 BCE). Amongst many other philosophical concerns (e.g., the nature of mind and soul, etc.), Lucretius also discussed atomism (“… a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms; from the Atomism Wikipedia entry). So, poetry and physics have a long history.

Leaving aside Derksen’s diagram/poem, there’s a dearth of poetry in the book except for a suite of seven poems from TRIUMF physicist and professor at UBC, Jess Brewer following his “Emergence, Free Will and Magic” essay,

Emergence / An extremely brief history of one universe, expressed as a series of science fiction poems by Jess H. Brewer, June 29, 2019

Inspired by Dyson Freeman’s delightful lecture series , “Time Without End: Physics and Biology in an Open Universe,” Reviews of Modern Physics (51) 1979

1. Bang

Why not?

For reasons known only to itself,

the universe begins

The quantum foam of spacetime seethes

with effortless energies,

entering and exiting this continuum

with a turbulent intensity

transcending the superficially smooth

expanding cosmos

and yet it kens the glacial passage of “time”,

because it waits.

And kens the vast reaches of “space”,

because it watches,

Its own experiences has taught it that

from each iteration of complexity,

awareness will emerge.… [p. 149]

My thanks to Brewer for the poetry and magic and my apologies for any mistakes I’ve introduced into his piece. I was trying to be especially careful with the punctuation as that can make quite a difference to how a piece is read.

While Muriel Rukeyser is not a physicist at TRIUMF or, indeed, alive, one of her poems leads the essay “Leaning into Language or the Universe is Made of Stories,” by Randy Lee Cutler and Ingrid Koenig,

Time comes into it

Say it. Say it.

The universe is made of stories,

not of atoms..

—Muriel Ruykeyser, Speed of Darkness, 1968

Before getting into the response that physicist, David Morrissey, had to the poem, here’s a little about the poet, from the Poetry Foundation’s Muriel Ruykeyser (1913-1980) webpage,

Muriel Rukeyser was a poet, playwright, biographer, children’s book author, and political activist. Indeed, for Rukeyser, these activities and forms of expression were linked. …

…

One of Rukeyser’s intentions behind writing biographies of nonliterary persons was to find a meeting place between science and poetry. [emphasis mine] In an analysis of Rukeyser’s The Life of Poetry, Virginia Terris argued that Rukeyser believed that in the West, poetry and science are wrongly considered to be in opposition to one another. Thus, writes Terris, “Rukeyser [set] forth her theoretical acceptance of science … [and pointed] out the many parallels between [poetry and science]—unity within themselves, symbolic language, selectivity, the use of the imagination in formulating concepts and in execution. [emphasis mine] Both, she believe[d], ultimately contribute to one another.”

…

Rokeyser’s poem raised a few questions. Is her poem a story? Or, is she using symbolic language, the poem, to poke fun at stories and atoms? Is she suggesting that atoms are really stories? I found the poem evocative especially with where it was placed in the book.

Morrissey takes a prosaic approach, from the essay “Leaning into Language or the Universe is Made of Stories,”

… [in response to Rukeyser’s claim about stories] Morrissey responded stating that “scientific theories are stories—but how we evaluate stories is important—they need to be true, but they do probe, and some are more popular than others, especially theories that we can’t measure.” He surprised us further when he said that wrong stories can also be useful—they may have elements in them that turn out to be useful for future research. … [pp. 205-6]

In general and throughout this project, it seems as if they (artists and physicists) tried but, for the most part, were never quite able to articulate in poetic, metaphoric, and analogical forms. They tended to fall back onto their preferred modes of scientific notations, prosaic language, and artworks.

Both sides of the knife blade cut

Everybody does it. Poets, academics, artists, scientists, etc. we all appropriate ideas and language, sometimes without understanding them very well. Take this for example, from the Canadian Broadcasting’s (CBC) Books “Elementary Particles” August 16, 2023 webpage,

Elementary Particles by Sneha Madhavan-Reese

A poetry collection about family history and scientific exploration

Through keen, quiet observation, Sneha Madhavan-Reese’s evocative new collection takes us from the wide expanse of rural India to the minute map of Michigan we carry on the palms of our hands. These poems contemplate ancestral language, the wonder and uncertainty of scientific discovery, the resilience of a dung beetle, the fleeting existence of frost flowers on the Arctic Ocean.

The collection is full of familiar characters, from Rosa Parks to Seamus Heaney to Corporal Nathan Cirillo, anchoring it in specific moments in time and place, but has the universality that comes from exploring the complex relationship between a child and her immigrant parents, and in turn, a mother and her children. Elementary Particles examines the building blocks of a life — the personal, family, and planetary histories, transformations, and losses we all experience. (From Brick Books)

Sneha Madhavan-Reese is a writer currently based in Ottawa. In 2015 she received Arc Poetry Magazine’s Diana Brebner Prize and was shortlisted for the Montreal International Poetry Prize. Her previous poetry collection is called Observing the Moon

As you can see, there’s no substantive mention of physics in this book description—it’s just a title. Puzzling since there’s this about the author on Asian Heritage Canada’s Sneha Madhavan-Reese webpage

Sneha Madhavan-Reese’s award winning poetry has been widely published in literary magazines in North America and Australia. She earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from MIT in 2000, and a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Michigan in 2002. Madhavan-Reese currently lives in Ottawa, Ontario. [emphases mine]

It seems the mechanical engineer did not write up her book blurb because even though the poet’s scientific specialty is not physics as such, I’d expect a better description.

In the end, it seems art and science or poetry and science (in this case, physics) sells.

Alchemy, beauty, and Marx’s surprise connection to atomism

It was unexpected to see a TRIUMF physicist reference alchemy. The physicists haven’t turned lead into gold but they have changed one element into another. If memory holds it was one metallic atom being changed into another type of metallic atom. (Having had to return the book to the library, memory has serve.)

The few references to alchemy that I’ve stumbled across elsewhere in my readings of assorted science topics are derogatory, hence the surprise. Things may be changing; Princeton University Press published a November 7, 2018 posting by author William R. Newman about Newton and alchemy. First, here’s a bit about William Newman,

William R. Newman is Distinguished Professor and Ruth N. Halls Professor in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science and Medicine at Indiana University. His many books include Atoms and Alchemy: Chymistry and the Experimental Origins of the Scientific Revolution and Promethean Ambitions: Alchemy and the Quest to Perfect Nature. He lives in Bloomington, Indiana.

Now for Newman’s comments, from the November 7, 2018 posting,

People often say that Isaac Newton was not only a great physicist, but also an alchemist. This seems astonishing, given his huge role in the development of science. Is it true, and if so, what is the evidence for it?

WN: The astonishment that Newton was an alchemist stems mostly from the derisive opinion that many moderns hold of alchemy [emphasis mine]. How could the man who discovered the law of universal gravitation, who co-invented calculus, and who was the first to realize the compound nature of white light also engage in the seeming pseudo-science of alchemy? There are many ways to answer this question, but the first thing is to consider the evidence of Newton’s alchemical undertaking. We now know that at least a million words in Newton’s hand survive in which he addresses alchemical themes. Much of this material has been edited in the last decade, and is available on the Chymistry of Isaac Newton site at www.chymistry.org. Newton wrote synopses of alchemical texts, analyzed their content in the form of reading notes and commentaries, composed florilegia or anthologies made up of snippets from his sources, kept experimental laboratory notebooks that recorded his alchemical research over a period of decades, and even put together a succession of concordances called the Index chemicus in which he compared the sayings of different authors to one another. The extent of his dedication to alchemy was almost unprecedented. Newton was not just an alchemist, he was an alchemist’s alchemist.

…

Beauty

The ‘beauty’ essay by Ingrid Koenig was also a surprise. Beauty seems to be anathema to contemporary artists. I wrote this in an August 23, 2016 posting (Georgina Lohan, Bharti Kher, and Pablo Picasso: the beauty and the beastliness of art [in Vancouver]), “It seems when it comes to contemporary art, beauty is transgressive.”

Koenig describes it as irrelevant for contemporary artists and yet, beauty is an important attribute to physicists. Her thoughts on beauty in visual art and in physics were a welcome addition to the book.

Marx’s connection to atomism

This will take a minute.

De rerum natura, a six-volume poem by Lucretius (mentioned under the Poetry and physics subhead of this posting), helped to establish the concept of atomism. As it turns out, Lucretius got the idea from earlier thinkers, Epicurus and Democritus.

Karl Marx’s doctoral dissertation, which focused on Lucretius, Epicurus and more, suggests an interest in science that may have led to his desire to establish economics as a science. From Cambridge University Press’s “Approaches to Lucretius; Traditions and Innovations in Reading the De Rerum Natura,” Chapter 12 – A Tribute to a Hero: Marx’s Interpretation of Epicurus in his Dissertation,

Summary

This chapter turns to Karl Marx’s treatment of Epicureanism and Lucretius [emphasis mine] in his doctoral dissertation, and argues that the questions raised by Marx may be brought to bear on our own understanding of Epicurean philosophy, particularly in respect of a tension between determinism and individual self-consciousness in a universe governed by material causation. Following the contours of Marx’s dissertation [emphasis mine], the chapter focusses on three key topics: the difference between Democritus’ and Epicurus’ methods of philosophy; the swerve of the atom; and the so-called ‘meteors’, or heavenly bodies [emphasis mine]. Marx sought to develop Hegel’s understanding of Epicurus, in particular by elevating the principle of autonomous action to a first form of self-consciousness – a consideration largely mediated by Lucretius’ theorization of the atomic swerve and his poem’s overarching framework of liberating humans from the oppression of the gods.

Fascinating, eh? The rest of this is behind a paywall. For the interested, here’s a citation and link for the book,

Approaches to Lucretius; Traditions and Innovations in Reading the De Rerum Natura

Edited by Donncha O’Rourke, University of EdinburghPublisher: Cambridge University Press

Online publication date: June 2020

Print publication year: 2020

Online ISBN: 9781108379854DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108379854

32.99 (USD) Digital access

It’s a little surprising Derksen doesn’t mention the connection in his essay.

Finally

It’s an interesting book if not an easy one. (By the way, I wish they’d included an index.) You can get a preview of some of the artwork in the January 6, 2020 article on the Canadian Art Magazine website.

I can’t rid myself of the feeling that LOoW (the book) is meant to function as a ‘proof of concept’ for someone wanting to start an art/science department or programme at the Emily Carr University of Art + Design, perhaps jointly with the University of British Columbia. It is highly unusual to see this sort of material in anything other than a research journal or as a final summary to the granting agency.

Should starting an art/science programme be the intention, I hope they are successful in getting such it together and, in the meantime, thank you to the physicists and artists for their work.

We should all ‘lean out of windows’ on occasion and, if it means, falling or encountering ‘dangerous, uncomfortable ideas’ then, that’s alright too.