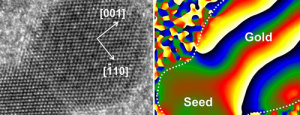

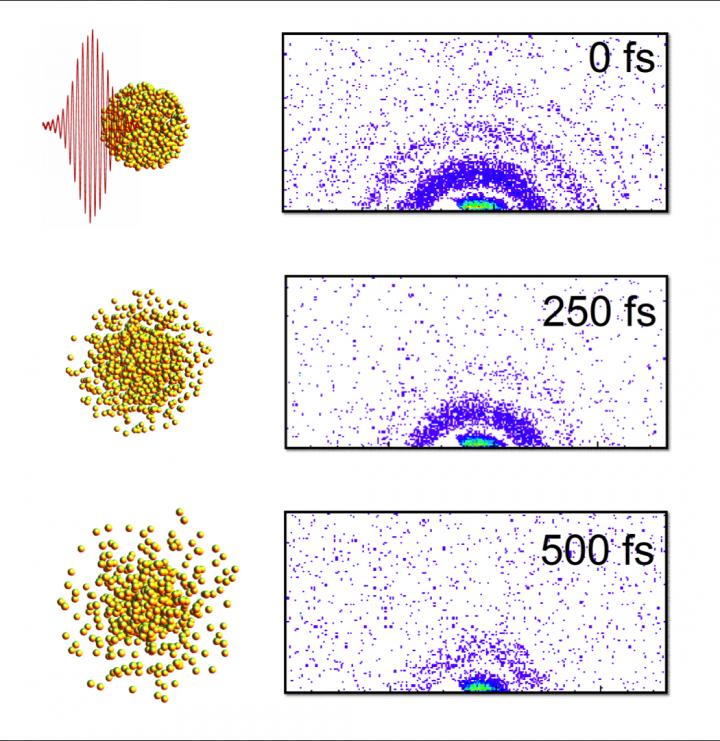

Caption: Here are “stills” from an X-ray “movie” of an exploding nanoparticle. The nanoparticle is superheated with an intense optical pulse and subsequently explodes (left). A series of ultrafast x-ray diffraction images (right) maps the process and contains information how the explosion starts with surface softening and proceeds from the outside in. Credit: Christoph Bostedt

A Feb. 10, 2016 news item on Nanotechnology Now provides more information about the ‘snapshots,

Just as a photographer needs a camera with a split-second shutter speed to capture rapid motion, scientists looking at the behavior of tiny materials need special instruments with the capacity to see changes that happen in the blink of an eye.

An international team of researchers led by X-ray scientist Christoph Bostedt of the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory and Tais Gorkhover of DOE’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory used two special lasers to observe the dynamics of a small sample of xenon as it was heated to a plasma.

A Feb. 10, 2016 Argonne National Laboratory news release (also on EurekAlert) by Jared Sagoff, which originated the news item, provides more technical details,

Bostedt and Gorkhover were able to use the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at SLAC to make observations of the sample in time steps of approximately a hundred femtoseconds – a femtosecond being one millionth of a billionth of a second [emphasis mine]. The exposure time of the individual images was so short that the quickly moving particles in the gas phase appeared frozen. “The advantage of a machine like the LCLS is that it gives us the equivalent of high-speed flash photography as opposed to a pinhole camera,” Bostedt said. The LCLS is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

The researchers used an optical laser to heat the sample cluster and an X-ray laser to probe the dynamics of the cluster as it changed over time. As the laser heated the cluster, the photons freed electrons initially bound to the atoms; however, these electrons still remained loosely bound to the cluster.

By imaging exploding nanoparticles, the team was able to make measurements of how they change over time in extreme environments. “Ultimately, we want to understand how the energy from the light affects the system,” Gorkhover said.

“There are really no other techniques that give us this good a resolution in both time and space simultaneously,” she added. “Other methods require us to take averages over many different ‘exposures,’ which can obscure relevant details. Additionally, techniques like electron microscopy involve a substrate material that can interfere with the behavior of the sample.”

According to Bostedt, the research could also impact the study of aerosols in the environment or in combustion, as the dual-laser “pump and probe” model could be adapted to study materials in the gas phase. “Although our material goes from solid to plasma very quickly, there are other types of materials you could study with this or a similar technique,” he said.

I marvel at how very brief the time intervals are at the femtoscale and for that matter, the other subatomic scales.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Femtosecond and nanometre visualization of structural dynamics in superheated nanoparticles by Tais Gorkhover, Sebastian Schorb, Ryan Coffee, Marcus Adolph, Lutz Foucar, Daniela Rupp, Andrew Aquila, John D. Bozek, Sascha W. Epp, Benjamin Erk, Lars Gumprecht, Lotte Holmegaard, Andreas Hartmann, Robert Hartmann, Günter Hauser, Peter Holl, Andre Hömke, Per Johnsson, Nils Kimmel, Kai-Uwe Kühnel, Marc Messerschmidt, Christian Reich, Arnaud Rouzée, Benedikt Rudek, Carlo Schmidt et al. Nature Photonics 10, 93–97 (2016) doi:10.1038/nphoton.2015.264 Published online 25 January 2016

This paper is behind a paywall.