Structural colour due to nanoscale structures such as those found on Morpho butterfly wings, jewel beetles, opals, and elsewhere is fascinating to me (Feb. 7, 2013 posting). It would seem many scientists share my fascination including these groups at the UK’s University of Cambridge and Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute, from the May 30, 2013 University of Cambridge news release (also on EurekAlert),

Instead of through pigments, these ‘polymer opals’ get their colour from their internal structure alone, resulting in pure colour which does not run or fade. The materials could be used to replace the toxic dyes used in the textile industry, or as a security application, making banknotes harder to forge. Additionally, the thin, flexible material changes colour when force is exerted on it, which could have potential use in sensing applications by indicating the amount of strain placed on the material.

The most intense colours in nature – such as those in butterfly wings, peacock feathers and opals – result from structural colour. While most of nature gets its colour through pigments, items displaying structural colour reflect light very strongly at certain wavelengths, resulting in colours which do not fade over time.

In collaboration with the DKI (now Fraunhofer Institute for Structural Durability and System Reliability) in Germany, researchers from the University of Cambridge have developed a synthetic material which has the same intensity of colour as a hard opal, but in a thin, flexible film.

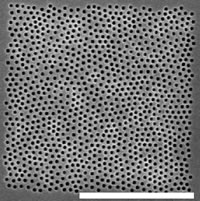

Here’s what the researchers’ synthetic opal looks like,

![Polymer Opals Credit: Nick Saffel [downloaded from http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/flexible-opals]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/FlexibleOpal-300x146.jpg)

Polymer Opals Credit: Nick Saffel [downloaded from http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/flexible-opals]

Naturally-occurring opals are formed of silica spheres suspended in water. As the water evaporates, the spheres settle into layers, resulting in a hard, shiny stone. The polymer opals are formed using a similar principle, but instead of silica, they are constructed of spherical nanoparticles bonded to a rubber-like outer shell. When the nanoparticles are bent around a curve, they are pushed into the correct position to make structural colour possible. The shell material forms an elastic matrix and the hard spheres become ordered into a durable, impact-resistant photonic crystal.

“Unlike natural opals, which appear multi-coloured as a result of silica spheres not settling in identical layers, the polymer opals consist of one preferred layer structure and so have a uniform colour,” said Professor Jeremy Baumberg of the Nanophotonics Group at the University’s Cavendish Laboratory, who is leading the development of the material.

Like natural opals, the internal structure of polymer opals causes diffraction of light, resulting in strong structural colour. The exact colour of the material is determined by the size of the spheres. And since the material has a rubbery consistency, when it is twisted and stretched, the spacing between spheres changes, changing the colour of the material. When stretched, the material shifts into the blue range of the spectrum, and when compressed, the colour shifts towards red. When released, the material will return to its original colour.

I find the potential for use in the textile industry a little more interesting than the anti-counterfeiting application. (There’s a Canadian company, Nanotech Security Corp., a spinoff from Simon Fraser University, which capitalizes on the Blue Morpho butterfly wing’s nanoscale structures for an anti-counterfeiting application as per my first posting about the company on Jan. 17, 2011.) There has been at least one other attempt to create a textile that exploits structural colour. Unfortunately Teijin Fibres has stopped production of its morphotex, as per my April 12, 2012 posting.

Here’s what the news release has to say about textiles and the potential importance of structural colour,

The technology could also have important uses in the textile industry. “The World Bank estimates that between 17 and 20 per cent of industrial waste water comes from the textile industry, which uses highly toxic chemicals to produce colour,” said Professor Baumberg. “So other avenues to make colour is something worth exploring.” The polymer opals can be bonded to a polyurethane layer and then onto any fabric. The material can be cut, laminated, welded, stitched, etched, embossed and perforated.

The researchers have recently developed a new method of constructing the material, which offers localised control and potentially different colours in the same material by creating the structure only over defined areas. In the new work, electric fields in a print head are used to line the nanoparticles up forming the opal, and are fixed in position with UV light. The researchers have shown that different colours can be printed from a single ink by changing this electric field strength to change the lattice spacing.

As for wanting to take this research to market, from the news release,

Cambridge Enterprise, the University’s commercialisation arm, is currently looking for a manufacturing partner to further develop the technology and take polymer opal films to market.

For more information, please contact sarah.collins@admin.cam.ac.uk.

The reference to opals reminded me of yet another Canadian company exploring the uses of structural colour, Opalux, as per my Jan. 31, 2011 posting.