It has to be disconcerting to realize that your precious paintings are deteriorating day by day. In a June 22, 2017 posting titled ‘Art masterpieces are turning into soap‘,

This piece of research has made a winding trek through the online science world. First it was featured in an April 20, 2017 American Chemical Society news release on EurekAlert,

A good art dealer can really clean up in today’s market, but not when some weird chemistry wreaks havoc on masterpieces [emphasis mine]. Art conservators started to notice microscopic pockmarks forming on the surfaces of treasured oil paintings that cause the images to look hazy. It turns out the marks are eruptions of paint caused, weirdly, by soap that forms via chemical reactions. Since you have no time to watch paint dry, we explain how paintings from Rembrandts to O’Keefes are threatened by their own compositions — and we don’t mean the imagery.

Here’s the video,

…

Now, for the latest: canavases are deteriorating too. A May 23, 2018 news item on Nanowerk announces the latest research on the ‘canvas issue’ (Note: A link has been removed),

Paintings by Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso and Johannes Vermeer have been delighting art lovers for years. But it turns out that these works of art might be their own worst enemy — the canvases they were painted on can deteriorate over time.

In an effort to combat this aging process, one group is reporting in ACS Applied Nano Materials (“Combined Nanocellulose/Nanosilica Approach for Multiscale Consolidation of Painting Canvases”) that nanomaterials can provide multiple layers of reinforcement.

A May 23, 2018 American Chemical Society (ACS) news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

One of the most important parts of a painting is the canvas, which is usually made from cellulose-based fibers. Over time, the canvas ages, resulting in discoloration, wrinkles, tears and moisture retention, all greatly affecting the artwork. To combat aging, painting conservators currently place a layer of adhesive and a lining on the back of a painting, but this treatment is invasive and difficult to reverse. In previous work, Romain Bordes and colleagues from Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, investigated nanocellulose as a new way to strengthen painting canvases on their surfaces. In addition, together with Krzysztof Kolman, they showed that silica nanoparticles can strengthen individual paper and cotton fibers. So, they next wanted to combine these two methods to see if they could further strengthen aging canvas.

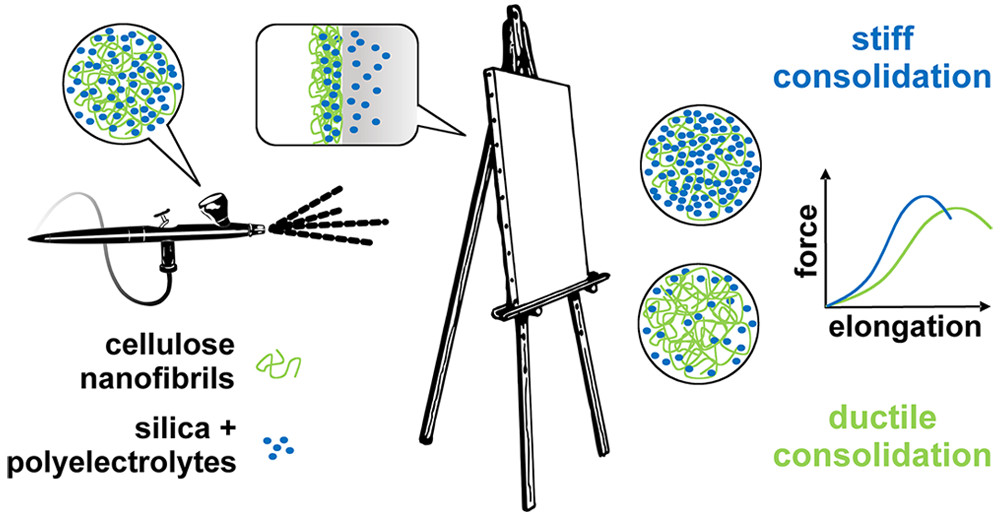

The team combined polyelectrolyte-treated silica nanoparticles (SNP) with cellulose nanofibrils (CNF) for a one-step treatment. The researchers first treated canvases with acid and oxidizing conditions to simulate aging. When they applied the SNP-CNF treatment, the SNP penetrated and strengthened the individual fibers of the canvas, making it stiffer compared to untreated materials. The CNF strengthened the surface of the canvas and increased the canvas’s flexibility. The team notes that this treatment could be a good alternative to conventional methods.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Combined Nanocellulose/Nanosilica Approach for Multiscale Consolidation of Painting Canvases by Krzysztof Kolman, Oleksandr Nechyporchuk, Michael Persson, Krister Holmberg, and Romain Bordes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater., Article ASAP DOI: 10.1021/acsanm.8b00262 Publication Date (Web): April 26, 2018

Copyright © 2018 American Chemical Society

This image illustrating the researchers’ solution accompanies the article,

Courtesy: ACS

The European Union’s NanoRestART project was mentioned here before they’d put together this introductory video, which provides a good overview of the research,

For more details about the problems with contemporary and modern art, there’s my April 4, 2016 posting when the NanoRestART project was first mentioned here and there’s my Jan. 10, 2017 posting which details research into 3D-printed art and some of the questions raised by the use of 3D printing and other emerging technologies in the field of contemporary art.

Johannes Vermeer, View of Delft, c. 1660 – 1661 (Mauritshuis, The Hague)

Johannes Vermeer, View of Delft, c. 1660 – 1661 (Mauritshuis, The Hague) ‘Sand grains’ In the red tiles of ‘View of Delft’ by Johannes Vermeer shows ‘lead soap spheres’ (Annelies van Loon, UvA/Mauritshuis)

‘Sand grains’ In the red tiles of ‘View of Delft’ by Johannes Vermeer shows ‘lead soap spheres’ (Annelies van Loon, UvA/Mauritshuis)